In medieval times, life was not easy, clothing played an important role in the flesh to preserve life.

Simple clothing made of flimsy fabric was common, leather was considered a rarity, but armor was worn only by wealthy gentlemen.

Henry VIII's Armet, known as the "Horned Shell". Innsbruck, Austria, 1511

There are several versions regarding the appearance of the first armor. Some believe it all started with robes made of forged metal. Others believe that wood protection should also be considered, in which case we need to remember the truly distant ancestors with stones and sticks. But most people think that armor came from those difficult times when men were knights and women languished in anticipation of them.

Another strange shell-mask, from Augsburg, Germany, 1515.

A separate article should be devoted to the variety of shapes and styles of medieval armor:

Either armor or nothing

The first armor was very simple: rough metal plates designed to protect the knight inside from spears and swords. But gradually the weapons became more and more complicated, and the blacksmiths had to take this into account and make the armor more and more durable, light and flexible, until they had the maximum degree of protection.

One of the most brilliant innovations was the improvement of chain mail. According to rumors, it was first created by the Celts many centuries ago. It was a long process that took a very long time until gunsmiths took on it and took the idea to new heights. This idea is not entirely logical: instead of making armor from strong plates and very reliable metal, why not make it from several thousand carefully connected rings? It turned out great: light and durable, chain mail allowed its owner to be mobile and was often a key factor in how he left the battlefield: on a horse or on a stretcher. When plate armor was added to chain mail, the result was stunning: the armor of the Middle Ages appeared.

Medieval arms race

Now it's hard to imagine that for a long time the knight on horseback was truly terrible weapon of that era: arriving at the scene of battle on a war horse, often also dressed in armor, he was as terrifying as he was invincible. Nothing could stop such knights when, with a sword and spear, they could easily attack almost anyone.

Here is an imaginary knight, reminiscent of heroic and victorious times (drawn by the delightful illustrator John Howe):

Bizarre Monsters

Combat became more and more “ritualistic,” leading to the jousting tournaments we all know and love from movies and books. Armor became less useful in practice and gradually became more of an indicator of high social level and well-being. Only the rich or nobles could afford armor, however only a truly rich or very wealthy baron, duke, prince or king could afford fantastic armor highest quality.

Did this make them especially beautiful? After a while, the armor began to look more like dinner wear than battle gear: impeccable metal work, precious metals, ornate coats of arms and regalia... All of this, while looking amazing, was useless during battle.

Just look at the armor belonging to Henry VIII: Aren't they a masterpiece of art of that time? The armor was designed and made, like most all armor of the time, to fit the wearer. In Henry's case, however, his costume looked more noble than fearsome. Who can remember the royal armor? Looking at a set of such armor, the question arises: were they invented for fighting or for showing off? But honestly, we can't blame Henry for his choice: his armor was never really designed for war.

England comes up with ideas

What is certain is that the suit of armor was a terrifying weapon of the day. But all days come to an end, and in the case of classic armor, their end was simply worse than ever.

1415 northern France: on the one hand - the French; on the other - the British. Although their numbers are a matter of debate, it is generally believed that the French outnumbered the English by a ratio of about 10 to 1. For the English, under Henry (5th, forefather of the aforementioned 8th), this was not at all pleasant. Most likely, they will be, to use a military term, "killed." But then something happened that not only determined the outcome of the war, but also changed Europe forever, as well as dooming armor as a primary weapon.

Fantasy authors often bypass the possibilities of smoke powder, preferring the good old sword and magic. And this is strange, because primitive firearms are not only a natural, but also a necessary element of the medieval setting. It was no coincidence that warriors with “fiery shooting” appeared in knightly armies. The spread of heavy armor naturally led to an increase in interest in weapons capable of piercing them.

Ancient "lights"

Sulfur. A common component of spells and a component of gunpowder

The secret of gunpowder (if, of course, we can talk about a secret here) lies in the special properties of saltpeter. Namely, the ability of this substance to release oxygen when heated. If saltpeter is mixed with any fuel and set on fire, a “chain reaction” will begin. The oxygen released by saltpeter will increase the intensity of combustion, and the hotter the flame flares up, the more oxygen will be released.

People learned to use saltpeter to increase the effectiveness of incendiary mixtures back in the 1st millennium BC. It was just not easy to find her. In countries with hot and very humid climates, white, snow-like crystals could sometimes be found on the site of old fire pits. But in Europe, saltpeter was found only in stinking sewer tunnels or in populated areas. bats caves.

Before gunpowder was used for explosions and throwing cannonballs and bullets, saltpeter-based compounds had long been used to make incendiary shells and flamethrowers. For example, the legendary “Greek fire” was a mixture of saltpeter with oil, sulfur and rosin. Sulfur, which ignites at low temperatures, was added to facilitate ignition of the composition. Rosin was required to thicken the “cocktail” so that the charge would not flow out of the flamethrower pipe.

The “Greek fire” really could not be extinguished. After all, saltpeter dissolved in boiling oil continued to release oxygen and support combustion even under water.

In order for gunpowder to become an explosive, saltpeter must make up 60% of its mass. In the “Greek fire” there was half as much. But even this amount was enough to make the oil combustion process unusually violent.

The Byzantines were not the inventors of “Greek fire”, but borrowed it from the Arabs back in the 7th century. The saltpeter and oil necessary for its production were also purchased in Asia. If we take into account that the Arabs themselves called saltpeter “Chinese salt” and rockets “Chinese arrows”, it will not be difficult to guess where this technology came from.

Spreading gunpowder

It is very difficult to indicate the place and time of the first use of saltpeter for incendiary compositions, fireworks and rockets. But the credit for inventing cannons definitely belongs to the Chinese. The ability of gunpowder to throw projectiles from metal barrels is reported in Chinese chronicles of the 7th century. The discovery of a method for “growing” saltpeter in special pits or shafts made of earth and manure dates back to the 7th century. This technology made it possible to regularly use flamethrowers and rockets, and later firearms.

The barrel of the Dardanelles cannon - from a similar gun the Turks shot down the walls of Constantinople

At the beginning of the 13th century, after the capture of Constantinople, the recipe for “Greek fire” fell into the hands of the crusaders. The first descriptions of “real” exploding gunpowder by European scientists date back to the middle of the 13th century. The use of gunpowder for throwing stones became known to the Arabs no later than the 11th century.

In the “classic” version, black gunpowder included 60% saltpeter and 20% each of sulfur and charcoal. Charcoal could successfully be replaced with ground brown coal (brown powder), cotton wool or dried sawdust (white gunpowder). There was even “blue” gunpowder, in which coal was replaced with cornflower flowers.

Sulfur was also not always present in gunpowder. For cannons, the charge in which was ignited not by sparks, but by a torch or a hot rod, gunpowder could be made consisting only of saltpeter and brown coal. When firing from guns, sulfur could not be mixed into the gunpowder, but poured directly onto the shelf.

