The basics of the bayonet attack of the Russian soldier were taught in the days of Alexander Suvorov. Many people today are well aware of his phrase, which has become a proverb: "a bullet is a fool, a bayonet is a fine fellow." This phrase was first published in the manual on combat training of troops, prepared by the famous Russian commander and published under the title "Science of Victory" in 1806. For many years to come, the bayonet attack became a formidable weapon of the Russian soldier, and there were not so many people willing to engage in hand-to-hand combat with it.

In his work "The Science of Victory" Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov called on soldiers and officers to efficiently use the available ammunition. Not surprising when you consider that it took a lot of time to reload muzzle-loading weapons, which was a problem in itself. That is why the renowned commander urged the infantry to shoot accurately, and at the time of the attack, use the bayonet as efficiently as possible. Smoothbore guns of that time were never considered a priori rapid-fire, so a bayonet attack in battle was of great importance - a Russian grenadier could kill up to four opponents during a bayonet charge, while hundreds of bullets fired by ordinary infantrymen flew into milk. The bullets and guns themselves were not as effective as modern small arms, and their effective range was seriously limited.

For a long time, Russian gunsmiths simply did not create mass small arms without the possibility of using a bayonet with them. The bayonet was the infantry's faithful weapon in many wars, the Napoleonic wars were no exception. In battles with French troops, the bayonet more than once helped Russian soldiers gain the upper hand on the battlefield. The pre-revolutionary historian A.I. When his comrades died in battle, Leonty continued to fight alone. In battle, he broke his bayonet, but continued to fight off the enemy with the butt. As a result, he received 18 wounds and fell among the French killed by him. Despite his wounds, Korennoy survived and was taken prisoner. Struck by the courage of the warrior, Napoleon later ordered the release of the brave grenadier from captivity.

Russian tetrahedral needle bayonet for the Mosin rifle

Recalling their European campaigns, the Wehrmacht soldiers, in conversations with each other or in letters sent to Germany, voiced the idea that those who did not fight the Russians in hand-to-hand combat did not see a real war. Artillery shelling, bombing, skirmishes, tank attacks, marches through impassable mud, cold and hunger could not be compared with fierce and short hand-to-hand fights, in which it was extremely difficult to survive. They especially remembered the fierce hand-to-hand fighting and close combat in the ruins of Stalingrad, where the struggle was literally for individual houses and floors in these houses, and the path traveled in a day could be measured not only by meters, but also by the corpses of dead soldiers.

During the Great Patriotic War, the soldiers and officers of the Red Army were deservedly known as a formidable force in hand-to-hand combat. But the experience of the war itself demonstrated a significant decrease in the role of the bayonet during hand-to-hand combat. Practice has shown that Soviet soldiers used knives and sapper shovels more efficiently and successfully. The increasing distribution of automatic weapons in the infantry also played an important role. For example, submachine guns, which were massively used by Soviet soldiers during the war, did not receive bayonets (although they were supposed to), practice showed that short bursts at close range were much more effective.

RUSSIAN BAYONET

Bayonet fighting is one of the types of close combat, during which the bayonet is used as a piercing-cutting object, and the butt is used as a striking object. Bayonet fighting is based on the same principles as for fencing.

We can say with full confidence that the idea of creating a combined weapon appeared a very long time ago. But its most popular form eventually became the halberd.

combining weapons such as ax, spear and hook. However, most of the development of combined weapons occurred during the development of firearms.

It was the complexity and duration of reloading that required additional equipment. In many museums around the world, a large number of such weapons have been preserved - this is a sword-pistol, an ax-pistol, a shield-pistol, a cane-gun, a knife-pistol, an ink-well pistol, a halberd arquebus and many others. However, the bayonet itself appeared much later.

According to legend, the bayonet was invented in the 17th century in France, in the city of Bayonne, hence the name - bayonet. The first copies of it were lance tips with a shortened shaft, which was inserted into the barrel for further combat. In order to introduce this weapon for the entire army, it was decided to demonstrate it to Louis XIV. However, the imperfect design led the king to order the bayonets to be banned as impractical weapons.

Fortunately, the same demonstration was attended by a captain with a very famous surname d'Artagnan, who managed to convince Louis. And so a new type of weapon appeared in service with the French army. Then its use spread to other European states. In 1689, the bayonet appeared in service with the military in Austria.

Petrovsky charter

At the beginning of the 18th century, Peter I made the practice of bayonet fighting techniques a statutory law of the army. The brutal defeat at Narva served as the starting point for the extensive training of army and navy personnel in hand-to-hand combat, and the introduction of fencing in educational institutions. In 1700, with the direct participation of Peter, the first official document regulating the combat training of the Russian infantry "Short ordinary training" was developed. In it, special attention was paid to bayonet combat using baginets (a kind of bayonet). Moreover, if in the Western armies baguettes were used primarily as a defensive weapon, in the "Brief Ordinary Training" the idea of an offensive use of a bayonet was developed.

Petrovsky grenadier

The preparation of soldiers for bayonet combat occupied a significant place in the "Military Regulations", which was put into effect in 1716. Peter 1 demanded that officers organize and conduct training of subordinates in such a way that "the soldiers get used to it, as in the battle itself." At the same time, great importance was attached to individual training: "It is necessary for the officers to observe with diligence for each soldier, so that they can live in the best possible way."

Soon, one small innovation was introduced - in addition to the trimmed lance, they began to attach a tube to the barrel. This is how the type of weapon that the Russians call a bayonet appeared. For a very long period of time, this weapon was used as a means of protecting infantrymen from cavalry.

The revolution in the use of the bayonet was made by A.V. Suvorov, who understood that only by seriously mastering the skills of a bayonet fight, Russian soldiers could defeat the Turks in hand-to-hand combat.

