Shapoval Yu.V.

Religious values: religious analysis (on the example of Judaism, Christianity, Islam)

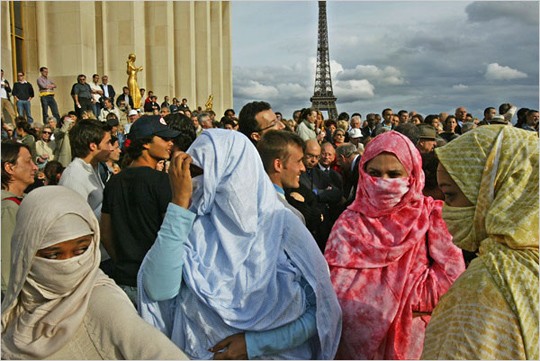

In modern secular society, the dominant trend in relation to religious values has been their erosion and misunderstanding of their essence. The processes of profanization, ethicization, politicization and commercialization of religion are projected onto religious values, which are reduced to ethical standards of behavior, equated to universal human values, and in the worst case, become a means in a political game or an instrument of material enrichment. The manipulation of religious values for one’s own purposes has become a widespread phenomenon, as we see in the example extremist organizations using religious slogans, or pseudo-religious organizations that, under the guise of religious values, pursue commercial goals. The postmodern game, which breaks signifier and signified, form and content, appearance and essence, has also drawn religious values into its whirlpool, which become a convenient form for completely non-religious content. Therefore, an adequate definition of religious values, which would make it possible to distinguish them from a pseudo-religious surrogate, is of particular relevance and significance today. Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to identify the essence and content of religious values, without which it is impossible to raise the question of their dialogue with secular values.

To achieve this goal, it is important to choose an adequate research path. The logic of our research involves revealing the following aspects. Firstly, it is necessary to identify the main formative principle of religious values, which constitutes them and distinguishes them from other values. This principle will be the criterion of value position in the religious sphere. Of course, this essential principle will also give direction to our research. Secondly, the values we are considering are religious, therefore, they should be studied in the context of religion, and not in isolation from it. In our opinion, the reason for the vagueness and uncertainty of the very concept of religious values seems to be the desire to explore their essence and content not in a religious context, but in any other context: political, psychological, social, cultural. Thirdly, a more holistic view of religious values, and not simply listing them, is provided, in our opinion, by a religious picture of the world, which, of course, is value-based.

The essential feature of religious values is, first of all, their ontology. This was very well revealed in his concept by P. Sorokin, characterizing an ideational culture with the religious values fundamental to it. According to him, “1) reality is understood as a non-perceptible, immaterial, imperishable Being; 2) goals and needs are mainly spiritual; 3) the degree of their satisfaction is maximum and at the highest level; 4) the way to satisfy or realize them is the voluntary minimization of most physical needs...” M. Heidegger also notes the existentiality of religious values, saying that after their overthrow in Western culture, the truth of being became impenetrable, and metaphysics was replaced by the philosophy of subjectivity. The principle of Being, as opposed to changeable becoming, is fundamental to religious values. The principle of Being in religion is expressed in the existence of God, who is transcendent, unchanging, eternal, all being is derived from it and is supported by it. This is especially clearly expressed in revealed religions, which are based on Revelation, in which God reveals himself to people and, with his signs, commandments, and messages from top to bottom, orders all existence, including the natural world, human society, and the life of every person. In Christianity God says “Let there be”, in Islam “Be!” and the world is brought into existence.

The principle of Being as eternal and unchanging is manifested in that deep connection between word and being, which is characteristic of religion. The fundamental role of the Word in the creation of being is indicated by the Holy Scriptures. The Gospel of John begins with the words: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1). In the Koran: “He is the One who created the heavens and the earth for the sake of truth. On that day He will say: “Be!” - and it will come true. His Word is the truth...” (Quran 6, 73). God is the Word and is the Truth is indicated in the sacred books. Thus, the Word ascends to God and produces the truth of being. Consequently, naming things is revealing the truth of their existence or indicating this truth.

In this context, it is interesting to turn to the Father of the Church - Gregory of Nyssa, who in his short work “On what the name and title “Christian” means” affirms the fundamentality of the principle of Being for a religious person. To bear the name “Christian” means to be a Christian, and to be a Christian necessarily involves “imitation of the Divine nature.” God is separated from man and the nature of God is inaccessible to human knowledge, but the names of Christ reveal the image of perfect existence that must be followed. Saint Gregory cites such names of Christ as wisdom, truth, goodness, salvation, strength, firmness, peace, purification and others. The logic of the holy father is as follows: if Christ is also called a stone, then this name requires from us firmness in a virtuous life.

In Islam we also find a provision about the 99 names of Allah, which he revealed to humanity: “Allah has the most wonderful names. Therefore, call upon Him through them and leave those who deviate from the truth regarding His names" (Quran 7, 180). For a Muslim, it is necessary that “he has true faith in Allah, maintains a strong connection with Him, constantly remembers Him and trusts in Him...”. All suras of the Koran, except one, and the words of a Muslim begin with the “remembrance” of the name of Allah - “In the name of Allah, the Gracious and the Merciful.” Hence, the special position of the Koran, which is the word of Allah given in revelation to the Prophet Muhammad. The deepest connection between name and being was studied and revealed in their works by Russian thinkers, name-glorifiers P.A. Florensky, father Sergius Bulgakov, A.F. Losev. Even the representative of postmodernism, J. Derrida, turns to this topic at the end of his life in connection with the search for traces of Being in the world.

Thus, the names of God indicate the truth of existence and, accordingly, religious values. God is truth, goodness, beauty, wisdom, strength, love, light, life, salvation. Everything that is part of God is valuable and must be imitated.

P. Sorokin, in addition to the principle of Being for religious values, points to the priority of the spiritual. Indeed, especially in revealed religions, divine existence does not merge with the sensory, earthly world, but is supersensible, transcendental, spiritual. Consequently, religious values presuppose a certain structure of existence, namely a metaphysical picture of the world, in which there is a sensory and supersensible world, which is the beginning, foundation and end of the first. In religion, a hierarchy of the world is built in which the higher spiritual layers are subordinated to the lower material layers. Hierarchy is a stepwise structure of the world, determined by the degree of closeness to God. Dionysius the Areopagite in his work Corpus Areopagiticum vividly describes this ladder principle of the structure of the world. The goal of the hierarchy is “possible assimilation to God and union with Him.” The love of God for the created world and the love of the world for its Creator, striving for the unity of all being in God, is the basis of order and order, hierarchy. Love, which connects and unites the world and God, appears in Dionysius, as in Gregory of Nyssa, as a fundamental ontological principle and, accordingly, the highest value. The principle of hierarchy is refracted in the structure of man as a bodily-mental-spiritual being, in which the strict subordination of the lower layers to the higher spiritual levels must be observed. Moreover, hierarchy permeates both the church organization and the heavenly world itself.

Thus, the principle of Being is the formative element of religious values, since here we come from God (the fullness of being) to values, and not vice versa. Therefore, religious values rooted in the divine eternal, unchanging and incorruptible being are absolute, eternal and incorruptible. In a situation with “local values”, in which values lose their ontological basis, it is not being that gives value, but values that are superimposed on being, being begins to be assessed by certain criteria: the interests and needs of the subject, national interests, the interests of all humanity and other interests. Of course, all of these interests are constantly changing; accordingly, “local values” cannot be designated as eternal and unchanging.