Inventor of gunpowder

Invented? Well, step aside, don't stand there like a donkey

In 1320, the German monk Berthold Schwarz finally “invented” gunpowder. It is now impossible to determine how many people in different countries They invented gunpowder before Schwartz, but we can say with confidence that after him no one succeeded!

Berthold Schwartz (whose name, by the way, was Berthold Niger) of course, did not invent anything. The “classic” composition of gunpowder became known to Europeans even before its birth. But in his treatise “On the Benefits of Gunpowder” he gave clear practical recommendations on the manufacture and use of gunpowder and cannons. It was thanks to his work that during the second half of the 14th century the art of fire shooting began to rapidly spread in Europe.

The first gunpowder factory was built in 1340 in Strasbourg. Soon after this, the production of saltpeter and gunpowder began in Russia. The exact date of this event is not known, but already in 1400 Moscow burned for the first time as a result of an explosion in a gunpowder workshop.

Fire tubes

First depiction of a European cannon, 1326

The simplest hand-held firearm - the hand grip - appeared in China already in the middle of the 12th century. The most ancient samopals of the Spanish Moors date back to the same period. And from the beginning of the 14th century, “fire-fighting pipes” began to be fired in Europe. Hand cranks appear in the chronicles under many names. The Chinese called such a weapon pao, the Moors called it modfa or carabine (hence “carbine”), and the Europeans called it hand bombard, handcanona, sclopetta, petrinal or culverina.

The handle weighed from 4 to 6 kilograms and was a blank of soft iron, copper or bronze drilled from the inside. The barrel length ranged from 25 to 40 centimeters, the caliber could be 30 millimeters or more. The projectile was usually a round lead bullet. In Europe, however, until the beginning of the 15th century, lead was rare, and self-propelled guns were often loaded with small stones.

Swedish hand cannon from the 14th century

As a rule, the petrinal was mounted on a shaft, the end of which was clamped under the armpit or inserted into the current of the cuirass. Less commonly, the butt could cover the shooter's shoulder from above. Such tricks had to be resorted to because it was impossible to rest the butt of the handbrake on the shoulder: after all, the shooter could support the weapon with only one hand, and with the other he brought the fire to the fuse. The charge was ignited with a “scorching candle” - a wooden stick soaked in saltpeter. The stick was pressed against the ignition hole and turned, rolling in the fingers. Sparks and pieces of smoldering wood fell inside the barrel and sooner or later ignited the gunpowder.

Dutch hand culverins from the 15th century

The extremely low accuracy of the weapon allowed effective shooting only from a point-blank range. And the shot itself occurred with a long and unpredictable delay. Only the destructive power of this weapon aroused respect. Although a bullet made of stone or soft lead at that time was still inferior to a crossbow bolt in penetrating power, a 30-mm ball fired at point-blank range left such a hole that it was worth looking at.

It was a hole, but it was still necessary to get in. And the depressingly low accuracy of the petrinal did not allow one to expect that the shot would have any consequences other than fire and noise. It may seem strange, but it was enough! Hand bombards were valued precisely for the roar, flash and cloud of sulfur-smelling smoke that accompanied the shot. Loading them with a bullet was not always considered advisable. The Petrinali-sklopetta was not even equipped with a butt and was intended exclusively for blank shooting.

15th century French marksman

The knight's horse was not afraid of fire. But if, instead of honestly stabbing him with pikes, he was blinded by a flash, deafened by a roar, and even insulted by the stench of burning sulfur, he still lost his courage and threw off the rider. Against horses not accustomed to shots and explosions, this method worked flawlessly.

But the knights were not able to introduce their horses to gunpowder right away. In the 14th century, “smoke powder” was an expensive and rare commodity in Europe. And most importantly, at first he aroused fear not only among the horses, but also among the riders. The smell of “hellish brimstone” made superstitious people tremble. However, people in Europe quickly got used to the smell. But the loudness of the shot was listed among the advantages of firearms until the 17th century.

Arquebus

At the beginning of the 15th century, self-propelled guns were still too primitive to seriously compete with bows and crossbows. But fire tubes quickly improved. Already in the 30s of the 15th century, the pilot hole was moved to the side, and a shelf for seed powder began to be welded next to it. This gunpowder, upon contact with fire, flared up instantly, and after just a split second, the hot gases ignited the charge in the barrel. The gun began to fire quickly and reliably, and most importantly, it became possible to mechanize the process of lowering the wick. In the second half of the 15th century, fire tubes acquired a lock and butt borrowed from the crossbow.

Japanese flint arquebus, 16th century

At the same time, metalworking technologies were also improved. The trunks were now made only from the purest and softest iron. This made it possible to minimize the likelihood of explosion when fired. On the other hand, the development of deep drilling techniques made it possible to make gun barrels lighter and longer.

This is how the arquebus appeared - a weapon with a caliber of 13–18 millimeters, weighing 3–4 kilograms and a barrel length of 50–70 centimeters. An ordinary 16-mm arquebus ejected a 20-gram bullet with an initial speed of about 300 meters per second. Such bullets could no longer rip people’s heads off, but from 30 meters they would make holes in steel armor.

Firing accuracy increased, but was still insufficient. An arquebusier could hit a person only from 20–25 meters, and at 120 meters, shooting even at such a target as a pikeman battle turned into a waste of ammunition. However, light guns retained approximately the same characteristics until the mid-19th century - only the lock changed. And in our time, shooting a bullet from a smoothbore rifle is effective no further than 50 meters.

Even modern shotgun bullets are designed not for accuracy, but for impact force.

Arquebusier, 1585

Loading an arquebus was a rather complicated procedure. To begin with, the shooter disconnected the smoldering wick and put it in a metal case attached to his belt or hat with slots for air access. Then he uncorked one of the several wooden or tin cartridges he had - “loaders”, or “gazyrs” - and poured a pre-measured amount of gunpowder from it into the barrel. Then he nailed the gunpowder to the treasury with a ramrod and stuffed a felt wad into the barrel to prevent gunpowder from spilling out. Then - a bullet and another wad, this time to hold the bullet. Finally, from the horn or from another charge, the shooter poured some gunpowder onto the shelf, slammed the lid of the shelf and reattached the wick to the trigger lips. It took an experienced warrior about 2 minutes to do everything.

In the second half of the 15th century, arquebusiers took a strong place in European armies and began to quickly push out competitors - archers and crossbowmen. But how could this happen? After all, the combat qualities of the guns still left much to be desired. Competitions between arquebusiers and crossbowmen led to a stunning result - formally, the guns turned out to be worse in all respects! The penetrating power of the bolt and the bullet was approximately equal, but the crossbowman shot 4–8 times more often and at the same time did not miss a tall target even from 150 meters!

