Judging by historical sources, the most common type of armor in the 13th century was chain mail, consisting of iron rings connected to each other.

However, despite their widespread use, only a few chain mail dating back to before the 14th century have survived to this day. None of them were made in England.

Therefore, researchers rely mainly on images in manuscripts and sculptures.

To date, the secret of making chain mail has been largely lost, although descriptions of some procedures are known.

First, the iron wire was pulled through a board with holes of different diameters. The wire was then wound around steel rod and cut the resulting spiral lengthwise, forming separate rings.

The ends of the ring were flattened and a small hole was made in them. The rings were then woven so that each of them covered the other four. The ends of the ring were connected and secured with a small rivet.

To make one chain mail, several thousand rings were required.

The finished chain mail was sometimes cemented, heated in the thickness of burning coals.

In most cases, all chain mail rings were

riveted, sometimes rows alternated

riveted and welded rings.

| 1 |

Among the armor, chain mail occupied |

| 2 |

Bandaged riveted chain mail rings. |

| 3 |

Iron scale armor. |

| 4 |

Helmet with visor. |

| 5 |

Cylindrical helmet with nasal |

| 6 |

Helmet with chin plate. |

| 7 |

Round helmet with nasal plate. |

| 8 |

Conical helmet with lining. |

| 9 |

Quilted balaclava. |

| 10 |

Chain helmet. |

| Source | |

There were also large chain mail, which reached the knees in length and had long sleeves ending in mittens.

The collar of the large chain mail turned into a chain mail hood or balaclava.

To protect the throat and chin there was a valve, which before the battle was raised upward and secured with a ribbon.

Sometimes such a valve was missing, and the sides of the hood could overlap each other. Typically, the inner surface of the chain mail, which was in contact with the warrior’s skin, had a fabric lining.

In the lower part, the large chain mail had slits that made it easier for the warrior to walk and mount a horse.

A quilted cap was worn under the chain mail balaclava, which was held in place with ties under the chin.

| 11 |

Chain mail without surcoat and mittens. |

| 12 |

Surcoat worn over civilian clothing. |

| 13 |

Long shirt with Hungarian sleeves. |

| 14 |

Chainmail gauntlets. |

| 15 |

Chainmail stripe protecting the leg. |

| 16 |

Chain mail shawls tied to a belt. |

| Source : “English knight 1200-1300.” ( New Soldier № 10) | |

Around 1275, knights began to wear a chain mail balaclava separated from the chain mail, but the previous chain mail combined with a balaclava continued to be widely used until the end of the 13th century.

The chain mail weighed about 30 pounds (14 kg) depending on its length and the thickness of the rings. There were chain mail shirts with short and short sleeves.

Around the middle of the 13th century, Matthew of Paris depicted combat gloves separated from the sleeves of chain mail. However, such mittens were found

infrequently until the end of the century.

By that time, leather mittens with reinforcing linings made of iron or whalebone had appeared.

The pads could be located outside or inside the mitten.

Leg protection was provided by shossa - chain mail stockings. Shos had leather soles and were tied to a belt, like traditional stockings.

Linen underpants were worn under the highway pants.

Sometimes, instead of highways, the legs were protected with chain mail strips, covering only the front side of the leg, and held on by ribbons at the back.

Around 1225, quilted cuisses appeared, which were worn on the hips. Cuisses were also hung from the belt, like chausses.

In the middle of the century, the use of knee pads was noted for the first time, which were attached directly to chain mail chausses or to quilted cuisses.

Initially, knee pads were small size, but then sharply increased, covering the knees not only in front, but also on the sides.

Sometimes knee pads were made of hard leather. The knee pads were held in place by lacing or rivets.

Elbow pads were very rare.