To adequately understand religious values, one must turn to religion itself, since all other contexts are external to them. Unfortunately, in modern humanities, an eclectic approach to religious values has become widespread, according to which an arbitrary selection of them is made and further adaptation to political or any other goals. The path of eclecticism is a very dangerous path, since it leads, for example, to such formations as “political Islam.” We are increasingly striving to adapt religion and religious values to the needs of modern man and society, forgetting that, in fact, these values are eternal, and our needs are changeable and transitory. Accordingly, human needs should have such an absolute reference point as religious values, and not vice versa.

Based on this, religious values must first be considered on their “internal territory” (M. Bakhtin), that is, in religion, in order to determine the unchangeable core of the religious tradition, values, and areas where points of contact are possible, even dialogue with secular values.

Religion appears as a person’s relationship with God, who is the Creator and support of the world. First of all, we note that a religious attitude is essential for a person in the sense that it expresses “the primordial yearning of the spirit, the desire to comprehend the incomprehensible, to express the inexpressible, the thirst for the Infinite, the love of God.” In this context, religion appears as a phenomenon deeply inherent in man and, therefore, religion will exist as long as man exists. Based on this, the attempts of positivists, in particular O. Comte, to define religion as a certain theological stage of human development, which will be replaced by a positivist stage, seem unjustified. Also unconvincing today is the point of view of S. Freud, who considered religion to be a manifestation of infantilism, a stage of childhood development of humanity, which will be overcome in the future. Our position is close to the point of view of K.G. Jung, for whom religion is rooted in the archetypal unconscious layer of the human psyche, that is, deeply inherent in man.

The religious attitude becomes clearer if we go from the word “religare” itself, which means to bind, connect. In this context, V. Soloviev understands religion: “Religion is the connection between man and the world with the unconditional beginning and focus of all things.” The meaning and purpose of any religion is the desire for unity with God.

The religious unity of a person with God requires a free search on the part of a person, which presupposes aspiration and turning towards the object of his faith. In religion, the entire spiritual-mental-physical being of a person is turned towards God. This is expressed in the phenomenon of faith. Faith is a state of extreme interest, capture by the ultimate, infinite, unconditional; it is based on the experience of the sacred in the finite. Accordingly, fundamental to religion is the religious experience in which a person experiences God as Presence (M. Buber), as spiritual evidence (I.A. Ilyin). In this sense, the definition of P.A. is very accurate. Florensky: “Religion is our life in God and God in us.”

Living religious experience is personal, in which a person stands alone before God and bears personal responsibility for his decisions and deeds, for his faith as a whole. S. Kierkegaard pointed out that in religious terms a person is important as a unique and inimitable existence, a person as such, and not in his social dimensions. The next important feature of religious experience is the involvement of the whole human being in it. I.A. Ilyin, who was engaged in the study of religious experience, notes: “But it is not enough to see and perceive the divine Object: one must accept It with the last depths of the heart, involve in this acceptance the power of consciousness, will and reason and give this experience fateful power and significance in personal life.” Religious experience is the ontology of human development, since it requires “spiritual self-construction” from him. Religion completely transforms a person; moreover, the old person dies in order for a renewed person to be born - “a new spiritual personality in man.” The main distinguishing feature of this personality is the “organic integrity of the spirit,” which overcomes the internal gaps and splits of faith and reason, heart and mind, intellect and contemplation, heart and will, will and conscience, faith and deeds, and many others. Religious experience brings order to the chaos of a person’s inner world and builds a hierarchy of the human being. At the head of this hierarchy is the human spirit, to which all other levels are subordinate. A religious person is a whole person who has achieved “inner unity and unity” of all the components of the human being.

If we summarize numerous psychological studies of transpersonal experiences in religious experience, we can say that here the deep layers of the human being are actualized, leading him beyond the limited self-consciousness of the Self to an all-encompassing being. K. G. Jung designates these layers with the concept “archetypal,” and S.L. Frank – “We” layer. Man masters his instinctive unconscious nature, which is gradually permeated by the spirit and submits to it. The spiritual center becomes decisive and directing. Therefore, “religion as the reunification of man with God, as the sphere of human development towards God, is the true sphere of spiritual development.”

Spiritual strength, spiritual activity and spiritual responsibility become characteristics of human existence. Religion is a great claim to Truth, but also a great responsibility. I.A. Ilyin writes: “This claim obliges; it obliges even more than any other claim.” This is a responsibility to oneself, since religious faith determines a person’s entire life and, ultimately, his salvation or destruction. This is responsibility before God: “The believer is responsible before God for what he believes in his heart, what he confesses with his lips and what he does with his deeds.” Religious faith makes a person responsible to all other people for the authenticity and sincerity of his faith, for the substantive thoroughness of his faith, for the deeds of his faith. Therefore, a religious attitude is a responsible, obligatory act.

Of course, as shown above, religious experience represents the foundation of religion as a person’s relationship with God. However, religious experience, profound and practically inexpressible, must be guided by dogmas approved by the Church, otherwise it would be devoid of reliability and objectivity, would be “a mixture of true and false, real and illusory, it would be “mysticism” in the bad sense of the word.” For modern secular consciousness, dogmas appear as something abstract, and dogmatic differences between religions as something insignificant and easily overcome. In fact, for religion itself, dogmas are the expression and defense of revealed truth. It is dogmas that protect the core of faith, outline the circle of faith, the internal territory of religion. Dogmatic statements crystallized, as a rule, in a complex, sometimes dramatic struggle with various kinds of heresies, and represent “a generally valid definition of Truth by the Church.” Dogmas contain an indication of the true path and methods of unity of man with God in a given religion. Based on this, a dogmatic concession, and even more so a refusal of dogma for religion, is a betrayal of faith, a betrayal of the Truth, which destroys religion from the inside.

Unlike personal religious experience, dogmatic definitions are an area of common faith preserved by the Church. Only a single Church can preserve the fullness of the Truth; only “the entire “church people” are able to immaculately preserve and implement, i.e. and reveal this Truth."

V.N. Lossky in his works emphasized the deep connection that exists between religious experience and the dogmas developed and preserved by dogmatic theology. He writes: “Nevertheless, spiritual life and dogma, mysticism and theology are inseparably linked in the life of the Church.” If this connection weakens or breaks, then the foundations of religion are undermined.

However, it may be objected that in such revealed religions as Judaism and Islam there is no dogma and church organization as in Christianity. Indeed, there is no dogma as a principle of faith approved by the institutional structures of the Church, in particular, Ecumenical or local Councils, in Judaism and Islam. Moreover, membership in the Jewish community does not depend on the acceptance of dogmatic tenets, but by birth. Often in the works of Western scholars comparing the Abrahamic religions, Judaism and Islam are presented as religions in which not orthodoxy, as in Christianity, dominates, but orthopraxy, that is, behavior and correct observance of rituals. Western researcher B. Louis writes: “The truth of Islam is determined not so much by orthodoxy, but by orthopraxy. What matters is what a Muslim does, not what he believes." In Judaism, priority is also given to human behavior and the fulfillment of God's Commandments.