Geneva arquebusiers, reconstruction

The problem with the crossbow was that it didn't have the same benefits. practical value. Bolts and arrows flew like a fly in the eye during competitions when the target was motionless and the distance to it was known in advance. In a real situation, the arquebusier, who did not have to take into account the wind, the movement of the target and the distance to it, had the best chance of hitting. In addition, bullets did not have the habit of getting stuck in shields and sliding off armor; they could not be dodged. Didn't have much practical significance and rate of fire: both the arquebusier and the crossbowman only had time to fire once at the attacking cavalry.

The spread of arquebuses was restrained only by their high cost at that time. Even in 1537, Hetman Tarnovsky complained that “in Polish army There are few arquebuses, only vile hand-held hands.” The Cossacks used bows and self-propelled guns until the mid-17th century.

Pearl gunpowder

The gazyrs, worn on the chests of Caucasian warriors, gradually became an element of the national costume.

In the Middle Ages, gunpowder was prepared in the form of powder, or “pulp.” When loading the weapon, the “pulp” stuck to the inner surface of the barrel and had to be nailed to the fuse with a ramrod for a long time. In the 15th century, to speed up the loading of cannons, lumps or small “pancakes” began to be sculpted from powder pulp. And at the beginning of the 16th century, “pearl” gunpowder, consisting of small hard grains, was invented.

The grains no longer stuck to the walls, but rolled down to the breech of the barrel under their own weight. In addition, graining made it possible to increase the power of gunpowder almost twice, and the duration of gunpowder storage by 20 times. Gunpowder in the form of pulp easily absorbed atmospheric moisture and deteriorated irreversibly within 3 years.

However, due to the high cost of “pearl” gunpowder, the pulp often continued to be used for loading guns until the mid-17th century. The Cossacks used homemade gunpowder in the 18th century.

Musket

Contrary to popular belief, knights did not consider firearms “non-knightly” at all.

It is a fairly common misconception that the advent of firearms marked the end of the romantic “age of chivalry.” In fact, arming 5–10% of soldiers with arquebuses did not lead to a noticeable change in the tactics of European armies. At the beginning of the 16th century, bows, crossbows, darts and slings were still widely used. Heavy knightly armor continued to be improved, and the main means of counteracting cavalry remained the pike. The Middle Ages continued as if nothing had happened.

The romantic era of the Middle Ages ended only in 1525, when at the Battle of Pavia the Spaniards first used matchlock guns of a new type - muskets.

Battle of Pavia: museum panorama

How was a musket different from an arquebus? Size! Weighing 7–9 kilograms, the musket had a caliber of 22–23 millimeters and a barrel about one and a half meters long. Only in Spain - the most technically developed country in Europe at that time - could a durable and relatively light barrel of such length and caliber be made.

Naturally, such a bulky and massive gun could only be fired from a support, and two people had to operate it. But a bullet weighing 50–60 grams flew out of the musket at a speed of over 500 meters per second. She not only killed the armored horse, but also stopped it. The musket hit with such force that the shooter had to wear a cuirass or a leather pad on his shoulder to prevent the recoil from splitting his collarbone.

Musket: Assassin of the Middle Ages. 16th century

The long barrel provided the musket with relatively good accuracy for a smooth gun. The musketeer hit a person not from 20–25, but from 30–35 meters. But of much greater importance was the increase in the effective salvo firing range to 200–240 meters. At this entire distance, the bullets retained the ability to hit knightly horses and pierce the iron armor of pikemen.

The musket combined the capabilities of the arquebus and pike, and became the first weapon in history that gave the shooter the opportunity to repel the onslaught of cavalry in open terrain. Musketeers did not have to run away from cavalry during a battle, therefore, unlike arquebusiers, they made extensive use of armor.

Because of heavy weight weapons, musketeers, like crossbowmen, preferred to move on horseback

Throughout the 16th century, there remained few musketeers in European armies. Musketeer companies (detachments of 100–200 people) were considered the elite of the infantry and were formed from nobles. This was partly due to the high cost of weapons (as a rule, a musketeer’s equipment also included a riding horse). But even more important were the high requirements for durability. When the cavalry rushed to attack, the musketeers had to repel it or die.

Pishchal

Sagittarius

In terms of its purpose, the Russian archery arquebus corresponded to the Spanish musket. But the technical backwardness of Rus' that emerged in the 15th century could not but affect the combat properties of guns. Even pure - “white” - iron for making barrels at the beginning of the 16th century still had to be imported “from the Germans”!

As a result, with the same weight as the musket, the arquebus was much shorter and had 2–3 times less power. Which, however, had no practical significance, given that eastern horses were much smaller than European ones. The accuracy of the weapon was also satisfactory: from 50 meters the archer did not miss a two-meter high fence.

In addition to streltsy arquebuses, light “mounted” guns (having a strap for carrying behind the back) were also produced in Muscovy, which were used by mounted (“stirrup”) archers and Cossacks. In terms of their characteristics, “curtain arquebuses” corresponded to European arquebuses.

Pistol

Smoldering wicks, of course, caused a lot of inconvenience for the shooters. However, the simplicity and reliability of the matchlock forced the infantry to put up with its shortcomings until the end of the 17th century. Another thing is the cavalry. The rider needed a weapon that was comfortable, always ready to fire and suitable for holding with one hand.

Wheel lock in Da Vinci's drawings

The first attempts to create a castle in which fire would be produced using iron flint and “flint” (that is, a piece of sulfur pyrite or pyrite) were made back in the 15th century. Since the second half of the 15th century, “grating locks” have been known, which were ordinary household flints installed above a shelf. With one hand the shooter aimed the weapon, and with the other he struck the flint with a file. Due to the obvious impracticality, grater locks did not become widespread.

The wheel castle, which appeared at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, became much more popular in Europe, the diagram of which was preserved in the manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci. The ribbed flint was given the shape of a gear. The spring of the mechanism was cocked with the key supplied to the lock. When the trigger was pressed, the wheel began to rotate, striking sparks from the flint.

German wheel pistol, 16th century

The wheel lock was very reminiscent of a watch and was not inferior to a watch in complexity. The capricious mechanism was very sensitive to clogging with gunpowder fumes and flint fragments. After 20-30 shots it stopped firing. The shooter could not disassemble it and clean it on his own.

Since the advantages of the wheel lock were of the greatest value to the cavalry, the weapon equipped with it was made convenient for the rider - one-handed. Starting from the 30s of the 16th century in Europe, knightly spears were replaced by shortened wheeled arquebuses without a butt. Since the production of such weapons began in the Italian city of Pistol, one-handed arquebuses began to be called pistols. However, by the end of the century, pistols were also produced at the Moscow Armory.

European military pistols of the 16th and 17th centuries were very bulky designs. The barrel had a caliber of 14–16 millimeters and a length of at least 30 centimeters. The total length of the pistol exceeded half a meter, and the weight could reach 2 kilograms. However, the pistols struck very inaccurately and weakly. The range of an aimed shot did not exceed several meters, and even bullets fired at point-blank range bounced off cuirasses and helmets.