The shins were covered with metal leggings worn over the shins.

| 1 |

Chain mail remains the main type |

| 2 | |

| 3 |

In the middle of the 12th century, a helmet appeared in |

| 4 |

A liner on a figured cap, worn under a large helmet. |

| 5 |

A cap with a shock absorber, worn under a large helmet. |

| 6 |

Internal helmet worn underneath |

| 7 |

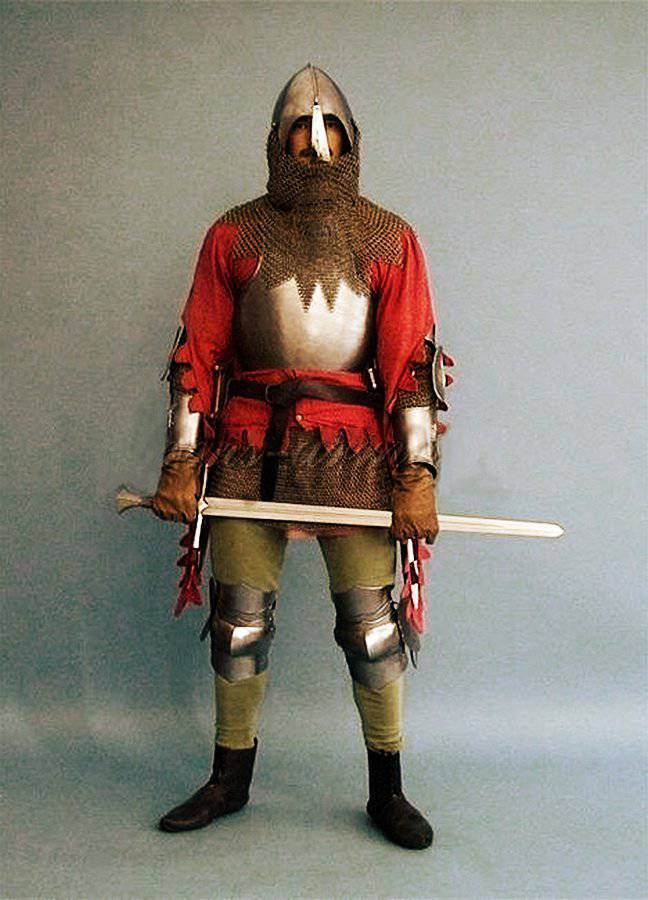

Surcoat with sleeves and fringe. |

| 8 |

Quilted cuisses that protect the hips. |

| 9 |

Highway knee brace. |

| 10 |

Knee pad on cuisses. |

| Source : “English knight 1200-1300.” (New Soldier #10) | |

A quilted aketon or gambeson was usually worn under the chain mail.

The aketon itself consisted of two layers of paper fabric, between which was placed a layer of wool, cotton wool and other similar materials.

Both layers, together with the interlining, were stitched with longitudinal or sometimes diagonal stitches. Later, aketons made of several layers of linen fabric appeared.

According to some descriptions, it is known that gambesons were worn over aketons. Gambesons could be made of silk and other expensive fabrics.

Sometimes they were worn on chain mail or plate armor.

Sometimes a long, loose shirt was worn over the chain mail. Shirt

was too mobile to be quilted.

Although chain mail, due to its flexibility, did not hinder the warrior’s movements, for the same reason, a missed blow could cause serious damage from bruise and contusion to a broken bone.

If the chain mail was pierced, fragments of links could get into the wound, which caused additional pain and threatened infection.

In some manuscripts of the 13th century you can find images of foot soldiers in leather armor, reinforced with metal plates.

In some illustrations in the Maciejowski Bible you can see warriors whose surcoats have a characteristic curve on their shoulders. It can be assumed that in this case a shell was worn under the surcoat.

There is another explanation.

Fawkes de Breaute's list (1224) mentions an "epaulier" made of black silk. Perhaps this meant a shoulder-shock absorber or a collar extending over the shoulders.

There were indeed special collars; they can be seen in several drawings depicting warriors with open vests or removed balaclavas. The outside of such a collar was lined with fabric, but the inside could be made of iron or whalebone. Individual collars were quilted.

It is unknown whether the collars were a separate part or were part of the aketon. It is also unknown how the collar was put on.