It was A. Suvorov who made the bayonet a means of attack, emphasizing its obvious advantages in close combat. This decision was caused by a number of objective reasons.

With a relatively low level of military equipment at that time, aimed fire from smooth-bore weapons could be fired no further than 80-100 steps. This distance was covered by running in 20-30 seconds. During such a period of time, the enemy, as a rule, managed to shoot only once. Therefore, a swift attack, which turned into a swift bayonet strike, was Suvorov's main means of achieving victory in battle. He said that "the enemy has the same hands, but they just don't know the bayonet."

The soldiers were trained in action with bayonets both in the ranks and individually. Before the Italian campaign of 1799, Suvorov, knowing that the Austrians were weak fighters in a bayonet fight, wrote instructions specifically for their army. It gave the following advice: "... and when the enemy approaches thirty steps, the standing army itself moves forward and meets the attacking army with bayonets. Bayonets are held flat with the right hand, and prick with the left. On occasion, it does not interfere with the butt. chest or head. "

"... at a distance of a hundred paces to command: march-march! At this command, people grab their guns with their left hand and rush at the enemy with bayonets shouting" vivat "! butt it. "

The recommendation to stab in the stomach is due to the fact that regular army soldiers (in this case, the French) had thick leather belts on their chests, crossing each other (one for a half-saber, the other for a cartridge bag).

French infantry

It is quite difficult for an experienced fighter to break through such a defense. A blow to the face was also fraught with the risk of a miss, as the opponent could turn his head away. The belly was open and the soldier could not recoil while in the ranks. Suvorov taught to hit the enemy with the first blow, so that the fighter then managed to fend off an attack directed at him. Actions had to be clear and well-coordinated, according to the principle of "prick - protection" and again "prick - protection". At the same time, as can be seen from the above tips, the butt could be widely used. The Russians successfully tried the tactics used against the Turks on the French as well.

Borodino - a great battle.

And in the future, special attention was traditionally paid to bayonet combat in the Russian army.

“If, for example, you sneak, you must do it mentally, because fighting in battle is the first thing, and, most importantly, remember that you need to stab the enemy on a full lunge, in the chest, with a short blow, and pull the bayonet out of his chest shortly ...

Remember: shortly back from the chest, so that he does not grab with his hand ... That's it! R-times - full lunge and p-times - shortly back. Then r-one-two! R-one-two! press your foot shortly, frighten him, the enemy r-one-d-two! "- so, according to the memoirs of the famous journalist Vladimir Gilyarovsky, non-commissioned officer Ermilov," a great master of his craft ", taught the soldiers to bayonet combat. It was in 1871, when Gilyarovsky served as a volunteer in the army.

Instructor Ermilov, like Suvorov, also loved figurative and intelligible expressions:

“And whoever has the wrong fighting stance, Ermilov loses his temper:

What grumbled you? The belly, or something, hurts, gray-footed! You hold on at ease, like a general in the carriage collapsed, and you, like a woman over a milk heap ... A goose on a wire!

The method of striking "full lunge, in the chest, with a short blow" at that time was a relative novelty in the Russian army, because even during the years of the Crimean War (1853-1856), Russian soldiers beat them with a bayonet in a different way. The historian writer Sergeev-Tsensky described this technique as follows:

"Russian soldiers were taught to beat with a bayonet only in the stomach and from top to bottom, and when hitting, lower the butt, so that the bayonet went up, twisting the insides: it was useless to even take such wounded to the hospital."

Indeed, what use could there be from a hospital after that ...

It was necessary to abandon such an effective method of bayonet fighting under international pressure.

The fact is that in 1864 the first Geneva Convention was signed, which related exclusively to the issues of providing assistance to wounded soldiers. The initiator of the convention was the Swiss public figure Henri Dunant. In 1859, he organized the provision of assistance to the wounded at the Battle of Solferino during the Austro-Italo-French War, which killed 40 thousand killed and wounded. He was also the initiator of the creation of the organization, which later came to be called the Red Cross (Red Crescent) Society. The Red Cross was chosen to be the identification mark of the medics working on the battlefield.

In Russia, the Red Cross Society was created in May 1867 under the name "The Society for the Care of the Wounded and Sick Warriors." It was here that I had to face requests from the international community (mainly in the person of England and France, who had the saddest memories of Russian bayonet attacks during the Crimean War) to abandon the terrible blow to the stomach. As an alternative, the blow to the chest described above was chosen.

Bayonet fighting is a type of fencing, in the technique of which a lot is borrowed from the technique of combat with long-tree weapons. The assertion that the Russian bayonet battle was the best in Europe, although it made everyone sore, is nevertheless true, and this was recognized in any army up to the Second World War.

The main recommendations for bayonet combat at the beginning of the last century were set out in the book by Alexander Lugarr "Guide to fencing with bayonets", published in 1905 after the end of the Russo-Japanese war.

Here are some of the techniques outlined there:

“The soldier strikes while holding the gun at head level or slightly higher.

The butt of the weapon is turned up. The bayonet is aimed at the head, neck or chest; slightly above. Parade against such a blow is performed while holding a gun

with the butt up, leading the enemy's bayonet to the left with the central part of the box.

(It is possible to repulse such a blow with your own bayonet or with the upper part of the gun, holding the weapon with the bayonet up and leading them to a directed blow to the right or left,

while slightly bending the body).

2. The blow is applied from the bottom up, with the knees bent, and directed to the abdomen. They repulse him by turning the gun with a bayonet to the ground, leading the enemy's weapon to the left or right.

3. It is carried out according to the same principle as impact No. 2, but the knees are not bent so much. The bayonet is directed from the bottom up to the head or neck. The parade is carried out with a simple movement of the gun to the side. The attacker's bayonet is taken to the center of the box; the body shifts to the left. (With the upper grip of the gun with the right hand, the same is done, but in the opposite direction. This position is also convenient because it allows the defender to immediately go on the attack).