Despite all of the above, in Judaism and Islam there are theological definitions that express the principles of faith, developed by the most authoritative people in the field of religion. The medieval Jewish thinker Maimonides formulated thirteen principles of faith, another medieval rabbi Yosef Albo reduced them to three: faith in God, in the divinity of the Torah, in rewards and punishments. In Islam, such definitions, which form the foundation of faith, are tawhid (monotheism) and the five pillars of Islam. In addition, in Judaism there is a rabbinic tradition that deals with theological issues, and in Islam there is kalam and Islamic philosophy. Since the middle of the 8th century, various ideological currents of Islam - Sunnis, Shiites, Kharijites, Mu'tazilites, Murjiites - have been discussing issues of doctrine. First, this is a question of power, then directly problems of faith, then the problem of predestination and controversy over the essence of God and his attributes. A detailed picture of these disputes was presented in their works by Kazakh researchers of Islamic culture and philosophy G.G. Solovyova, G.K. Kurmangalieva, N.L. Seytakhmetova, M.S. Burabaev and others. They showed, using the example of al-Farabi, that medieval Islamic philosophy “expresses Islamic monotheistic religiosity...” and rationally substantiates the Quranic provisions on the unity and uniqueness of God. Thus, Judaism and Islam also contain pillars of faith that express and protect its fundamental principles.

Thus, religion as a person’s relationship with God and the desire for unity with Him presupposes a deep connection between religious experience and dogmatic definitions preserved by the religious community. In unity with religious experience, dogma, an important role in a person’s communication with God belongs to a religious cult, including worship, sacraments, fasts, religious holidays, rituals, and prayers. Religious cult is essentially symbolic, that is, it contains a combination of an external visible symbol with an internal spiritual grace, pointing to divine reality. Thanks to this symbolism, religious actions unite the heavenly and earthly worlds, through which the religious community becomes involved in God. Without exaggeration, we can say that in a religious cult there is a meeting of heaven and earth. Therefore, one cannot talk about a religious cult, about religious rituals as something external and insignificant for faith, since through it the invisible world becomes present for believers in earthly reality. Accordingly, for the Abrahamic religions, religious cult is of fundamental importance. For example, as the Orthodox theologian Bishop Kallistos (Ware) of Diokleia points out: “The Orthodox approach to religion is essentially a liturgical approach: it implies the inclusion of religious doctrine in the context of worship.” In Islam, five-fold prayer, prayer is one of the pillars of faith, as Muhammad Ali Al-Hashimi writes, “prayer is the support of religion, and he who strengthens this support strengthens the religion itself, but he who abandons it destroys this religion.”

So, religious experience, dogma and religious cult represent the “internal territory” of faith, its fundamental foundations, the rejection of which is tantamount to a rejection of faith. It is important to note that the spiritual development of a person, moral values, the moral dimension that we find in religion and to which secular society turns today are the spiritual fruits of this core of religion. As Kazakh researcher A.G. emphasizes. Kosichenko “spiritual development is placed in the confession in the context of the essence of faith...”.

Modern secular humanities, even religious studies, when studying spiritual and moral values rooted in religion, consider cultural-historical, sociocultural, socio-political, ethnic aspects, but not religion itself. This methodological approach leads to a distorted picture, according to which individual ideas and values can be taken out of the religious context and transferred to another sphere, other contexts. For example, medieval Islamic philosophy in Soviet science was studied outside of Islamic doctrine, with emphasis placed on non-religious factors. At the present stage, scientists need to turn to the position of theologians and religious philosophers, which was very well expressed by V.N. Lossky: “We could never understand the spiritual aspect of any life if we did not take into account the dogmatic teaching that lies at its basis. One must accept things as they are, and not try to explain the difference in spiritual life in the West and the East by reasons of an ethnic or cultural nature, when we are talking about the most important reason - the dogmatic difference.” We have given a detailed quotation in order to emphasize that a methodological approach is needed that, when studying religious phenomena, would take into account religion itself, its essential foundations, and not explain religion based on non-religious factors, which also need to be taken into account, but not given priority. No constructive dialogue between secular values and religious values can take place until religion is considered as a holistic phenomenon in the unity of all its aspects: religious experience, dogma, cult, religious ethics and axiology.

Thus, religious values are rooted in religion and it is impossible to reduce them to secular ethics, since outside of man’s relationship with God, ethics loses the absolute criterion of good and evil, which is God and always remains at risk of relativization. As we indicated, all other criteria are relative, since they do not ascend to the eternal, unchanging Being, but descend to the formation of being, constantly changing.

The fundamental religious value, arising from the very understanding of religion as a person’s desire for unity with God, is love. The love of the created world for God and God for the world is the source of all other religious values. Love for one's neighbor, goodness, truth, wisdom, mercy, compassion, generosity, justice and others are derived from this highest value. In the religions of revelation, love acts as an ontological principle leading to the unity of all existence, love is also the main epistemological principle, since God is revealed only to the gaze that loves Him, love also appears as a great ethical principle. In Judaism, one of the fundamental concepts is the agave as God's love for man. This love is understood in three terms. Chesed as the ontological love of the Creator for His creation. Rachamim as the moral love of the Father for his children. Tzedek as the desire to earn God’s love and find deserved love. In Christianity, love as agape characterizes God himself. Here are the famous words of the Apostle John: “Beloved! Let us love one another, because love is from God and everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. He who does not love does not know God, because God is love” (1 John 4:7,8). And in Islam, within the framework of Sufism, love in the three indicated aspects is a fundamental concept, and the Sufis themselves, according to the vivid statement of the Sufi poet Navoi: “They can be called lovers of God and beloved of Him, they can be considered desiring the Lord and desired by Him.”

Striving to become like God, a person makes love the organizing principle of his life as a whole, in all its aspects, including social. Church Father John Chrysostom writes: “We can become like God if we love everyone, even our enemies... If we love Christ, we will not do anything that can offend Him, but we will prove our love by deeds.” This aspect was noticed by M. Weber in his sociology of religion, when he showed the interconnection of religious ethics concerned with salvation human soul and human social practice. He comes to the conclusion: “The rational elements of religion, its “teaching” - the Indian doctrine of karma, the Calvinist belief in predestination, Lutheran justification by faith, the Catholic doctrine of the sacraments - have an internal pattern, and stemming from the nature of ideas about God and the “picture of the world” The rational religious pragmatics of salvation leads, under certain circumstances, to far-reaching consequences in the formation of practical life behavior.” We have given this long quotation because it contains an indication of the sphere in which religion and religious values come into contact with the social world, with secular values. This is an area of social ethics, the formation of which is or may be influenced by religious values. For religion, socio-ethical contexts represent an external boundary, peripheral compared to the “inner territory”. However, life in the world in accordance with religious values is significant for the salvation of a person’s soul, and, consequently, for religion. Accordingly, we can talk about the economic ethics of religions, about its place in society, about its relations with the state.

A believer, who is an internally unified and integral person, is called to implement religious values in all spheres of his life. They are part of the natural attitude of a person’s consciousness and predetermine all his actions. Religion is not aimed at exacerbating the separation of God and the world, but, on the contrary, to bring them, if possible, to unity, basing everything in God. Religious phenomena themselves are dual, symbolic, that is, they are internally addressed to the transcendental world, and externally, in their image, they are immanent in the earthly world and participate in its life. Of course, religious values are based on a person’s relationship to God, but through a religious relationship they are addressed to a specific person who lives in society. In our opinion, the presented understanding of religion and religious values makes possible their dialogue and interaction with secular society and secular values.