In the 16th century, pistols were often combined with bladed weapons, such as a club head (“apple”) or even an ax blade.

Except large dimensions, pistols of the early period were characterized by richness of decoration and whimsical design. Pistols of the 16th and early 17th centuries were often made with multiple barrels. Including one with a rotating block of 3-4 barrels, like a revolver! All this was very interesting, very progressive... And in practice, of course, it did not work.

The wheel lock itself cost so much money that decorating the pistol with gold and pearls no longer significantly affected its price. In the 16th century, wheeled weapons were affordable only by very rich people and had more prestige than combat value.

Asian pistols were distinguished by their special grace and were highly valued in Europe

* * *

The appearance of firearms was a turning point in the history of military art. For the first time, a person began to use not muscular strength, but the energy of burning gunpowder to inflict damage on an enemy. And this energy, by the standards of the Middle Ages, was stunning. Noisy and clumsy firecrackers, now unable to cause anything but laughter, several centuries ago inspired people with great respect.

Beginning in the 16th century, the development of firearms began to determine the tactics of sea and land battles. The balance between close and ranged combat began to shift in favor of the latter. The importance of protective equipment began to decline, and the role field fortifications- increase. These trends continue to this day. Weapons that use chemical energy to eject a projectile continue to improve. Apparently, it will maintain its position for a very long time.

A sword is a type of bladed weapon; it was used to inflict piercing, cutting or chopping wounds. Its basic design was simple and consisted of an oblong, straight blade with a hilt. Distinctive feature The weapon is an established minimum blade length of about 60 cm. The type of sword had many variations and depended on time, region, and social status.

There is no reliable information about the date of the first sword. It is generally accepted that its prototype was a sharpened club made of wood, and the first swords were made of copper. Due to its ductility, copper was soon replaced by a bronze alloy.

The sword is undoubtedly one of the most authoritative and historically significant weapons of antiquity. It is commonly believed to symbolize justice, dignity and courage. Hundreds of folk legends were written about combat battles and knightly duels, and swords were an integral part of them. Later, writers, inspired by these legends, created the main characters in their novels in the image and likeness of the legends. For example, the story of King Arthur has been published countless times, and the greatness of his sword has always remained unchanged.

In addition, swords are reflected in religion. The nobility of edged weapons was closely intertwined with spiritual and divine meaning, which was interpreted by each religion and teaching in its own way. For example, in Buddhist teachings, the sword symbolized wisdom. In Christianity, the interpretation of the “two-edged sword” is directly related to the death of Jesus Christ, and carries the meaning of divine truth and wisdom.

Identifying the sword with a divine symbol, the inhabitants of that time were in awe of the possession of such a weapon and the use of its images. Medieval swords had a cross-shaped handle in the image of a Christian cross. This sword was used for knighting rituals. Also, the image of this weapon has found wide application in the field of heraldry.

By the way, in historical documents that have survived to this day there is information about the cost of swords. Thus, the price of one standard gun was equal to the cost of 4 heads cattle(cows), and if the work was performed by a famous blacksmith, the amount of course was much higher. A middle-class resident could hardly afford expenses of this level. High price due to the high cost and rarity of the metals used, in addition, the manufacturing process itself was quite labor-intensive.

The quality of a manufactured sword directly depends on the skill of the blacksmith. His skill lies in the ability to correctly forge a blade from a different alloy of metals, so that the resulting blade is smooth, light in weight, and the surface itself is perfectly smooth. Complex composition products created difficulties in mass release. They began to produce in Europe good swords in large numbers only towards the end of the Middle Ages.

The sword can rightfully be called an elite weapon, and this is due not only to the previously listed factors. Versatility in use and a light weight favorably distinguished the sword from its predecessors (axe, spear).

It is also worth noting that not everyone can wield a blade. Those who want to become professional fighters have spent years honing their skills in numerous training sessions. It was for these reasons that every warrior was proud of the honor of possessing a sword.

- hilt - a set of components: handle, crosspiece and pommel. Depending on whether the hilt was open or not, the degree of finger protection was determined;

- blade - the warhead of a gun with a narrowed end;

- pommel - the top of a weapon, made of heavy metal. Served to balance weight, sometimes decorated with additional elements;

- handle - an element made of wood or metal for holding a sword. Often, the surface was made rough so that the weapon would not slip out of the hands;

- guard or cross - arose during the development of fencing art and made it possible to protect hands in battle;

- blade - the cutting edge of the blade;

- tip.

General differentiation of swords

Regarding the topic of determining the varieties of this weapon, we cannot ignore scientific works researcher from England E. Oakeshott. It was he who introduced the classification of swords and grouped them by time periods. IN general concept Two groups of types of medieval and later swords can be distinguished:

By lenght:

- short sword - blade 60-70 cm, fighters wore it on their belt on the left side. Suitable for close range combat;

- a long sword - its wedge was 70-90 cm; in battles, as a rule, it was carried in the hands. It was universal for fights on the ground and on horseback;

- cavalry sword. The length of the blade is more than 90 cm.

By weight of the implement and type of handle:

- a one-handed sword is the lightest, about 0.7 - 1.5 kg, which makes it possible to operate with one hand;

- bastard sword or “bastard sword” - the length of the handle did not allow both hands to be placed freely, hence the name. Weight about 1.4 kg, size 90 cm;

- two-handed sword - its weight was from 3.5 to 6 kg, and its length reached 140 cm.

Despite the general classification of species, the sword is more of an individual weapon and was created taking into account the physiological characteristics of the warrior. Therefore, it is impossible to find two identical swords.

The weapon was always kept in a sheath and attached to a saddle or belt.

The formation of the sword in antiquity

In early antiquity, bronze steel was actively used in the creation of blades. This alloy, despite its ductility, is distinguished by its strength. The swords of this time are notable for the following: bronze blades were made by casting, which made it possible to create various shapes. In some cases, for greater stability, stiffening ribs were added to the blades. In addition, copper does not corrode, which is why many archaeological finds retain their beautiful appearance to this day.

For example, in the Adygea Republic, during excavations of one of the mounds, a sword was found, which is considered one of the most ancient and dates back to 4 thousand BC. According to ancient customs, during burial, his personal valuables were placed in the mound along with the deceased.

The most famous swords of that time:

- the sword of hoplites and Macedonians “Xiphos” - a short weapon with a leaf-shaped wedge;

- the Roman weapon “Gladius” - a 60 cm blade with a massive pommel, effectively delivered piercing and slashing blows;

- ancient German “Spata” – 80-100 cm, weight up to 2 kg. The one-armed sword was widely popular among the German barbarians. As a result of the migration of peoples, it became popular in Gaul and served as the prototype for many modern swords.