As we can see, Lugarr does not offer to refuse to hit with a bayonet in the stomach. True, he does not recommend lifting the bayonet in the stomach, "turning the gut". Times are not the same, the humane twentieth century is in the yard ...

The first Russian rifle, which was originally designed as a breech-loading rifle, was a 4.2-line rifle mod. 1868 Gorlov-Gunius system ("Berdan system No. 1").

This rifle was designed by our officers in the United States and was fired without a bayonet. Gorlov, at his discretion, chose a triangular bayonet for the rifle, which was installed under the barrel.

After firing with a bayonet, it turned out that the bullet was moving away from the aiming point. After that, a new, more durable four-sided bayonet was designed (remember that three sides were needed exclusively for muzzle-loading systems). This bayonet, as on previous rifles, was placed to the right of the barrel to compensate for the derivation.

Such a bayonet was adopted for the 4.2-line infantry rifle mod. 1870 g.

("Berdan system No. 2") and, slightly modified, to the dragoon version of this rifle. And then very interesting attempts began to replace the needle bayonet with a cleaver bayonet. Only through the efforts of the best Russian minister of war in the entire history of our state, Dmitry Alekseevich Milyutin, was it possible to defend the excellent Russian bayonet. Here is an excerpt from D.A. Milyutin for March 14, 1874: “... the question of replacing bayonets with cleavers was again raised ... following the example of the Prussians. Three times this issue has already been discussed by competent persons: everyone unanimously gave preference to our bayonets and refuted the sovereign's assumptions that bayonets should adhere to rifles only at a time when the need to act with cold weapons would be presented. And despite all the previous reports in this sense, the issue is raised again for the fourth time. With a high probability, one can assume here the insistence of Duke Georg Mecklenburg-Strelitzky, who cannot allow anything to be better here than in the Prussian army. "

Here it is time to remember another interesting feature of the Russian bayonet, its sharpening. It is very often called a screwdriver. And even very serious authors write about the dual purpose of the bayonet, they say, they can stab the enemy and unscrew the screw. This is, of course, nonsense.

For the first time, sharpening the blade of a bayonet not on the point, but on a plane similar to the tip of a screwdriver, appeared on newly manufactured bayonets for the Russian rapid-fire 6-line rifle mod. 1869 ("Krnka system") and tetrahedral bayonets to the infantry 4.2-line rifle mod. 1870 ("Berdan system No. 2"). Why was she needed? Obviously do not loosen the screws. The fact is that the bayonet must not only be "stuck" into the enemy, but also quickly removed from him. If a bayonet sharpened on a point pierced the bone, then it was difficult to extract it, and a bayonet sharpened on a plane seemed to go around the bone without getting stuck in it.

By the way, another curious story is connected with the position of the bayonet relative to the barrel. After the Berlin Congress of 1878, during the withdrawal of its army from the Balkans, the Russian Empire presented the young Bulgarian army with over 280 thousand 6-line rapid-fire rifles mod. 1869 "Krnka system" mainly with bayonets arr. 1856 But a lot of bayonets for rifled guns mod. 1854 and earlier smoothbore. These bayonets were normally adjacent to the "Krnk", but the bayonet blade was located not to the right, as expected, but to the left of the barrel. It was possible to use such a rifle, but accurate shooting from it without re-shooting was impossible. And besides, this position of the bayonet did not reduce the derivation. The reasons for this incorrect placement were different slots in the tubes that determine the method of bayonet attachment: arr. 1856 was fixed on the front sight, and bayonets to the systems of 1854 and earlier were fixed on the under-barrel "bayonet rear sight"

Privates of the 13th Infantry Belozersk Regiment in combat uniform with full marching equipment and a Berdan No. 2 rifle with a whipped bayonet. 1882 g

Privates of the 13th Infantry Belozersk Regiment in combat uniform with full marching equipment and a Berdan No. 2 rifle with a whipped bayonet. 1882 g

Private Sophia infantry regiment with muzzle-loading rifle mod. 1856 with an attached three-edged bayonet and a clerk of the Divisional Headquarters (in full dress). 1862 g.

And so the years passed, and the era of store-bought weapons began. The Russian 3-line rifle already had a shorter bayonet. The overall length of the rifle and bayonet was shorter than that of previous systems. The reason for this was the changed requirements for the total length of the weapon, now the total length of the rifle with a bayonet had to be higher than the eyes of a soldier of average height.

The bayonet still remained attached to the rifle, it was believed that the soldier should shoot accurately, and when the bayonet was attached to the rifle, which was shot without it, the aiming point changed. That is not important at very close distances, but at distances of about 400 steps it was already impossible to hit the target.

The Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) showed a new battle tactics, and it was surprisingly noticed that Japanese soldiers, by the time of hand-to-hand combat, still managed to fasten their bladed bayonets to their Arisaki.

Soviet bayonets at the beginning of the Great Patriotic War. Top down:

bayonet for 3-line rifle mod. 1891, bayonet for 3-line rifle mod. 1891/30, bayonet for ABC-36, bayonet for SVT-38, bayonets for CBT-40 of two types

Sheathed bayonets. Top - down: bayonet to CBT-40, bayonet to SVT-38, bayonet to ABC-36

Sheathed bayonets. Top - down: bayonet to CBT-40, bayonet to SVT-38, bayonet to ABC-36

Speaking about Russian blades of the 18th – 19th centuries - in particular, about melee weapons, it is impossible not to dwell on bayonets. “A bullet is a fool, a bayonet is a fine fellow” - this legendary saying of Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov has gone down in history forever as a laconic description of the tactics of an infantry attack of that time. But when did the bayonet itself appear?