In addition, religion carries out its mission in a certain cultural and historical world and in relation to a person who is the bearer of a cultural tradition. Although religion cannot be reduced to any form of culture, it often acts as the “leaven of too many and different cultures” or even civilization. Religious values are organically woven into the fabric of the national culture of a people or a number of peoples in the event of the emergence of civilization. Religion becomes a culture-forming factor, the keeper of national traditions, the soul of national culture. The classic of religious studies M. Muller believed that there is a “close connection between language, religion and nationality.” In history we observe the interrelation, mutual influence, interaction of national and religious values. Religion influences culture, but culture also influences religion, although the “internal territory” of religion that we have designated remains unchanged. As a result, religion acquires special features. For example, Islam in Kazakhstan differs from Islam on the Arabian Peninsula, where it originated, or Russian Orthodoxy differs from Greek Orthodoxy.

Thus, having examined religious values in the context of religion itself as a person’s relationship with God, we came to the conclusion that the determining factor in this regard is the desire for unity with God, which is expressed by love in the ontological, epistemological and moral sense. Love appears in religion as the highest value. In terms of the possibility of interaction between religion, religious values and secular values, in religion as a holistic phenomenon we have identified the “internal territory”, the fundamental foundations of faith that cannot be changed. This includes, firstly, religious experience as a living relationship - a meeting of a person with God, a space of dialogue between a person and God. Secondly, dogmatic definitions expressing and protecting the foundation of faith. Thirdly, religious cult, through which a religious community establishes its relationship with God. These relationships are mediated symbolically through objects of worship, worship, and liturgy. The cult side is essential for every religion, “for religion should allow the believer to contemplate the “holy” - which is achieved through cult actions.” In addition to this unchangeable core, religion has outer boundaries where dialogue and interaction with secular values is quite possible. This is the social aspect of the existence of religion, for example social ethics. In addition, the cultural and historical aspect of religion, within the framework of which interaction with the culture of a particular people is carried out.

The religious picture of the world presupposes, first of all, an understanding of the beginning of the world, its nature, and existential status. The religions of the Abrahamic tradition affirm the creation of the world by God “out of nothing” (ex nihilo), that is, creationism. It should be noted that in the religions under consideration, the creation of the world by God out of nothing is not just one of the statements, but a dogma of faith, without revealing which it is impossible to understand the essence of religion. All the talk about the fact that the natural scientific discoveries of evolution, Big Bang refute the creation of the world by God are absurd, since religion speaks of creation on a phenomenological plane. This means that its goal is not to reveal the laws of development of the Universe, but to show the meaning and meaning of the entire existing Universe and especially human life. For religion, what is important is not just the fact of the world’s existence, but the possibility of its meaningful existence.

Let's take a closer look at the creation of the world. At the beginning of the world there was God, nothing existed outside of God, God created everything - time, space, matter, the world as a whole, man. Further, creation is an act of the Divine will, and not an outpouring of the Divine essence. As the Russian religious philosopher V.N. writes. Lossky: “Creation is a free act, a gift of God. For the Divine being, it is not determined by any “internal necessity.” The freedom of God brought into being all of existence and endowed it with such qualities as order, purposefulness, and love. Thus, the world is defined as created, dependent on God, the world does not have its own foundation, for the created world the constitutive relation is the relation to God, without which it is reduced to nothing (nihilo). The meaning of the dogma of creation was expressed very correctly by one of the leading theologians of our time, Hans Küng: “Creation “out of nothing” is a philosophical and theological expression, meaning that the world and man, as well as space and time, owe their existence to God alone and to no other reason... The Bible expresses the conviction that the world is fundamentally dependent on God as the creator and sustainer of all existence and always remains so.” In the Quran, this idea is expressed not only through the creation of the world by Allah (halq), but also through the power of Allah (amr, malakut) over the existing world: “To Him belongs what is in the heavens, and what is on earth, and what is between them, and what is under the ground" (Quran 20: 6). Researcher M.B. Piotrovsky emphasizes: “This power continues what was started during creation, it constantly supports the movement of the stars, the flow of waters, the birth of fruits, animals and people.” Religion places man, starting from creation, in a space of meaning and life, and provides a meaningful basis for his existence. Therefore, you should not focus on the parallels between natural scientific discoveries and the Holy books (the Bible, the Koran), or look for scientifically provable truths in them. Here again we quote the words of Hans Küng: “The interpretation of the Bible should not find the grain of what is scientifically demonstrable, but what is necessary for faith and life.” Physicist Werner Heisenberg believed that the symbolic language of religion is “a language that allows us to somehow talk about the interconnection of the world as a whole, discerned behind the phenomena, without which we could not develop any ethics or morality” [Cit. according to 23, p.149]. The creation of the world by God affirms the basis of the values of everything that exists and the meaning of everything that exists.

In this context, the Eastern Church Fathers interpret the words of St. John the Theologian: “In the beginning was the Word” (John 1:1). In the beginning there was the Word - the Logos, and the Word is a manifestation, a revelation of the Father, that is, the Son of God - the hypostasis of the Most Holy Trinity. In fact, the Word-Logos-Son of God gives meaning to all existence. This finds expression in Christian Orthodox theology, where the prevailing belief is that each creature has its own logos - “essential meaning”, and Logos - “the meaning of meanings”. The Eastern Fathers of the Church used the “ideas” of Plato, but overcame the dualism inherent in his concept, as well as the position of Western Christian theology, coming from St. Augustine, that ideas are the thoughts of God, contained in the very being of God as definitions of the essence and cause of all created things. The Greek church fathers believed that His essence exceeds ideas, the ideas of all things are contained in His will, and not in the Divine essence itself. Thus, Orthodox theology affirms the novelty and originality of the created world, which is not simply a bad copy of God. Ideas here are the living word of God, an expression of His creative will, they denote the mode of participation of created being in Divine energies. The logos of a thing is the norm of its existence and the path to its transformation. In all that has been said, it is important for us to constantly emphasize in religions the meaningfulness and value of existence. Accordingly, the next most important concept characterizing religion is teleology, that is, orientation towards purpose and meaning.

The very steps of creation - the Sixth Day - indicate its purpose and meaning. As rightly noted by V.N. Lossky: “These six days are symbols of the days of our week - rather hierarchical than chronological. Separating from each other the elements created simultaneously on the first day, they define the concentric circles of existence, in the center of which stands man, as their potential completion.” The same idea is expressed by a modern researcher of theological issues A. Nesteruk, speaking about “the opportunity to establish the meaning of creation laid down by God in his plan for salvation.” That is, the history of human salvation through the incarnation of the Logos in Christ and the resurrection of Christ was initially an element of the Divine plan. Thus, the creation of the world is deeply connected with the creation of man and the event of the incarnation of the Son of God. Moreover, from the beginning of the creation of the world, the eschatological perspective of everything that happens is clearly visible - the direction towards the end. Already creation is an eschatological act, then the incarnation of the Son (Word) of God gives the vector of movement of the entire historical process towards the establishment of the Kingdom of God, which in the Christian religion means achieving unity with God by involving the entire creation in the process of deification. We also find an eschatological orientation in the Koran, in which “mentions of creation also serve as a confirmation of the possibility of the coming judgment, when all people will be resurrected and appear before Allah, their creator and judge.” Consequently, eschatology is the next fundamental characteristic of religion as a person’s relationship to God.