- “Akinak” is a short piercing and cutting weapon, weighing about 2 kg. The crosspiece is made in a heart shape, the pommel is in the shape of a crescent. Recognized as an element of Scythian culture.

The rise of the sword in the Middle Ages

The Great Migration of Peoples, the seizure of Roman lands by the Goths and Vandals, the raids of barbarians, the inability of the authorities to govern a vast territory, the demographic crisis - all this ultimately provoked the fall of the Roman Empire at the end of the 5th century and marked the formation of a new stage in World History. Humanists subsequently gave it the name “Middle Ages.”

Historians characterize this period as “dark times” for Europe. The decline of trade, the political crisis, and the depletion of land fertility invariably led to fragmentation and endless internecine strife. It can be assumed that it was these reasons that contributed to the flourishing of edged weapons. Particularly noteworthy is the use of swords. The barbarians of Germanic origin, being outnumbered, brought with them the Spata swords and contributed to their popularization. Such swords existed until the 16th century; later, they were replaced by swords.

The diversity of cultures and the disunity of the settlers have significantly reduced the level and quality martial art. Now battles took place increasingly in open areas without the use of any defensive tactics.

If in the usual sense, combat equipment war consisted of equipment and weapons, then in the early Middle Ages, the impoverishment of handicrafts led to a shortage of resources. Only elite troops owned swords and rather meager equipment (chain mail or plate armor). According to historical data, armor was practically absent during that period.

A type of sword in the era of the Great Invasions

Different languages, culture and religious views Germanic settlers and local Romans invariably led to negative relations. The Romano-Germanic conflict strengthened its position and contributed to new invasions of Roman lands by France and Germany. The list of those wishing to take possession of the lands of Gaul, alas, does not end there.

The Huns' invasion of Europe under the leadership of Attila was catastrophically destructive. It was the Huns who laid the foundation for the “Great Migration”, mercilessly crushing the lands one after another, the Asian nomads reached the Roman lands. Having conquered Germany, France, and Northern Italy along the way, the Huns also broke through the defenses in some parts of the Roman border. The Romans, in turn, were forced to unite with other nations to maintain the defense. For example, some lands were given to the barbarians peacefully in exchange for an obligation to guard the borders of Gaul.

In History, this period was called the “Era of Great Invasions.” Each new ruler sought to make his contribution to the modifications and improvements of the sword; let’s look at the most popular types:

The Merovingian royal dynasty began its reign in the 5th century and ended in the 8th century, when the last representative of this family was dethroned. It was people from the great Merovingian family who made a significant contribution to the expansion of the territory of France. From the middle of the 5th century, the king of the French state (later France), Clovis I, pursued an active policy of conquest in the territory of Gaul. Great importance was paid to the quality of the tools, which is why swords of the Merovingian type arose. The weapon evolved in several stages, the first version, like the ancient German spatha, did not have a point, the end of the blade was uncut or rounded. Often such swords were lavishly decorated and were available only to the upper classes of society.

Main characteristics of the Merovingian weapon:

- blade length -75 cm, weight about 2 kg;

- the sword was forged from different types of steel;

- a wide fuller of small depth ran on both sides of the sword and ended 3 cm from the tip. The appearance of a fuller in the sword significantly lightened its weight;

- the hilt of the sword is short and has a heavy pommel;

- the width of the blade almost did not narrow, which made it possible to deliver cutting and chopping blows.

Everyone famous king Arthur existed precisely in this era, and his sword, possessing unimaginable power, was Merovingian.

The Vikings of the noble Carolingian family came to power in the 8th century, dethroning the last descendants of the Merovingian dynasty, thereby ushering in the “Viking Age,” otherwise known as the “Carolingian Era” in France. Many legends were told about the rulers of the Carolingian dynasty at that time, and some of them are known to us to this day (for example, Pepin, Charlemagne, Louis I). In folk legends, the swords of kings are also most often mentioned. I would like to tell one of the stories that is dedicated to the formation of the first king Pepin the Short of the Carolingians:

Being short, Pepin received the name "Short". He became famous as a brave soldier, but people considered him unworthy to take the place of king because of his height. One day, Pepin ordered to bring a hungry lion and a huge bull. Of course, the predator grabbed the bull’s neck. Future king He invited his mockers to kill the lion and free the bull. People did not dare to approach the ferocious animal. Then Pepin took out his sword and cut off the heads of both animals in one fell swoop. Thus, proving his right to the throne and winning the respect of the people of France. So Pepin was proclaimed king, dethroning the last Merovingian.

Pepin's follower was Charlemagne, under whom the French state received the status of an Empire.

Wise politicians of the famous family continued to strengthen the position of France, which naturally affected weapons. The Carolingian sword, otherwise known as the Viking sword, was famous for the following:

- blade length 63-91 cm;

- one-handed sword weighing no more than 1.5 kg;

- lobed or triangular pommel;

- sharp blade and sharpened point for chopping blows;

- deep bilateral valley;

- short handle with a small guard.

Carolingians were mainly used in foot battles. Possessing grace and light weight, it was a weapon for noble representatives of the Vikings (priests or tribal leaders). Simple Vikings more often used spears and axes.

Also, the Carolingian Empire imported its swords into Kievan Rus and contributed to a significant expansion of the weapons arsenal.

The improvement of the sword at every historical stage played a significant role in the formation of a knight's weapon.

3. Romanov (knightly) sword

Hugo Capet (aka Charles Martell) is an abbot, the first king elected following the death of the last descendant of the Carolgins in the 8th century. It was he who was the progenitor of a large dynasty of kings in the Frankish Empire - the Capetians. This period marked by many reforms, for example the formation feudal relations, a clear hierarchy appeared in the structure of the board. New changes also gave rise to conflicts. At this time, the largest religious wars took place, which began with the First Crusade.

During the reign of the Capetian dynasty (approximately the beginning - mid-6th century), the formation of the knightly sword, also known as the “sword for weapons” or “Romanesque”, began. This sword was a modified version of the Carolingian, and met the following characteristics:

- blade length was 90-95 cm;

- significant narrowing of the edges, which made it possible to deliver more accurate blows;

- reduced monolithic pommel with rounded edge;

- a curved handle measuring 9-12 cm, this length enabled the knight to protect his hand in combat;

It is worth noting that the listed changes to the components of the hilt made it possible to fight while riding a horse.

Popular knight swords:

Gradually, the weapon evolved from one-handed spathas to two-handed swords. The peak of popularity of wielding a sword with two hands occurred during the era of chivalry. Let's consider the most known species:

“” is a wavy sword with a flame-shaped blade, a kind of symbiosis of a sword and a saber. Length 1.5 meters, weight 3-4 kg. He was distinguished by his particular cruelty, because with his bends he struck deeply and left lacerated wounds for a long time. The church protested against the flamberge, but nevertheless it was actively used by German mercenaries.