The prototype of the bayonet was a baguette (bayonet) - a dagger or a strong knife with a handle tapering to the edge, which was inserted into the barrel of a gun, turning it into a kind of spear or spear. By the way, it was the shortened spear that became the first baguette, which was originally invented by hunters. Indeed, hunting for a large and dangerous animal, in the distant past, hunters had to carry, in addition to a gun, a spear (to finish off a wounded animal with a shot or to repel its attack on a hunter). And this is an extra and cumbersome load. It is much more convenient to have a detachable blade or a powerful tip that fits over the barrel of a gun.

Baginet is a prototype bayonet.

The first baguettes appeared in Great Britain in 1662 (this date marks the first mention of baguettes as part of the armament of the English regiment). According to various sources, English baguettes had blades ranging in length from 10 inches to 1 foot.

The baguette could have a flat or faceted shape, as a rule, it did not have a guard (just a thickening or a simple crosshair). The handle was made of bone, wood, or metal.

In France, baguinets appeared somewhat earlier, since the British initially acquired them from the French. The French themselves are credited with the invention of this device (some historians indicate 1641 as the date of the creation of the bayonet in the vicinity of the city of Bayonne). The baguette was adopted by the French army in 1647.

The baginette esponton was in service in the 18th century with Saxon officers.

Baguinets have also been used in Russia, but very little is known about their use. The archival documents contain data that baguettes were put into service in 1694 and up to 1708-1709. the Russian infantry used one-sided baguettes along with the fuse. Russian baguettes had a guard in the form of a bow that did not reach the handle (so as not to interfere with sticking into the barrel of a gun). The length of Russian baguinets ranged from 35 to 55 cm.

The bayonet (from the Polish sztych) replaced the baguette. The French began to use improved baguinets in the form of blades with a tube instead of a handle, which were mounted on the barrels of guns from above and allowed firing and loading with a sided blade weapon. For the first time, French troops were equipped with bayonets in 1689. Following the French, the Prussians and Danes switched to bayonets. In Russia, bayonets began to be used in 1702, and the transition to bayonets and the abandonment of baguettes was completed in 1709.

Bayonets are divided into removable and non-removable; faceted, round, needle and flat. Flat, that is, bladed bayonets are divided into bayonet-knives, bayonet-epee, bayonet-daggers, bayonet-cleavers, scimitar bayonets. Such edged weapons can be used separately from firearms and have devices for attaching to the barrels of small arms.

Faceted and round needle bayonet

A faceted bayonet looks like a sharp blade with several edges (usually three or four) with a tube instead of a handle, which is put on the barrel. Initially, the faceted bayonet had three edges. A little later, tetrahedral bayonets appeared, as well as T-bayonets (in section they looked like the letter "T"). Sometimes there were five- and hexagonal ones, but soon the increase in the number of faces turned the faceted bayonet into a round one, and models with more than four faces did not take root.

Faceted bayonets with pipes from the Crimean War period from the exposition of the Mikhailovskaya Battery museum complex, Sevastopol: British bayonets at the top, Russian bayonets at the bottom.

At first, the bayonet tube was attached to the barrel simply on a tight fit (holding by friction). In battle, such bayonets often fell from the barrels, could be pulled off by the enemy, and sometimes, due to dirt that got into the attachment point, small arms and a bayonet were very difficult to separate. Around 1740, a bayonet with an L-shaped groove on the attachment tube was created in France, which made it possible to securely fasten the bayonet to the barrel, putting it on so that the front sight passed into the groove (in this case, the sighting front sight acted as a stopper). In the future, this design was slightly modified, but not fundamentally.

The edges of the bayonets could have valleys or not. Some bayonet models had sharp edges (the shape formed when crossing adjacent valleys). Such bayonets could inflict wounds not only with a point, but also with ribs. But their strength was lower, the edges of the edges of the bayonets often crumbled when colliding with enemy bayonets or other solid objects. Russian bayonets had valleys with blunt ribs; only the tip of the bayonet was sharply sharpened. Triangular bayonets were in service with many armies of European countries. Quadrangular bayonets were used in the armies of Russia and France.

Round bayonets were also used in the Russian army. It was at the end of the 18th century. From a report dated 03/27/1791 addressed to His Serene Highness Prince Potemkin: “This March 25 was received from Mr. Shter-Kriegs-Commissar, Chevalier Turchaninov in Your Highness, the Yekaterinoslav Grenadier Regiment entrusted with sabers for chief officers eighty-six, and for non-commissioned officers and grenadier four thousand, round bayonets three thousand five hundred seventy nine ... ". The specified regiment received exactly round bayonets, not faceted ones. A bayonet of this shape is in the VIMAIViVS collection, and it is also listed as an "experimental bayonet" in the reference book edited by A. N. Kulinsky. Also, a gun with a round bayonet is in the Artillery Museum. It is known that round bayonets were in service with the Yekaterinoslav regiment until the end of the reign of Catherine the Great.

Needle-shaped bayonets were preferable during hand-to-hand (bayonet) combat than bladed ones. They practically did not get bogged down in the enemy's body, had a smaller mass and were not cumbersome. Shooting from a rifle with an attached needle-shaped bayonet is always more aimed. However, the needle bayonet is almost impossible to use for other purposes. Therefore, the bladed models of bayonets also had a certain distribution.

A sword bayonet is very similar to a regular faceted bayonet. Such bayonets were in service with the French army (1890). The length of the bayonet-epee blade reached 650 mm. The sword bayonet had a handle and a small guard in the form of a cross. One edge of the cross ended with a ring that was put on the barrel, and the pommel of the handle was adjacent to a special socket with a latch located in the forend of the rifle. Sword bayonets were used by the French for a long time, right up to the First World War. There were several varieties of them: with a triangular and tetrahedral blade, with a T-shaped section, with a forged steel handle, etc. All sword bayonets were equipped with a sheath made of leather or metal.