Summarizing all that has been said, we formulate the following conclusions. The dogma of the creation of the world by God out of nothing states the following. The first is the transcendence and at the same time the immanence of God to the world. After all, God created the world and in Him the world finds its foundation. The second is the order and unity of creation, and most importantly the value of everything created, all things. Here the value of all created matter is affirmed, which cannot be destroyed with impunity. God Himself created it and said it was good. Accordingly, when in the Bible we find that God gave the earth to man and declared, “Fill the earth, and subdue it, and have dominion...” (Gen. 1:28), this does not mean exploiting the earth, but cultivating and tending it. To “have dominion” over animals means to be responsible for them, and to “name” animals means to understand their essence. Our position regarding the creation of the world coincides with the point of view of the modern theologian G. Küng: “Belief in creation does not add anything to the ability to manage the world, which has been infinitely enriched by natural science; this belief does not provide any natural science information. But faith in creation gives a person - especially in an era of rapidly occurring scientific, economic, cultural and political revolutions leading to a departure from his roots and a loss of guidelines - the ability to navigate the world. It allows a person to discover meaning in life and in the process of evolution, it can give him a measure for his activities and the last guarantees in this vast, vast universe." The main conclusion from the dogma of creation is that man and the world have meaning and value, they are not chaos, not nothing, but creations of God. This statement defines the ethics of a person’s relationship to the world. Firstly, to respect people as our equals before God, and secondly, to respect and protect the rest of the non-human world. Faith in God the Creator allows us to perceive our responsibility for other people and the world around us, because man is “the deputy of Allah” (Koran 2: 30), his deputy on earth. The third fundamental conclusion from the dogma of creation is the dignity of man. Man is the image and likeness of God, he is placed above all other creations as a ruler.

Let us turn to the doctrine of man in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. These religions created a theology of man. First, a few comments need to be made. As the Orthodox theologian P. Evdokimov notes, in order to adequately understand the doctrine of man in Christianity, it is necessary to abandon the dualism of soul and body and the thesis of their conflict. These religions view man as a multi-level, hierarchical, but holistic being, uniting all plans and elements of man in the spirit. The conflict that accompanies human existence is transferred to a completely different perspective, namely “the thought of the Creator, His desires oppose the desires of the creature, holiness to the sinful state, the norm to perversion, freedom to necessity.” Thus, the central problem of religious anthropology is human freedom.

The beginning of religious teaching about man is the creation of man by God. That is, God sets the nature of man. IN Old Testament, in the book of Genesis, God created man on the sixth day in his own image and likeness and said that “every good thing” was created. In the Jewish spiritual tradition of the Agade, part of the Talmud, the creation of man is described as follows: “From all ends of the earth, specks of dust flew down, particles of that dust into which the Lord breathed a life-giving principle, a living and immortal soul” (Sang., 38). Man is created in the image and likeness of God. In the very creation of man lies his dual nature: the body consists of “dust of the earth” and the soul, which God breathed into man. The word “Adam”, on the one hand, is derived from the word “adama” - earth (human body). On the other hand, from the word “Adame” - “I become like” God, this embodies the supernatural principle of man. Thus, man is twofold: an immortal soul and a mortal body.

Christianity continues this line and the central position of this religion is the postulate - man is the image and likeness of God. The Eastern Orthodox tradition of Christianity emphasizes the divine element human nature- the image of God. In short, the Image of God is the divine in man. The Eastern Church Father Saint Athanasius the Great emphasizes the ontological nature of communion with the deity, and creation means communion. This is where man’s ability to know God originates, which is understood as cognition-communion. Holy Father Gregory of Nyssa noted: “For the first dispensation of man was in imitation of the likeness of God...”. He points to the godlikeness of the human soul, which can be compared to a mirror reflecting the Prototype. Gregory of Nyssa goes further in revealing this concept. The image of God points us to the level of the unknowable, hidden in man - the mystery of man. This mysterious ability of a person to freely define himself, make a choice, make any decision based on himself is freedom. The Divine Personality is free and man as an image and likeness is a person and freedom. Gregory of Nyssa writes: “... he was the image and likeness of the Power that reigns over everything that exists, and therefore in his free will he was similar to the one who freely rules over everything, not submitting to any external necessity, but acting at his own discretion, as it seems to him , choosing better and arbitrarily what he pleases” [Cit. according to 28, p.196]. In general, if we summarize patristic theology, we can come to the following conclusion. An image is not a part of a person, but the whole totality of a person. The image is expressed in the hierarchical structure of man with his spiritual life in the center, with the priority of the spiritual. In Judaism and Islam, the Law prohibits the creation of man-made images, since the image is understood dynamically and realistically. The image evokes the real presence of the one it represents.

Image is the objective basis of a human being, it means “to be created in the image.” But there is also a similarity, which leads to the need to act, to exist in the image. The image manifests itself and acts through subjective similarity. This position is explained by Saint Gregory Palamas: “In his being, in his image, man is superior to the angels, but precisely in his likeness he is lower, because it is unstable...and after the Fall we rejected the likeness, but did not lose being in the image” [Cit. according to 26, p.123]. Thus, the thesis about “man as the image and likeness of God” leads us to an understanding of the human personality in religion. Christianity uses the terms prosopon and hypostasis to reveal the concept of personality. Both terms refer to the face, but emphasize different aspects. Prosopon is human self-awareness, which follows natural evolution. Hypostasis, on the contrary, expresses the openness and aspiration of the human being beyond its limits - towards God. Personality is a body-soul-spirit complex, a center, the life principle of which is hypostasis. In this sense, the secret of personality is in its overcoming itself, in transcending to God.

Hypostasis points us to the incomprehensible depth of the human personality in which the meeting with God takes place. Orthodoxy speaks of union with God, which leads to the deification of man, to the God-man. Sufism, as a mystical tradition of Islam, affirms the possibility of merging with the Divine. This depth is indicated by the heart symbol. In particular, Abu Hamid al-Ghazali writes: “If the heart becomes pure, then perhaps the Truth will appear to it...” The heart is a place of divine habitation, an organ of knowledge of God as communion with God. A person is determined by the content of his heart. Love for God can dwell in the heart, or in the depths of his heart a person can say “there is no God.” Therefore, the heart is not simply the emotional center of the human being, it is the seat of all the faculties of the human spirit. The heart has hierarchical primacy in the structure of the human being.

So, religious anthropology views man as an integral, hierarchical being with a center - a heart, which brings together all the abilities of the human spirit. Hierarchy always presupposes subordination. Accordingly, in a religious worldview, priority is given to the spiritual layers, to which the mental and physical layers must be subordinated. At the same time, the value of the body and soul is not rejected; on the contrary, the Apostle Paul reminds us that “the body is the Temple of God,” and Muhammad in his hadiths speaks of the need to take care of one’s own body. The question is what will become the content of the human heart, what will a person be guided by love for God or love for himself. This is already the result of his choice.

Man as a god-like being, as a person – a divine person – is constituted by freedom. Therefore, the central theme of religious anthropology, regardless of the form of religion, is always human freedom. But, not just an abstract concept of human freedom, but in the aspect of the relationship of human will to God's will. Accordingly, the next position of religious anthropology is the fall of man, the theme of sin, which goes to the problem of the origin of evil in the world - theodicy. On the one hand, a person in a religious worldview is an ontologically rooted being, rooted in a Supreme reality that surpasses him. The attribution of human existence to this Supreme Value gives dignity and lasting value to man himself. On the other hand, religious anthropology points to the damaged nature of man caused by the Fall. If initially, as the image and likeness of God, man is an ontologically rooted integral being, then a sinful man is a fragmented man who has lost his integrity, closed in his own self, dominated by “disorder, chaos, confusion of ontological layers.”