Chivalry as a Privilege

Chivalry arose in the 8th century and is closely related to the emergence of the feudal system, when foot soldiers were retrained as mounted troops. Under religious influence, knighthood was a titled status of nobility. Being a good strategist, Charles Martell distributed church lands to his compatriots, and in return demanded horse service or payment of a tax. In general, the vassalage system was rigidly and hierarchically structured. In addition, obtaining such land limited human freedom. Those who wanted to be free received the status of vassal and joined the ranks of the army. In this way the knightly cavalry was assembled for Crusade.

To obtain the desired title, the future knight began training from an early age. By about the age of seven, his warriors needed to master and improve fighting techniques; by the age of twelve, he became a squire, and by the time he came of age, a decision was made. The boy could be left at the same rank or knighted. In any case, serving the knightly cause was equated with freedom.

Knight's military equipment

The progressive development of handicrafts contributed not only to the modernization of tools, but also to military equipment in general; now such attributes as protective shields and armor appeared.

Simple warriors wore armor made of leather for protection, and noble troops used chain mail or leather armor with metal inserts. The helmet was constructed on the same principle.

The shield was made of durable wood 2 cm thick, covered with leather on top. Sometimes metal was used to enhance protection.

Myths and speculation about swords

The history of the existence of such a weapon is full of mysteries, which is probably why it remains interesting today. Over the course of many centuries, many legends have formed around the sword, some of which we will try to refute:

Myth 1. The ancient sword weighed 10-15 kg and was used in battle as a club, leaving opponents shell-shocked. This assertion has no basis. Weight ranged from approximately 600 grams to 1.4 kg.

Myth 2. The sword did not have a sharp edge, and like a chisel it could break through protective equipment. Historical documents contain information that the swords were so sharp that they cut the victim into two parts.

Myth 3. Steel was used for European swords Bad quality. Historians have established that since ancient times, Europeans have successfully used various metal alloys.

Myth 4. Fencing was not developed in Europe. A variety of sources claim the opposite: for many centuries, Europeans have been working on fighting tactics, in addition, most techniques are focused on the dexterity and speed of the fencer, and not on brute strength.

Despite different versions the origin and development of the sword in history, one fact remains unchanged - its rich cultural heritage and historically important significance.

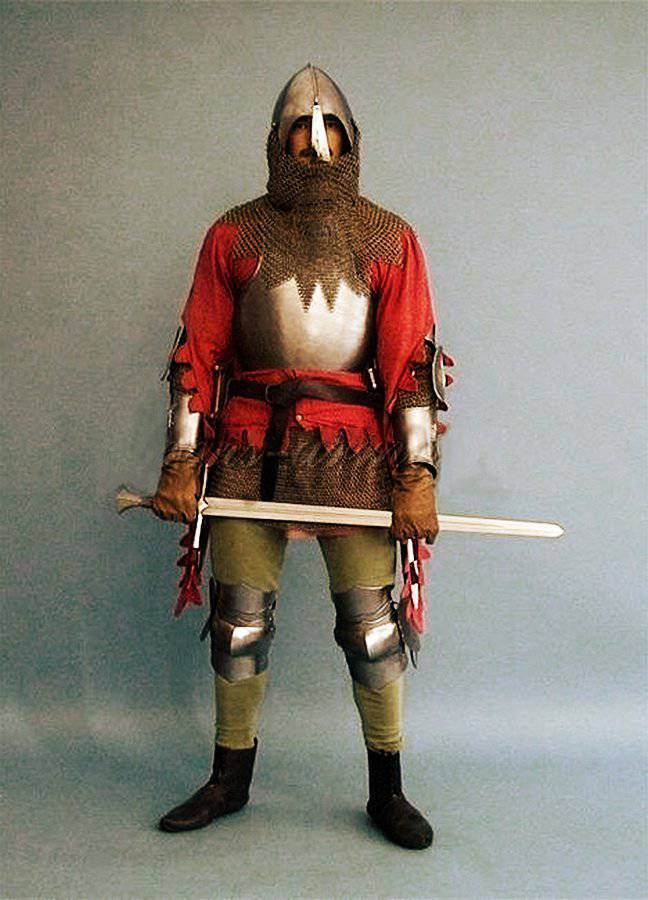

In this article, in the most general outline The process of development of armor in Western Europe in the Middle Ages (VII - late XV centuries) and at the very beginning of the early modern period (early XVI century) is considered. The material is provided with a large number of illustrations for a better understanding of the topic. Most of text translated from English.

Mid-VIIth - IX centuries. Viking in a Vendel helmet. They were used mainly in Northern Europe by the Normans, Germans, etc., although they were often found in other parts of Europe. Very often has a half mask covering top part faces. Later evolved into the Norman helmet. Armor: short chain mail without a chain mail hood, worn over a shirt. The shield is round, flat, medium in size, with a large umbon - a metal convex hemispherical plate in the center, typical of Northern Europe of this period. On shields, a gyuzh is used - a belt for wearing the shield while marching on the neck or shoulder. Naturally, horned helmets did not exist at that time.

X - beginning of XIII centuries. Knight in a Norman helmet with rondache. An open Norman helmet of a conical or ovoid shape. Usually,

A nasal plate is attached in front - a metal nasal plate. It was widespread throughout Europe, both in the western and eastern parts. Armor: long chain mail to the knees, with sleeves of full or partial (to the elbows) length, with a coif - a chain mail hood, separate or integral with the chain mail. In the latter case, the chain mail was called “hauberk”. The front and back of the chain mail have slits at the hem for more comfortable movement (and it’s also more comfortable to sit in the saddle). From the end of the 9th - beginning of the 10th centuries. under the chain mail, knights begin to wear a gambeson - a long under-armor garment stuffed with wool or tow to such a state as to absorb blows to the chain mail. In addition, arrows were perfectly stuck in gambesons. It was often used as a separate armor by poorer infantrymen compared to knights, especially archers.

Bayeux Tapestry. Created in the 1070s. It is clearly visible that the Norman archers (on the left) have no armor at all

Chain mail stockings were often worn to protect the legs. From the 10th century a rondache appears - a large Western European shield of knights of the early Middle Ages, and often infantrymen - for example, Anglo-Saxon huskerls. It could have a different shape, most often round or oval, curved and with a umbon. For knights, the rondache almost always has a pointed lower part - the knights used it to cover their left leg. Produced in various versions in Europe in the 10th-13th centuries.

Attack of knights in Norman helmets. This is exactly what the crusaders looked like when they captured Jerusalem in 1099

XII - early XIII centuries. A knight in a one-piece Norman helmet wearing a surcoat. The nosepiece is no longer attached, but is forged together with the helmet. Over the chain mail they began to wear a surcoat - a long and spacious cape of different styles: with and without sleeves of various lengths, plain or with a pattern. The fashion began with the first Crusade, when the knights saw similar cloaks among the Arabs. Like chain mail, it had slits at the hem at the front and back. Functions of the cloak: protecting the chain mail from overheating in the sun, protecting it from rain and dirt. Rich knights, in order to improve protection, could wear double chain mail, and in addition to the nosepiece, attach a half mask that covered the upper part of the face.