It could equally well have been in two pieces joined at the sides, or had a joint on one side and a clasp on the other.

| 1 |

By the end of the century, many knights |

| 2 |

Italian helmet. |

| 4 |

The helmet is a bowler hat. |

| 5 |

Balaclava with lacing at the back of the head. |

| 6 |

Elbow pad. |

| 7 | |

| 8 |

Lamellar shell. |

| 9 |

A combat gauntlet with whalebone scales. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | Waist belt with sword sheath. |

| 12 | Great sword. |

| 13 | Sword. |

| 14 | Sword. |

| 15 |

Garnache with hood. |

| Source : “English knight 1200-1300.” (New Soldier #10) | |

At the end of the century, gorgets, which came to England from France, began to be used to protect the neck.

A surcoat was a cape worn over armor.

The first surcoats appeared in the second quarter of the 12th century and spread everywhere by the beginning of the 13th century, although until the middle of the 13th century there were knights who did not have a surcoat. The main purpose of the surcoat is unknown.

Perhaps it protected the armor from water and prevented it from heating up in the sun.

You could wear your own coat of arms on a surcoat, although most often surcoats were one-color.

The lining of the surcoat usually contrasted with the color of the outer layer.

At the waist, the surcoat was usually intercepted with a cord or belt, which at the same time intercepted the chain mail, shifting part of its mass from the shoulders to the hips.

There were surcoats reinforced with metal plates.

In the middle of the 13th century, a new type of armor appeared - plate armor, which was worn over the head like a poncho, and then wrapped around the sides and fastened with ties or straps.

The front and sides of the shell were reinforced with a plate of iron or whalebone.

Scaly shells were rare. Scaled armor is sometimes found on book miniatures, but they are almost always worn by Saracens or

any other opponents of the Christian knights.

The scales were made of iron, copper alloy, whalebone or leather.

Each scale was attached to a cloth or leather shirt in such a way that the top row of scales overlapped the bottom.

There were several main types of helmets.

The conical helmet could be forged from a single piece of iron with or without the addition of reinforcing linings, or could consist of four segments connected by rivets, like the old German spangen helmet.

Such segmented helmets were also used in the middle of the 13th century, but even then they were considered obsolete.

By 1200, hemispherical and cylindrical helmets were found. All helmets had a nose plate and sometimes a visor.

At the end of the 12th century, the first primitive large helmets appeared. Originally, great helmets were shorter at the back than at the front, but already on the seal of Richard I there is an image of a great helmet equally deep both at the front and at the back.

Closed large helmets became increasingly popular throughout the 13th century. In front there was a narrow horizontal slit for the eyes, reinforced with metal plates.

The flat bottom of the helmet was attached to it with rivets. Although the bottom of the helmet should have been made conical or hemispherical for reasons of strength, this form of helmet took root and became widespread quite late.

| 1 |

This illustration is based on a miniature in a 13th-century Spanish manuscript. |

| 9 — 11 |

Bridle with mouthpiece. |

| Source : “English knight 1200-1300.” (New Soldier #10) | |

In the second half of the 13th century, the upper part of the walls of the helmet began to be made slightly conical, but the bottom remained flat. Only in 1275 did large helmets appear, in which the upper part was a full rather than a truncated cone.

By the end of the century, helmets with a hemispherical bottom appeared.

By 1300, helmets with a visor appeared.

In the middle of the 13th century, a bascinet helmet or cervelier appeared, having a spherical shape. The bascinet could be worn both over a chain mail balaclava and under it.

In the latter case, a shock absorber was put on the head.

All helmets had shock absorbers on the inside, although not a single example has survived to this day. The earliest surviving ones are shock absorbers

XIV century - represent two layers of canvas, between which horsehair, wool, hay or other similar substances are laid.

The shock absorber was either glued to the inside of the helmet, or laced through a series of holes, or secured with rivets.

The upper part of the shock absorber was adjustable in depth, allowing the helmet to be adjusted to the wearer's head so that the slots were at eye level.

For a large helmet, the lining did not go down to the level of the face, as there were ventilation holes there.

The helmet was held on the head by a chin strap.

At the end of the 12th century, a crest appeared on helmets. For example, such a helmet can be seen on the second seal of Richard I.