Sword bayonets became widespread in the Prussian army in the middle of the 18th century. Such models of bayonets assumed dual use: as bayonets in an attached state, and as cleavers - for use separately from guns. By the beginning of the 19th century, the popularity of such bayonets increased and they began to be used in various European countries, in particular in England, where the armament of infantry with bayonets-cleavers became widespread. English cleaver bayonets had brass hilts and double-edged blades. A similar type of cleaver bayonet was used in the years 1850-1860. by the military of the North American States.

Sapper bayonet-cleaver. It was used in a side-by-side position to repel enemy attacks and separately from small arms - for hand-to-hand combat, trenching, clearing passages, cutting palisades.

In Russia, the cleaver bayonet was used in conjunction with the 1780s sample fitting, the 1805 sample fitting and the 1843 sample littikh fitting. At a later time, the cleaver bayonet was supplanted by a needle-shaped bayonet (with rare exceptions - a faceted bayonet).

In the armies of Europe, the bayonet-cleaver quite successfully coexisted and competed with faceted bayonets. For example, in France, in the artillery units, the faceted bayonet was replaced with a cleaver bayonet of the 1892 model. German and Austrian troops used the cleaver bayonet in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Bayonets were also used in Asian countries. A rather curious example: the Type 96 light machine gun was adopted by the Japanese Kwantung army (in the 30s of the twentieth century), and later - Type 99. These machine guns were equipped with bayonets-cleavers. It is not known whether there were cases of effective use of the bayonet for its intended purpose, because the Japanese soldiers of that time did not differ in physical strength, and the machine gun weighed about 10 kg and had decent dimensions. Most likely, the decision to equip the machine gun with a bayonet was made out of respect for the military traditions of Japan (the historically established cult of knives).

Japanese machine gun with an attached bayonet.

In the USSR, the bayonet-cleaver survived "reincarnation": they were equipped with automatic rifles of F.V. Tokarev, S.G. Simonov and V.G. Fedorov. Tokarev's and Simonov's rifles were in service until 1945 (as were bayonets-cleavers for them).

A scimitar bayonet is a special case of a cleaver bayonet. Such models were equipped with a blade that had an angular (very small angle) bend downward at a distance of ½ to ⅔ from the handle. Of course, it was not quite a scimitar, but the design is similar. Such bayonets were produced in France, Great Britain, Japan and other countries. They were completed with a scabbard made of leather or metal.

Towards the end of the 19th century, knife bayonets began to be adopted by the armies of the world. A. N. Kulinsky in his book "Bayonets of the World" gave a definition of a bayonet-knife: ". This is a bayonet, which, separated from a rifle or carbine, can be used as a knife, including for causing damage to the enemy ...". That is, a bayonet-knife is a bayonet that has retained all the functional properties of a combat knife. The appearance of the bayonet-knife is due to the development of small arms: with an increase in range, rate of fire and power, the role of bayonets has sharply decreased. The infantry needed more functional and lighter models.

The first bayonet-knife model 71/84 for the Mauser rifle, Germany.

The first bayonet-knife was created in Germany in 1884. It was developed for the Mauser rifle (sample 1871/84). The bayonet-knife was used in a side-by-side position for a bayonet attack, and in the hand it was also a formidable weapon. In addition, the 71/84 bayonet was used to perform various works in the field. After some time, bayonet knives appeared in many armies of the world. The very first serial bayonet-knife became the prototype for the creation of such models.

Bayonet knives are usually divided into the following types:

- bayonets-knives with one-sided sharpening (single-blade models);

- bayonets-knives with double-edged blades;

- bayonets-knives with double-sided sharpening of the T-shaped blade;

- stiletto bayonets with needle-shaped blades.

A classic device for attaching a bayonet-knife to small arms is a combination "groove-latch-ring", in which the ring is put on the barrel, a special protrusion on the handle is inserted into the groove, and the handle itself is fastened with a latch on the forearm of the weapon with its end part.

Germany has become the world's leading developer and manufacturer of bayonet knives. In Germany, a huge number of bayonet knives were created both for the needs of their army and for third-party customers. There were about a hundred ersatz bayonets of German origin alone. At the beginning of the twentieth century (1905), a very popular model 98/05 was created, many of which have survived to this day. In Russia, bayonet knives were not popular; Russian faceted bayonets with pipes were in use. The creation of bayonet knives was taken care of only under the USSR, but we will talk about this later.

Bayonet 98/05

Concluding the story about bayonets, we note the existence of another interesting group, which includes rare and almost exotic models of bayonets. These are the so-called bayonet instruments. In various years, bayonets-shovels, bayonets-saws, bayonets-scissors, bayonets-machetes, bayonets-bipods and so on were created. Alas, these products did not receive much popularity due to their low efficiency. In this combination, neither a good instrument nor a worthy bayonet was obtained.

At the beginning of the First World War, with the onset of the so-called "trench war", it was discovered that in hand-to-hand combat, in trenches and dugouts, long-barreled firearms and bayonets created for them were not effective. The formidable Russian three-line and German Mauser rifles uselessly pricked the air at a distance of up to two meters, while a compact weapon was required, with a not very large blade adapted for a thrusting blow. The armies of the long-suffering Europe, shaken by the hostilities, began to hastily arm themselves with whatever they could. Germany, armed with blade bayonets and full-fledged bayonet-knives, was in a winning situation. And France, Italy, Great Britain, Russia and others had to adapt and remake various edged weapons. Stilettos were made from trophy bayonets or shortened to the size of a universal hunting knife. The so-called "French nail" was very popular - a piece of steel rod, riveted and pointed on one side and bent into an elongated letter "O" on the other. The primitive handle also served as a kind of brass knuckles.

The French nail is one of the popular home-made products for hand-to-hand combat in the trenches. The bow of the handle served as brass knuckles.