Archer with a long bow. XI-XIV centuries

End of XII - XIII centuries. Knight in a closed sweatshirt. Early pothelmas were without facial protection and could have a nose cap. Gradually the protection increased until the helmet completely covered the face. Late Pothelm is the first helmet in Europe with a visor that completely covers the face. By the middle of the 13th century. evolved into topfhelm - a potted or large helmet. The armor does not change significantly: still the same long chain mail with a hood. Muffers appear - chain mail mittens woven to the houberk. But they did not become widespread; leather gloves were popular among knights. The surcoat somewhat increases in volume, in its largest version becoming a tabard - a garment worn over armor, sleeveless, on which the owner’s coat of arms was depicted.

King Edward I Longshanks of England (1239-1307) wearing an open sweatshirt and tabard

First half of the 13th century. Knight in topfhelm with targe. Topfhelm is a knight's helmet that appeared at the end of the 12th - beginning of the 13th century. Used exclusively by knights. The shape can be cylindrical, barrel-shaped or in the shape of a truncated cone, it completely protects the head. The tophelm was worn over a chainmail hood, under which, in turn, a felt liner was worn to cushion blows to the head. Armor: long chain mail, sometimes double, with a hood. In the 13th century. chain mail-brigantine armor appears as a mass phenomenon, providing stronger protection than just chain mail. Brigantine is armor made of metal plates riveted on a cloth or quilted linen base. Early chain mail-brigantine armor consisted of breastplates or vests worn over chain mail. The shields of the knights, due to the improvement by the middle of the 13th century. protective qualities of armor and the appearance of fully closed helmets, significantly decrease in size, turning into a targe. Tarje is a type of shield in the shape of a wedge, without a umbon, actually a version of the teardrop-shaped rondache cut off at the top. Now knights no longer hide their faces behind shields.

Brigantine

Second half of the XIII - beginning of the XIV centuries. Knight in topfhelm in surcoat with aylettes. Specific feature Topfhelms have very poor visibility, so they were used, as a rule, only in spear clashes. Topfhelm is poorly suited for hand-to-hand combat due to its disgusting visibility. Therefore, the knights, if it came to hand-to-hand combat, threw him down. And so that the expensive helmet would not be lost during battle, it was attached to the back of the neck with a special chain or belt. After which the knight remained in a chain mail hood with a felt liner underneath, which was weak protection against the powerful blows of a heavy medieval sword. Therefore, very soon the knights began to wear a spherical helmet under the tophelm - a cervelier or hirnhaube, which is a small hemispherical helmet that fits tightly to the head, similar to a helmet. The cervelier does not have any elements of facial protection; only very rare cerveliers have nose guards. In this case, in order for the tophelm to sit more tightly on the head and not move to the sides, a felt roller was placed under it over the cervelier.

Cervelier. XIV century

The tophelm was no longer attached to the head and rested on the shoulders. Naturally, the poor knights managed without a cervelier. Ayletts are rectangular shoulder shields, similar to shoulder straps, covered with heraldic symbols. Used in Western Europe in the 13th - early 14th centuries. as primitive shoulder pads. There is a hypothesis that epaulettes originated from the Ayletts.

From the end of the XIII - beginning of the XIV centuries. Tournament helmet decorations became widespread - various heraldic figures (cleinodes), which were made of leather or wood and attached to the helmet. Various types of horns became widespread among the Germans. Ultimately, topfhelms fell completely out of use during the war, leaving pure tournament helmets for a spear collision.

First half of the 14th - beginning of the 15th centuries. Knight in bascinet with aventile. In the first half of the 14th century. The topfhelm is replaced by a bascinet - a spheroconic helmet with a pointed top, to which is woven an aventail - a chainmail cape that frames the helmet along the lower edge and covers the neck, shoulders, back of the head and sides of the head. The bascinet was worn not only by knights, but also by infantrymen. There are a huge number of varieties of bascinets, both in the shape of the helmet and in the type of fastening of the visor. various types, with and without a nosepiece. The simplest, and therefore most common, visors for bascinets were relatively flat clapvisors - in fact, a face mask. At the same time, a variety of bascinets with a visor, the Hundsgugel, appeared - the ugliest helmet in Europe, nevertheless very common. Obviously, security at that time was more important than appearance.

Bascinet with Hundsgugel visor. End of the 14th century

Later, from the beginning of the 15th century, bascinets began to be equipped with plate neck protection instead of chainmail aventail. Armor at this time also developed along the path of increasing protection: chain mail with brigantine reinforcement was still used, but with larger plates that could withstand blows better. Individual elements of plate armor began to appear: first plastrons or placards that covered the stomach, and breastplates, and then plate cuirasses. Although, due to their high cost, plate cuirasses were used at the beginning of the 15th century. were available to few knights. Also appearing in large quantities: bracers - part of the armor that protects the arms from the elbow to the hand, as well as developed elbow pads, greaves and knee pads. In the second half of the 14th century. The gambeson is replaced by the aketon - a quilted underarmor jacket with sleeves, similar to a gambeson, only not so thick and long. It was made from several layers of fabric, quilted with vertical or rhombic seams. Additionally, I no longer stuffed myself with anything. The sleeves were made separately and laced to the shoulders of the aketon. With the development of plate armor, which did not require such thick underarmor as chain mail, in the first half of the 15th century. The aketone gradually replaced the gambeson among the knights, although it remained popular among the infantry until the end of the 15th century, primarily because of its cheapness. In addition, richer knights could use a doublet or purpuen - essentially the same aketon, but with enhanced protection from chain mail inserts.

This period, the end of the 14th - beginning of the 15th centuries, is characterized by a huge variety of armor combinations: chain mail, chain mail-brigantine, composite of a chain mail or brigantine base with plate breastplates, backrests or cuirasses, and even splint-brigantine armor, not to mention all kinds of bracers , elbow pads, knee pads and greaves, as well as closed and open helmets with a wide variety of visors. Small shields (tarzhe) are still used by knights.

Looting the city. France. Miniature from the early 15th century.

By the middle of the 14th century, following the new fashion for shortening that spread throughout Western Europe outerwear, the surcoat is also greatly shortened and turns into a zhupon or tabar, which performs the same function. The bascinet gradually developed into the grand bascinet - a closed helmet, round, with neck protection and a hemispherical visor with numerous holes. It fell out of use at the end of the 15th century.

First half and end of the 15th century. Knight in a salad. All further development of armor follows the path of increasing protection. It was the 15th century. can be called the age of plate armor, when they became somewhat more accessible and, as a result, appeared en masse among knights and, to a lesser extent, among infantry.

Crossbowman with paveza. Mid-second half of the 15th century.