The religious understanding of freedom comes from two premises: on the one hand, from the recognition of the dignity of man, on the other hand, from the recognition of his sinfulness. When the philosopher E. Levinas explores the uniqueness of the Jewish spiritual tradition, he comes to the conclusion about the “difficult freedom” of man in Judaism. Firstly, Judaism as a monotheistic religion removes a person from the power of the magical, sacred, which dominated a person and predetermined his life. As E. Levinas notes: “The sacred that envelops and carries me away is violence.” Judaism as a monotheistic religion affirms human independence and the possibility of a personal relationship with God, “face to face.” Throughout the Tanakh - the Hebrew Bible - God talks to people, and people talk to God. Thus, a dialogical relationship develops between God and people, which is a form of genuine communication. To communicate, according to E. Levinas, means to see the face of another, and to see a face means to affirm oneself personally, because the face is not just a set of physiognomic details, but a new dimension of the human being. In this dimension, “being is not simply closed in its form: it opens, establishes itself in depth and reveals itself in this openness in some way personally.” For M. Buber, the “I - You” relationship is the basis of genuine communication, in which the other is understood not as an object, but as a unique, irreplaceable existence. The relationship with the Other as “I – You” leads to the formation of a person’s self-awareness.

A. Men shares the same point of view. He notes that after the Torah was given to Moses: “From now on, the history of religion will not only be the history of longing, longing and searching, but will become the history of the Covenant,

In the summer of 1893, the publisher of the magazine “Ethische Kultur”, the founder of the “Ethical Society for the Promotion of Social and Ethical Reforms”, professor at the University of Berlin G. von Gizycki addressed L. N. Tolstoy with a letter, asking the writer to answer a number of questions, including there was also this one: “Do you believe in the possibility of morality independent of religion?” Tolstoy became interested in the task assigned to him and formulated his vision of the problem in his work “Religion and Morality.”

More than a hundred years later, this little story from the life of the great writer has a continuation. In 2010, the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the international Knowledge Foundation announced an open competition of philosophical treatises on the topic “Is morality possible, independent of religion?” Its future participants were asked to answer the question once asked to Tolstoy, taking into account the changes that have taken place in the world and modern sociocultural realities. About 250 works from Russia and Russian abroad were submitted to the competition.

The author of this book had the opportunity to participate in that competition with the essay “Secular and theonomous types of morality: a comparative cultural-anthropological analysis” and even be among the winners. Below is the text of this work.

Incorrectness of Professor G. von Gizycki's question

In more than a hundred years that have passed since L. N. Tolstoy wrote his small treatise “Religion and Morality,” his compatriots not only have not moved forward in understanding the problems raised in it, but, on the contrary, have been thrown back to the positions from which these questions are presented even more complex, confusing and intractable than during the life of the Yasnaya Polyana sage. What has remained in the past is that insight, that refinement of existential reflection that was a feature of Russian thought of the Silver Age and allowed it to penetrate into the depths of the most complex spiritual and moral problems.

During the twentieth century, something irreparable happened: the nation lost a significant part of the intellectual potential that it had accumulated by the end of the Silver Age. The authorities acquired the habit of treating the people in accordance with the recipes not of legal cooperation, but of domination-subordination, and the people they led found themselves immersed for a whole century in a state where it became almost impossible for the majority to live according to the laws of honor and dignity, and only a few dared to do so. Faith and morality have devalued to such an extent that people who possess them find themselves in the position of inconvenient nonconformists who do not fit into the usual sociomoral landscape and cause either genuine amazement or irritation of those around them. The catastrophic state of spirituality has ceased to frighten anyone, just as the gloomy forecasts for the future of the nation, which is declining at an alarming rate, losing a million of its citizens every year and having very vague ideas about possible ways out of the demographic and spiritual impasses, have ceased to frighten.

And so, in these conditions, eternal questions are again put on the agenda, which must be answered first of all to ourselves and, first of all, because it is impossible for a person, society, or state to live a normal, civilized life without knowing the answers to them. . You can, of course, turn everything into another intellectual game of solving ancient ethical problems inherited from the times of classical moral philosophy, and thereby compete with its luminaries in ingenuity and wit. This path seems tempting, and the current postmodern era is pushing us towards it, tempting us with the easy, non-committal playful unpretentiousness of this option. However, the same spirit of postmodernity (and in this it should be given its due) also offers another path - the path of a completely serious and responsible deconstruction of the semantic substructures that constitute the rational basis for the question of Professor G. von Gizycki addressed to L. N. Tolstoy: “Is it possible to have morality independent of religion?” This second path allows us to perceive this questioning not as an abstract theoretical fragment of the philosophical “bead game”, but as a pressing existential problem of our today’s existence, which has a number of theoretical dimensions of a metaphysical, ethical, theological, sociocultural, and anthropological nature.

Strictly speaking, the formulation of G. Gizycki’s question can hardly be considered correct, since it seems to initially place morality independent of religion, that is, secular morality, not in the semantic space of basic philosophical categories possibilities And reality, but exclusively only in the semantic context of one concept possibilities. And this looks, at least, strange, since secular morality has long been not a project with a probabilistic, problematic futurology, but the most real of realities.

We can say that the question of the possibility of non-religious morality is largely rhetorical in nature, since the socio-historical and individual-empirical experience of many generations of people indicates the undoubted possibility of the existence of secular morality. The Western world in recent centuries has developed predominantly in a secular direction, and at present its achievements along this path serve as perhaps the main arguments in favor of the legitimacy of the strategy of non-religious development of society, civilization and culture.

This question was obviously legitimate at the dawn of civilization, when they were asked by the first generations of intellectual sages who were thinking about the path that humanity should take in order for its social history to be successful and its spiritual life to be as productive as possible - the path, say, proposed the godless initiators of the Babylonian pandemonium, or the path of Moses, who entered into a covenant with God and tried to unswervingly fulfill all the commandments? But today, as well as in the time of L. Tolstoy, G. Gizycki’s question smacks of the spirit of educational rhetoric. Very appropriate in working with high school students and students with the aim of training the culture of their humanitarian thinking, it is hardly legitimate in an academic environment, since we cannot talk about possibilities the existence of something that has long been reality. Secular morality, independent of religion, ignoring transcendental reality, placing God outside the brackets of all its definitions and prescriptions, has existed for centuries and even millennia. Already such an ancient text as the Bible indicates the existence of people with a secular consciousness: “...They lied against the Lord and said: He does not exist” (Jer. 5:12) or: “The fool said in his heart: “There is no God” (Ps. 13, 1). And although in these judgments about the ancient bearers of secular consciousness there is a powerful evaluative component (characterizing them as liars and madmen), this does not prevent us from noting their ascertaining nature. The biblical text really states: people who deny God, but at the same time adhere, albeit very weakly, to some of their own, "independent of religion" sociomoral norms existed in the archaic world. And although they were the exception rather than the rule, ancient society somehow tolerated their existence, did not consider them overly dangerous criminals, did not take them into custody, and only in some cases, in the presence of additional aggravating circumstances, isolated or executed them. Many of them lived long lives, “ate bread without calling on the Lord,” gave birth and raised children, and participated in the public life of their peoples and states.

Thus, moral consciousness, independent of religion, is the oldest of sociocultural givens, an undoubted reality. Professor Gizycki's question would probably hit the bull's eye if it weren't about possibilities existence of morality free from religion, but about the degree of its productivity in conditions modern civilization. Tolstoy, however, did not attach any importance to this incorrectness of the question posed, easily grasping its true essence. This incorrectness also does not prevent us from thinking about what spiritual, social, and cultural consequences entail both morality independent of religion and morality based on religion.