In Russia, due to archaic officials, the adoption of a bladed bayonet knife simply failed. A soldier's dagger of the 1907 model, known as a bebut, came to the rescue (see part II). The experience of the Caucasian campaign was not in vain. From 1907 to 1910, the bebut was adopted by the gendarmerie, the lower ranks of machine-gun crews, the lower ranks of artillery crews, and the lower ranks of horse reconnaissance. With the outbreak of the First World War, a simplified version of the bebut was also made, with a straight blade. Of course, there were not enough daggers to fully support the army. Trophy samples and alterations were used.

Russian infantry soldier's dagger bebut.

Over time, the "peaceful" models of knives have changed and been updated. Shoemaker knives, wood cutting tools (carving) and other professional knives, like hunting knives, have changed little. But folding models appeared, first of all, the so-called penknives. At first they were imported from Sweden, Germany, France, Switzerland. And later, Russian craftsmen began to make very good folding knives. It is noteworthy that many craftsmen lived and created excellent knives in the outback, and not only in St. Petersburg, Moscow or Novgorod, locating their workshops closer to mines and handicrafts. For example, G. Ye. Varvarin from Vorsma made multifunctional knives, outwardly similar to the French "Layol". We note the folding knives from Vachi, the work of the master Kondratov. Well, the name of the master Zavyalov is well known all over the world.

Penknife from Vorsma by Varvarin.

Ivan Zavyalov was a serf of Count Sheremetyev and thanks to his skill, perseverance and natural gift, he was able to start his own business, to achieve the highest level of skill. In 1835 he made several knives for the imperial family. Nicholas I himself was shocked by the elegance and quality of Zavyalov's work, for which he granted him a caftan with gold laces and a monetary reward of 5,000 rubles (a huge amount at that time).

Folding knife made by master Kondratov from Vacha.

Zavyalov made folding pocket knives, table knives and combined devices (knife-fork in one item), the so-called hunting couples (knife and fork for game) and other knives. The master forged the blades himself, and for the handles he used silver, horn, bone, wood. In 1837, he presented the emperor with a set of folding knives, for which he was awarded a gold ring with diamonds. His works were at the level of the products of the best masters of Germany and England. Since 1841, Zavyalov was given the privilege of putting the tsar's coat of arms on his works, later he received a medal at a manufactory exhibition in Moscow, and in 1862 - a medal at an exhibition in London. Duke Maximilian and the Grand Duke of the Russian Empire admired his work. Using the example of one master, we highlighted the level of knife production in Russia in the period of the 19th and early 20th centuries. But Zavyalov was not the only Russian skilled knife-maker of such a high level. The surnames of Khonin, Shchetin, Khabarov and others are well known to collectors and naifomaniacs in Russia. Knife crafts worked and developed in Pavlovskaya Sloboda (now Pavlovo-on-Oka), Zlatoust, Vorsma. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Russia had several powerful centers of blade production and a whole scattering of nugget masters who created real masterpieces.

A characteristic feature of knives with fixed blades made by master Zavyalov is an Archimedes screw on the shank.

In the next chapter, we will dwell in detail on bladed products of the First World War, the Civil and Second World War, Russian and European knives of the period before 1945.

Gulkevich's bayonet

My accidental interest in the bayonet of the Mosin rifle led to an unexpected result - I discovered that this type of simple edged weapon had a rather interesting and difficult fate. The needle tetrahedral bayonet was adopted by the Russian imperial army at the same time as the Mosin rifle back in the 19th century.

It was assumed to carry this bayonet always side-by-side, and therefore the rifle was targeted with a side-mounted bayonet. The advantage of this use of a bayonet was that the rifle was always ready for hand-to-hand combat.

Military experts have calculated during the time when the fighter is adjacent to the bayonet, he could make 6-7 shots. Therefore, in defense, the always sided bayonet of the Mosin rifle was especially valuable - the fighter without ceasefire went over to bayonet combat.

In addition, they believed that the bayonet was a factor reducing the chance of retreat and flight. The fact is that already in the wars of the late 19th century, the number of those killed and wounded with cold weapons was negligible. However, it was the bayonet attack that, in most cases, put the enemy to flight.

Thus, the main role was played not by the actual use of the bayonet, but by the threat of its use. Therefore, a fighter who does not have an effective melee weapon begins to experience uncertainty.

However, no matter how good the long needle bayonet of the Mosinka was, the massive use of shrapnel and machine guns radically changed the nature of the battle.

Already at the beginning of the 20th century, this bayonet did not meet modern requirements. Its main drawback was that the bayonet had to be carried always side by side.

Colonel ON. Gulkevich. He proposed an original bayonet design. His bayonet adjoined the rifle and, due to the hinge, folded with the tip towards the butt.

The bayonet passed the tests - they beat them on the boards for a long time, the bayonet passed the test and was accepted into service. It is often written that Gulkevich's bayonet is experimental, but this cannot be, if the sample is adopted for service, it ceases to be experimental.

Gulkevich was equipped with a bayonet, mainly Cossack units. The feedback from the combat units was rave. Later, weapons designer Fedorov, wrote that Gulkevich's bayonet was discontinued due to the shortcomings identified in it.

It meant that as a result of prolonged wear and shaking, the hinge screw self-loosened. However, it seems to me that the screw is an excuse, the real problem was the lack of production capacity. The Russian industry could not produce even a simple standard bayonet in sufficient quantities, therefore, in the First World War, there were many different ersatz bayonets.

In the most difficult periods of the war, everything was used: captured Mannlichers, Berdanks, Winchesters with Henry's brace, etc.

It is interesting that in the armies of Austria, Germany and France, which used a large number of Mosin rifles, they went the other way - they shot a three-line without a bayonet, and he the bayonet was worn on a belt in a special case. After the First World War, the leadership of Soviet Russia for a long time was not engaged in the modernization of weapons. Hands reached the rifle only at the end of the 20s. The bayonet was also changed. In particular, a latch was made and now the bayonet no longer loosened, held tight and did not interfere with shooting.