As blacksmithing developed, the design of plate armor became more and more improved, and the armor itself changed according to armor fashion, but Western European plate armor always had the best protective qualities. By the middle of the 15th century. the arms and legs of most knights were already completely protected by plate armor, the torso by a cuirass with a plate skirt attached to the lower edge of the cuirass. Also, plate gloves are appearing en masse instead of leather ones. Aventail is being replaced by gorje - plate protection of the neck and upper chest. It could be combined with both a helmet and a cuirass.

In the second half of the 15th century. arme appears - new type knight's helmet XV-XVI centuries, with double visor and neck protection. In the helmet design, the spherical dome has a rigid back and movable face and neck protection from the front and sides, over which a visor attached to the canopy is lowered. Thanks to this design, the armor provides excellent protection both in a spear collision and in hand-to-hand combat. Arme is the highest level of evolution of helmets in Europe.

Arme. Mid-16th century

But it was very expensive and therefore available only to rich knights. Most of the knights from the second half of the 15th century. wore all kinds of salads - a type of helmet that is elongated and covers the back of the neck. Salads were widely used, along with chapelles - the simplest helmets - in the infantry.

Infantryman in chapelle and cuirass. First half of the 15th century

For knights, deep salads were specially forged with full protection of the face (the fields in front and on the sides were forged vertical and actually became part of the dome) and neck, for which the helmet was supplemented with a bouvier - protection for the collarbones, neck and lower part of the face.

Knight in chapelle and bouvigère. Middle - second half of the 15th century.

In the 15th century There is a gradual abandonment of shields as such (due to mass appearance plate armor). Shields in the 15th century. turned into bucklers - small round fist shields, always made of steel and with a umbon. They appeared as a replacement for knightly targes for foot combat, where they were used to parry blows and strike the enemy’s face with the umbo or edge.

Buckler. Diameter 39.5 cm. Beginning of the 16th century.

The end of the XV - XVI centuries. Knight in full plate armor. XVI century Historians no longer date it back to the Middle Ages, but to the early modern era. Therefore complete plate armor- a phenomenon largely of the New Age, rather than the Middle Ages, although it appeared in the first half of the 15th century. in Milan, famous as the center for the production of the best armor in Europe. In addition, full plate armor was always very expensive, and therefore was available only to the wealthiest part of the knighthood. Full plate armor, covering the entire body with steel plates and the head with a closed helmet, is the culmination of the development of European armor. Poldrones appear - plate shoulder pads that provide protection for the shoulder, upper arm, and shoulder blades with steel plates due to their rather large size. Also, to enhance protection, they began to attach tassets - hip pads - to the plate skirt.

During the same period, the bard appeared - plate horse armor. They consisted of the following elements: chanfrien - protection of the muzzle, critnet - protection of the neck, peytral - protection of the chest, crupper - protection of the croup and flanshard - protection of the sides.

Full armor for knight and horse. Nuremberg. Weight (total) of the rider’s armor is 26.39 kg. The weight (total) of the horse's armor is 28.47 kg. 1532-1536

At the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th centuries. two mutually opposite processes take place: if the armor of the cavalry is increasingly strengthened, then the infantry, on the contrary, is increasingly exposed. During this period, the famous Landsknechts appeared - German mercenaries who served during the reign of Maximilian I (1486-1519) and his grandson Charles V (1519-1556), who retained for themselves, at best, only a cuirass with tassets.

Landsknecht. The end of the 15th - first half of the 16th centuries.

Landsknechts. Engraving from the early 16th century.

Putio War Dagger soldiers wore it on their belt near their left hip. Often his iron scabbard was inlaid with enamel. Images of soldiers with such daggers have been found since the 1st century BC. to 1st century AD This suggests that the dagger was not the main weapon.

Armor, consisting of iron plates, were common from the 1st to the 3rd centuries and predated the cuirass. Such armor partially replaced chain mail and scaly armor. The plates were connected from the inside with leather straps, and from the outside with bronze fasteners.

The biggest were two-handed swords (~1300). They were used by medieval infantry. This huge sword was probably intended for ceremonies, since it is too heavy for combat.

Second two-handed sword called claymore(~1620). It was the weapon of the Scottish Highlanders in the 15th - 17th centuries. Its name comes from the Gaelic expression for "great sword".

This African Throwing Knife from Zaire ( West Africa). In flight, the knife rotates around its center of gravity and wounds the enemy, no matter which end the blow lands on.

Jambia(above) - a dagger of Arabic origin - used in the Middle East and India as a military and ceremonial weapon.

Knife bracelet with a razor-sharp blade worn on the wrist. The knife-bracelet depicted below belonged to the Saka tribe (Kenya). The sharp blade is covered with a cover.

This one is lightweight and durable solid forged bib(~1620) by the famous Italian gunsmith is a technically perfect plate armor. Its shape resembles a tunic - a narrow jacket of the 16th century.

Plate Gauntlets(~1580) protect hands and wrists. This glove from Northern Germany is an example of the fine art of gunsmiths.

Plate sabots(~1550) were supposed to provide freedom of movement. Like a gauntlet, it consisted of movable plates.

Helmet protected the knight's head. This full-face helmet follows the contours of the face and is connected to a throat guard that covers the neck.

Necklace- starting from the 13th century, such necklaces were worn on all types of armor to protect the neck.

Cuirass called armor that covers the upper part of the body. It consists of a breastplate and a backrest, connected by straps. A legguard is attached to the hem of the bib, protecting the stomach and upper thighs.

The shoulder was covered with a special plate - shoulder pad. Protected his hand below bracer With elbow pad in the middle.

Protected the thigh headdress, and the lower leg - greave. The set of plates covering the knee was called knee pad.

From the beginning of the 13th century pot-shaped helmets worn by crusaders and other European knights. The helmet is reinforced with crossed metal strips.

From the middle of the 14th century, they met more often in tournaments pot-shaped helmets with conical top(~1370). This helmet was probably worn over the bascinet, transferring the main weight to the shoulders.

In the 16th century, the closed helmet spread - armet. It differed from its predecessors in its convex chin and throat cover.

During the battle the horse was protected full horse armor. At the tournament, they were usually limited to one part of it - the forehead. The forehead was a structure made of metal plates that covered the forehead and muzzle of the animal. In the middle there was a shield with a protruding spike.

The second stage of the tournament was close combat. It used auxiliary weapons - for example, such a heavy mace ( shestoper).

The plate that protected the left glove was called in French manifer("iron hand"). It was important detail armor, since they held a shield or auxiliary weapon with their left hand.

Knife kukri - traditional weapons Gurkhas (Nepal). The kukri is usually used to cut a path through the jungle, but the heavy curved blade of a knife can become a deadly weapon.

On the recommendation service www.site, only registered users can comment and leave reviews. An authorized user can also mark books, films and other posts. Keep a record of books read and films watched. Add posts to favorites and have quick access to them.