It is impossible not to notice that Giżycki’s question introduces consciousness into the semantic space of antinomy, where the thesis states: “Morality independent of religion is possible” and the antithesis reads: “Morality independent of religion is impossible”. On its basis, in turn, another antinomy can be formed: “ Secular morality has the right to exist” (thesis) - “Secular morality has no right to exist” (antithesis). And this is a different mode of reflection, transferring discussions about religion and morality from the semantic plane of the categories of possibility and reality into the polarized discursive space of ethical and deviantological categories due And undue where there are endless ideological and ideological battles between atheists and believers. Each side has its own picture of the world, and with it a related cultural tradition-paradigm: in one case anthropocentric, and in the other - theocentric. The reflective mind has the ability to join only one of the poles. At the same time, he cannot act by casting lots, but must carry out rather labor-intensive analytical work of weighing both thesis and antithesis on the scales of reflection, examining the semantic, axiological and normative components of each, identifying the possible consequences that each choice option is fraught with, including including existential consequences for the individual and sociocultural consequences for society.

Both antinomies, with all the ambiguity of their value-orientation functions, have one undeniable advantage: they open up a perspective for modern humanitarian thinking that, say, twenty-five years ago, was hidden from Russian philosophical and ethical thought. Caught in the snare of atheism, languishing in them and losing spiritual, intellectual strength, isolated from antinomic spheres of this kind, wherever equally there were worldview theses and antitheses with such different semantic orientations, normative colors and axiological perspectives, she finally found the freedom of intellectual excursions into the most diverse areas of what is and what should be. And the right to take advantage of the fullness of intellectual freedom is today no longer so much an opportunity as duty professional philosophical and ethical consciousness.

Secularization of morality as a sociocultural reality

Both religious and secular morality have their own sociocultural traditions. Behind the first is a large, long-lasting one, lasting thousands of years, behind the second is a relatively short one, lasting only a few centuries. Secular morality differs from morality in the religious rooting of its structures not in the absolute immutability of the transcendental world of higher transcendences, but in the earthly reality of this world, where all forms of what is and should be stamped with variability and relativity. The historical transformation of religious morality into secular, as a result of which personal unbelief became not the exception, but the rule, and non-believers turned from a small social group into a gigantic mass of atheists-god-fighters, meant that in the eyes of the latter, the religious tradition lost its authority and attractiveness, religious experience and religious motivation lost its attractiveness, faith was crowded out of consciousness by stereotypes of a scientific-atheistic world interpretation with their characteristic strategy of refusal to recognize the transcendental dimension of existence, culture and morality.

To a non-religious consciousness, the historical process of secularization of culture and morality appears to be purely positive, progressive and desirable. When it welcomes such a course of events and openly rejoices at it, then most often the metaphorical logic of naturalistic assimilation of this process to the organic maturation of a person is included: they say, the naive youth of the human race with its illusions and fantasies is replaced by the time of maturity, the ability to look soberly and sensibly at world. And it must be admitted that this logic of reasoning works almost irresistibly in a huge number of cases. The name of God, the concept of faith, the authority of the church immediately lose their former significance, fade and begin to be considered as something transitory, doomed to give way to things more serious and important, which cannot be compared with the old fantasies and prejudices inherited from long-vanished generations . The atheistic mind deprives religious and theological ideas of legitimacy and deprives them of the right to occupy their rightful place in the discursive space of modern intellectual life. Like, just as an adult should not be like a green youth, so mature humanity should not amuse itself with children's fairy tales about the creation of the world, the Tower of Babel, the great flood, etc., when more and more super-serious problems are approaching from all sides, requiring gigantic intellectual and material costs, extremely responsible decisions and urgent actions.

The secularization of morality was greatly facilitated by changes in the social structure of society. If the main institutional pillar supporting religious morality has always been the church, then the state and society (civil society) have served and continue to serve as the institutional forms that ensure the existence of secular morality. The fact that in the modern world the authority of the state and civil society significantly exceeds the authority of the church, and the quantitative superiority of atheists over believers is a socio-statistical reality both in Western countries and in Russia, has resulted in the real superiority of secular moral systems over religious moral systems.

Modern

The peculiarity of secularism is that within the cultural spaces it protects, spiritual experience associated with absolute values and the highest meanings of existence is almost not produced or multiplied. Modernity, which gave birth to militant atheism, this most severe and merciless form of secularism, allowed for the annihilation of spirituality, unprecedented in its destructive power. As a result, the postmodern consciousness that replaced it found itself in a state of depressing spiritual exhaustion. Little suitable for reproducing higher meanings and values, it plunged mainly into entertaining, often frankly frivolous games with heterogeneous semantic figures and axiological forms. Not having enough of them in its own creative economy, it began to turn to past cultural eras, remove them from there and enjoy them, often showing remarkable ingenuity.

Postmodernism turned out to be heterogeneous in the quality and direction of the ideas that exist under its guise. Without delving into the details of their substantive differentiation, we can say that in the entire postmodern socio-humanitarian discourse two main directions are visible. The first is the aggressive fight against God inherited from the modern era, preaching ideological nihilism and methodological anarchism. In these manifestations, postmodernity is nothing more than late modern, striving wherever the modernist consciousness managed to say only “a”, declare both “b” and “c”, etc., that is, to finish what his “parent” did not manage to do, to dot all the “i”s . Such postmodernism continues to be in open opposition to the classical spiritual heritage in its biblical Christian version. The only thing that distinguishes it from modernism is a higher degree of sophistication and refinement of its reflections, more subtle, often simply filigree strategies of intellectual terror directed against everything in which signs of absolute meanings, unconditional values and universal moral and ethical norms are seen. And in this sense, late modernity/postmodernity looks like a purely negative paradigm, whose purpose is to introduce the “torn” and “unhappy” consciousness of the modern intellectual into a state of twilight and even greater spiritual eclipse.

However, fortunately, this highway is not the only one in postmodern discourse. It is accompanied or, more precisely, opposed by another, directed in a completely different direction. Its representatives are confident that the postmodern world is gradually parting with secularism and entering a post-secular era. They are convinced that modernism has managed to destroy everything that could be destroyed in the spiritual world of modern man. And, just as in fine art it is impossible to move beyond a “black square on a white background,” much less a “black square on a black background” or a “white square on a white background,” so in an epoch-making spiritual situation the only possible saving path is - this is a turn back to absolute values and meanings, similar to the return of the prodigal son to his once abandoned father's house. Of course, this is not a readiness to literally move backwards, but an invitation to re-evaluate the intellectual achievements of modernity and stop admiring its picturesque “squares” and musical cacophonies, free yourself from the dark spell of the principles of methodological atheism and anarchism, put everything in its place, call nonsense nonsense, emptiness emptiness , and darkness is darkness. That is, to move forward into new spiritual perspectives, but not on the basis of extremely relativized conventions, reduced cultural meanings, spiritually depleted quasi-values of modernity, but with the help of good, first-class values and meanings available in the spiritual baggage of humanity, although pushed aside by modernism to the far corner of the world spiritual economy. By turning to them, a postmodern person gets the opportunity to demonstrate not the inertia and routineness of thinking, but its quality, which N. Berdyaev once called “noble fidelity to the past.”

Thus, within the current cultural era, the competition between the decentered and theocentric models of the world continues, and the agonies of the paradigms of secularism and theism continue. And in this, strictly speaking, there is nothing new or unusual, since the mentality behind the rival parties has always existed, starting from the biblical times of the dialogue between Eve and the serpent tempting her. There is, in fact, an eternal, enduring antithesis, a global and at the same time deeply personal conflict, about which it is said: “There the devil and God are fighting, and the battlefield is human hearts.” The inner worlds of millions of people, along with the cultural spaces of a number of civilizations, have been such fields of spiritual battles for thousands of years. The modern space of culture continues to remain the same field, together with the discourses of various socio-humanitarian disciplines included in it - philosophy, ethics, aesthetics, cultural studies, art history, literary criticism, psychology, jurisprudence, sociology, etc.