Why at this time the release of Gulkevich's bayonets was not resumed in the USSR is a mystery to me. It can be assumed that this was done again for economic reasons.

Why start production of a new bayonet if automatic and self-loading rifles with blade bayonets are being prepared for serial production?

At the end of the 30s, the Soviet designer Tokarev F.V. developed and tested the SVT rifle. She was adopted in service and gradually began to replace her old magazine rifles. In fiction, a lot has been written and is being written to this day that the rifle was unreliable, "lousy", so it was gradually taken out of production.

However, it seems to me that the main the reason for the withdrawal from production of CBT was its high cost. History knows a lot of cases when wonderful models of weapons that were removed from service or were not accepted into service due to their high cost.

SVT suffered the fate of Gulkevich's bayonet - it was declared unreliable because it was not cheap enough.

A little distracted, I want to dwell on the cost of weapons in more detail. Often on the Internet you can read a long list of complaints about the Mosin rifle: heavy, long, does not have at least a half-pistol bend, not the most convenient bolt, trigger, etc.

At the same time, not many people know that even before the First World War, the chief of artillery of the Odessa Military District Lieutenant General N.I. Kholodovsky significantly modernized the Mosin rifle. The experimental specimen was named the Mosin-Kholodovsky rifle.

The weapon possessed remarkable data: it was much shorter, lighter, firing from it was much more accurate. By the way, the bayonet of this rifle was also quite original: made of an alloy with aluminum.

Subsequently, many dreamers from the "French bakers" sighed: if only Kholodovsky's rifle and Gulkevich's bayonet made using Kholodovsky's technology, then Russia would have the best rifle in the world!

But dreamers are dreamers. The Russian industry in the First World War could not cope even with orders for three-line "wartime" with ersatz-bayonets.

However, let's return to the period of the Great Patriotic War. The terrible load on the Soviet industry quickly forced to abandon the production of SVT and resume the mass production of three-rulers arr. 1930 of the year. It was produced with the same constantly worn bayonet, which was already considered obsolete at the beginning of the century.

As it turned out, the shops, supplemented with machine gun pistols, may well satisfy the needs of the front. But the rifle should be shorter and the bayonet should be removable or foldable.

As a result, a competition was announced and out of 8 bayonets the most suitable was the design bayonet. NS. Semina. This bayonet was equipped with a carbine mod. 1938, after which the carbine is called “carbine mod. 1944 ".

I came across information that Gulkevich's bayonet was allegedly presented at the mentioned competition. It is possible that several decades after it was discontinued, it had a chance to return. However, the rifle of the 1930 model was already excessively long, even with a folding bayonet. Therefore, a carbine went into the series.

Now we can only express regret that Gulkevich's bayonet was removed from production in the First World War and did not resume production in 1930, during the modernization of the three-line.

Just in case, I will make a reservation: I am a historian "production worker", not a "iron worker" and this post is not my specialization. And everything I wrote above - I read it on the Internet. Therefore, anyone who provides more accurate material - I will be grateful.

The basics of the bayonet attack of the Russian soldier were taught in the days of Alexander Suvorov. Many people today are well aware of his phrase, which has become a proverb: "a bullet is a fool, a bayonet is a fine fellow."

This phrase was first published in the manual on combat training of troops, prepared by the famous Russian commander and published under the title "Science of Victory" in 1806. For many years to come, the bayonet attack became a formidable weapon of the Russian soldier, and there were not so many people willing to engage in hand-to-hand combat with it.

In his work "The Science of Victory" Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov called on soldiers and officers to efficiently use the available ammunition. Not surprising when you consider that it took a lot of time to reload muzzle-loading weapons, which was a problem in itself. That is why the renowned commander urged the infantry to shoot accurately, and at the time of the attack, use the bayonet as efficiently as possible. Smoothbore guns of that time were never considered a priori rapid-fire, so a bayonet attack in battle was of great importance - a Russian grenadier could kill up to four opponents during a bayonet charge, while hundreds of bullets fired by ordinary infantrymen flew into milk. The bullets and guns themselves were not as effective as modern small arms, and their effective range was seriously limited.

For a long time, Russian gunsmiths simply did not create mass small arms without the possibility of using a bayonet with them. The bayonet was the infantry's faithful weapon in many wars, the Napoleonic wars were no exception. In battles with French troops, the bayonet more than once helped Russian soldiers gain the upper hand on the battlefield. The pre-revolutionary historian A.I. When his comrades died in battle, Leonty continued to fight alone. In battle, he broke his bayonet, but continued to fight off the enemy with the butt. As a result, he received 18 wounds and fell among the French killed by him. Despite his wounds, Korennoy survived and was taken prisoner. Struck by the courage of the warrior, Napoleon later ordered the release of the brave grenadier from captivity.

Subsequently, with the development of multiply charged and automatic weapons, the role of bayonet attacks decreased. In wars at the end of the 19th century, the number of killed and wounded with the help of cold weapons was extremely small. At the same time, a bayonet attack, in most cases, made it possible to turn the enemy into flight. In fact, not even the use of the bayonet itself began to play the main role, but only the threat of its use. Despite this, enough attention was paid to the techniques of bayonet attack and hand-to-hand combat in many armies of the world, the Red Army was no exception.