If we talk about the normative value field of morality/morality, then it has almost never been something single and integral. And today it is fragmented along very different lines and directions, and its division into religious and secular morality is one of the fundamental divisions. Neither one nor the other can be ignored or discounted. Neither one nor the other lends itself to unambiguous assessments and does not fit into the confines of a black-and-white evaluation palette. The reasons for this ambiguity lie not only in the content of systems of secular and religious morality, but also in man himself - in the anthropological features of his being, in the inescapable contradictions of his social and spiritual existence, in his ineradicable tendency with depressing regularity to burn what he worshiped and to worship that , which he previously burned, in his easily flaring readiness to both belittle the high and elevate the base and in many other ways...

A modern person can either rejoice in the fact that for millions of people morality and religion find themselves on opposite sides of the “mainstream” of current life, or they can complain about this circumstance. Both mentalities are natural, completely understandable reactions to this reality. The first type of reactions, as mentioned above, is due to the fact that this process is placed in the context of the categories of the dynamic logic of the maturation of the human race, as if gradually freeing itself from the naive illusions of childhood and adolescence. Various social collisions, shocks, crises, catastrophes in this case look like just a consequence of certain processes that are not directly related to the topic of distancing morality from religion.

The second type of reactions presupposes a different intellectual attitude, where the same process of distance, detachment, alienation of morality from religion is considered in deviantological categories, i.e. it is assessed as macrohistorical, geocultural deviation, which has as its direct consequences countless different harmful social, cultural, and spiritual transformations.

God's Universe and the Guttenberg Galaxy: Humanitarian Methodologies of Inclusion and Exclusivity

The discursive spaces formed by the descriptive-analytical efforts of atheist scientists and Christian scientists form two significantly different intellectual worlds. But despite all the dissimilarities in the spiritual experience that feeds them, despite the obvious differences in their ideological foundations, analytical methods, and languages, they are not strangers to each other. They have a lot in common, and first of all, they are brought together by their interest in the same object - moral and ethical reality in all the fullness of its socio-historical manifestations, in all the axiological diversity of its forms, in all the polyphonic diversity of its meanings.

The problem of the relationship between religion and morality is interesting not only because of the complexity of its epistemological structure. Giving rise to reflection on very subtle matters, it also has a purely spiritual value, since it introduces analytical consciousness into a significantly expanded intellectual space, into an incredibly expanded sphere of cultural meanings.

Position inclusivity, including God in the pictures of the universe and culture, and the position exclusivity, excluding God from the cultural-symbolic “Guttenberg Galaxy” entail the emergence of two types of moral consciousness, radically different from each other, having different ontological, axiological and normative foundations, dissimilar motivational structures, and non-coinciding existential vectors. In a similar way, the rational constructions of theoretical reflections built on top of them also form significantly different methodologies of philosophical and ethical knowledge. Here, with striking clarity, it is revealed how the nature of the scientist’s personal relationship with God changes the entire structure of his analytical thinking, for which the acceptance of the world by reason is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for building a relationship with him that is complete in his eyes. And only faith brings the desired balance to these relationships. Inclusiveness complicates the structure of the worldview, expands and deepens its content, takes it out of the closed areas of secularly oriented naturalism, atheistic sociologism and mundane-empirical anthropologism into the boundlessness of the theocentric picture of the cultural-symbolic world. It makes it possible to analyze social and moral reality not as closed, autonomous and self-sufficient, but as being in direct relationship with transcendental reality, with the endless world of the absolute and inescapable.

The methodology of exclusivity is based on the act of removing God from the core of the world order, denying the order of things approved by God, and with it systems of absolute meanings, values and norms, universal constants of truth, goodness and beauty. This act, through which a person “declares willfulness,” acts as a determining ideological determinant, under the direct influence of which modern philosophical and ethical consciousness continues to exist. The methodology of exclusivity he uses, which desacralizes morality, decenters the world of moral values and norms, and rejects everything that bears the stamp of transcendence, carries a fairly strong reductive spirit. In extreme cases, as was the case, for example, during the reign of Soviet militant atheism, the content of scientific and theoretical constructions of professional humanities scholars often reached such a degree of simplification that their texts turned into simple tracings of not too intricate constructions of state ideology with its idea complete extinction of religion.

In other cases, it comes to paradoxes. When secular consciousness believes that the foundations of its discursive structures are of a “premiseless” nature, based on some completely “pure” fundamental principle, not mixed with any of the existing religious and cultural traditions, then this desire to actually rely on the world-contemplative emptiness is portrayed as something positive, valuable, innovative. This emptiness itself is understood in two ways: on the one hand, it is the Universe in which there is no God and is left to itself, and on the other hand, it is a person not bound by any spiritual traditions, not burdened by burdensome religious experience. It turns out that the homeless Universe and the internally emasculated person constitute the necessary and sufficient ontological-anthropological basis for rational thinking, capable of demonstrating unprecedented autonomy. However, one cannot help but see that in such cases, secular consciousness, instead of gaining freedom of intellectual research, falls into just another dependence of the most banal nature - it turns out to be a captive of relativism and reductionism. The break with the world of absolutes turns for him into subordination either to external state-ideological engagements, or to the whims of such a customer as the pragmatic mind, which is inclined to become dependent on the flat constructs of neo-positivist, neo-Darwinian, neo-Marxist, neo-Freudian and other interpretations.

In fairness, it should be admitted that in the scientific world of the modern era there were always analysts who were not attracted to the slightest degree by positivism, materialism, Marxism, and atheism. Convinced that the affinity of science, philosophy, ethics with theology does not harm them at all, but, on the contrary, gives theoretical thought a special axiological coloring, introduces it into a sublime spiritual register, they attached special importance to such a cultural context in which extensive philosophical reasoning is impossible about anything base or unnatural, be it the desecration of shrines, the passions of Sodom, or metaphysical walks through landfills and cemeteries. In such a discursive space, a climate of voluntary moral and ethical self-censorship appears as if by itself. Discursive studies unfold strictly within the limits of religious and moral self-restraints that scientists impose on themselves, and which, with their disciplinary essence, go back to the old, but not aging biblical commandments. The latter helped and continue to help theoretical consciousness to discern significant connections with the universal whole, in which transcendental reality is not supplanted by anyone, but takes its ontologically legitimate place, where the unshakable principles of the axiological hierarchy dominate, where religious values and theological meanings are not banished to the periphery of intellectual life, but are at its forefront. The subjective determinant of this position has always been the personal faith of the scientist, which allowed him to assign any discursive material a place corresponding to its nature within the theocentric picture of the world.

When the ideological sword categorically cut off from axiological-normative integrity "religion-morality" the first half, this turned the works of Russian humanities scholars into texts that amazed and depressed serious readers with their spiritual poverty. Today, these works with excessively simplified conceptual structures are practically not in scientific demand, since it is quite difficult to glean anything valuable from them for understanding the essence of human morality. Their current destiny is to exist as exhibits of a museum of intellectual history, where they resemble dried out, lifeless herbariums, cut off from the nutritious, life-giving soil and no longer giving much to the mind and heart of the modern connoisseur of philosophical and ethical studies.