In the pre-war years in the Red Army, a sufficient amount of time was devoted to bayonet combat. Teaching servicemen the basics of such a battle was considered an important enough occupation. Bayonet fighting at that time constituted the main part of hand-to-hand combat, which was unequivocally stated in the specialized literature of that time ("Fencing and hand-to-hand combat", KT Bulochko, VK Dobrovolsky, 1940 edition). According to the Manual on preparation for hand-to-hand combat of the Red Army (NPRB-38, Voenizdat, 1938), the main task of bayonet combat was to train servicemen in the most expedient methods of offensive and defense, that is, “to be able at any moment and from different positions to quickly inflict jabs and blows on the enemy, beat off the enemy's weapon and immediately respond with an attack. To be able to apply this or that combat technique in a timely and tactically expedient manner. " Among other things, it was pointed out that bayonet fighting instills in the Red Army fighter the most valuable qualities and skills: quick reaction, agility, endurance and calmness, courage, determination, and so on.

G. Kalachev, one of the theorists of bayonet combat in the USSR, emphasized that a real bayonet attack requires courage from soldiers, the correct direction of strength and speed of reaction in the presence of a state of extreme nervous excitement and, possibly, significant physical fatigue. In view of this, it is required to develop the soldiers physically and maintain their physical development at the highest possible height. To transform the blow into a stronger one and gradually strengthen the muscles, including the legs, all trained fighters must practice and from the very beginning of the training, make attacks at short distances, jump into and jump out of dug trenches.

How important it is to train soldiers in the basics of hand-to-hand combat was shown by the battles with the Japanese near Lake Khasan and Khalkhin Gol and the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-40. As a result, the training of Soviet soldiers before the Great Patriotic War was carried out in a single complex, which combined bayonet fighting, throwing grenades and shooting. Later, during the war, especially in urban battles and in the trenches, new experience was obtained and generalized, which made it possible to strengthen the training of soldiers. Approximate tactics of storming enemy fortified areas were described by the Soviet command as follows: “From a distance of 40-50 meters, the attacking infantry must cease fire in order to reach the enemy trenches with a decisive throw. From a distance of 20-25 meters, it is necessary to use hand grenades thrown on the run. Then it is necessary to make a point-blank shot and ensure the defeat of the enemy with melee weapons. "

Such training was useful to the Red Army during the Great Patriotic War. Unlike Soviet soldiers, Wehrmacht soldiers in most cases tried to avoid hand-to-hand combat. The experience of the first months of the war showed that in bayonet attacks the Red Army most often prevailed over the enemy soldiers. However, very often such attacks were carried out in 1941 not because of a good life. Often a bayonet strike remained the only chance to break through from the still loosely closed ring of encirclement. The soldiers and commanders of the Red Army who were surrounded sometimes simply did not have ammunition left, which forced them to use a bayonet attack, trying to impose hand-to-hand combat on the enemy where the terrain allowed it.

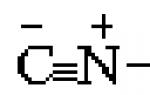

The Red Army entered the Great Patriotic War with the well-known tetrahedral needle bayonet, which was adopted by the Russian army back in 1870 and was originally adjacent to the Berdan rifles (the famous "Berdanka"), and later in 1891 a modification of the bayonet for the Mosin rifle appeared ( no less famous "three-line"). Even later, such a bayonet was used with the Mosin carbine of the 1944 model and the Simonov self-loading carbine of the 1945 model (SKS). In the literature, this bayonet is called the Russian bayonet. In close combat, the Russian bayonet was a formidable weapon. The tip of the bayonet was sharpened in the shape of a screwdriver. The injuries inflicted by the tetrahedral needle bayonet were heavier than those that could be inflicted with a bayonet knife. The depth of the wound was greater, and the entrance hole was smaller, for this reason, the wound was accompanied by severe internal bleeding. Therefore, such a bayonet was even condemned as an inhumane weapon, but it is hardly worth talking about the humanity of a bayonet in military conflicts that claimed tens of millions of lives. Among other things, the needle-like shape of the Russian bayonet reduced the chance of getting stuck in the enemy's body and increased the penetrating power, which was necessary to confidently defeat the enemy, even if he was wrapped up in winter uniforms from head to toe.

Russian tetrahedral needle bayonet for the Mosin rifle

Recalling their European campaigns, the Wehrmacht soldiers, in conversations with each other or in letters sent to Germany, voiced the idea that those who did not fight the Russians in hand-to-hand combat did not see a real war. Artillery shelling, bombing, skirmishes, tank attacks, marches through impassable mud, cold and hunger could not be compared with fierce and short hand-to-hand fights, in which it was extremely difficult to survive. They especially remembered the fierce hand-to-hand fighting and close combat in the ruins of Stalingrad, where the struggle was literally for individual houses and floors in these houses, and the path traveled in a day could be measured not only by meters, but also by the corpses of dead soldiers.

During the Great Patriotic War, the soldiers and officers of the Red Army were deservedly known as a formidable force in hand-to-hand combat. But the experience of the war itself demonstrated a significant decrease in the role of the bayonet during hand-to-hand combat. Practice has shown that Soviet soldiers used knives and sapper shovels more efficiently and successfully. The increasing distribution of automatic weapons in the infantry also played an important role. For example, submachine guns, which were massively used by Soviet soldiers during the war, did not receive bayonets (although they were supposed to), practice showed that short bursts at close range were much more effective.

After the end of the Great Patriotic War, the first Soviet serial machine gun - the famous AK, which was put into service in 1949, was equipped with a new model of melee weapons - a bayonet knife. The army understood perfectly well that the soldier would still need cold weapons, but multifunctional and compact. The bayonet-knife was intended to defeat enemy soldiers in close combat, for this he could either adjoin a machine gun, or, on the contrary, be used by a fighter as a regular knife. At the same time, the bayonet-knife received a blade shape, and in the future its functionality expanded mainly towards household use. Figuratively speaking, of the three roles "bayonet - knife - tool", preference was given to the latter two. Real bayonet attacks have forever remained on the pages of history textbooks, documentaries and feature films, but hand-to-hand combat has not gone anywhere. In the Russian army, as in the armies of most countries of the world, a sufficient share of attention is still paid to it in the training of military personnel.