The crest was sometimes made from a thin sheet of iron, although wood and fabric were also used, especially on tournament helmets.

Sometimes there were voluminous combs made of whalebone, wood, fabric and leather.

“Oh, knights, arise, the hour of action has come!

Shields, steel helmets and you have armor.

Your dedicated sword is ready to fight for your faith.

Give me strength, oh God, for new glorious battles.

I, a beggar, will take rich spoils there.

I don’t need gold and I don’t need land,

But maybe I will be, singer, mentor, warrior,

Rewarded with heavenly bliss forever"

(Walter von der Vogelweide. Translation by V. Levick)

A sufficient number of articles on the topic of knightly weapons and, in particular, knightly armor have already been published on the VO website. However, this topic is so interesting that you can delve into it for a very long time. The reason for turning to her again is banal... weight. Weight of armor and weapons. Alas, I recently asked students again how much a knight’s sword weighs, and received the following set of numbers: 5, 10 and 15 kilograms. They considered chain mail weighing 16 kg to be very light, although not all of them did, and the weight of plate armor at just over 20 kilos was simply ridiculous.

Figures of a knight and a horse in full protective equipment. Traditionally, knights were imagined exactly like this - “chained in armor.” (Cleveland Museum of Art)

At VO, naturally, “things with weight” are much better due to regular publications on this topic. However, the opinion about the excessive weight of the “knightly costume” of the classical type has not yet been eradicated here. Therefore, it makes sense to return to this topic and consider it with specific examples.

Western European chain mail (hauberk) 1400 - 1460 Weight 10.47 kg. (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Let's start with the fact that British weapons historians created a very reasonable and clear classification of armor according to their specific characteristics and ultimately divided the entire Middle Ages, guided, naturally, by available sources, into three eras: “the era of chain mail”, “the era of mixed chain mail and plate protective weapons" and "the era of solid forged armor." All three eras together make up the period from 1066 to 1700. Accordingly, the first era has a framework of 1066 - 1250, the second - the era of chain mail-plate armor - 1250 - 1330. And then this: the early stage in the development of knightly plate armor (1330 - 1410), the “great period” in the history of knights in “white”, stands out armor" (1410 - 1500) and the era of decline of knightly armor (1500 - 1700).

Chain mail together with a helmet and aventail (aventail) XIII - XIV centuries. (Royal Arsenal, Leeds)

During the years of “wonderful Soviet education” we had never heard of such periodization. But in the school textbook “History of the Middle Ages” for VΙ grade for many years, with some rehashes, one could read the following:

“It was not easy for the peasants to defeat even one feudal lord. The mounted warrior - the knight - was armed with a heavy sword and a long spear. He could cover himself from head to toe with a large shield. The knight's body was protected by chain mail - a shirt woven from iron rings. Later, chain mail was replaced by armor - armor made of iron plates.

Classic knightly armor, which was most often discussed in textbooks for schools and universities. Before us is Italian armor of the 15th century, restored in the 19th century. Height 170.2 cm. Weight 26.10 kg. Helmet weight 2850 g (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Knights fought on strong, hardy horses, which were also protected by armor. The knight's weapons were very heavy: they weighed up to 50 kilograms. Therefore, the warrior was clumsy and clumsy. If a rider was thrown from his horse, he could not get up without help and was usually captured. To fight on horseback heavy armor, long training was needed, the feudal lords were preparing for military service since childhood. They constantly practiced fencing, horse riding, wrestling, swimming, and javelin throwing.

German armor 1535. Presumably from Brunswick. Weight 27.85 kg. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

A war horse and knightly weapons were very expensive: for all this a whole herd had to be given - 45 cows! The landowner for whom the peasants worked could perform knightly service. Therefore, military affairs became an occupation almost exclusively of feudal lords” (Agibalova, E.V. History of the Middle Ages: Textbook for the 6th grade / E.V. Agibalova, G.M. Donskoy, M.: Prosveshchenie, 1969. P.33; Golin, E.M. History of the Middle Ages: Tutorial for 6th grade evening (shift) school / E.M. Golin, V.L. Kuzmenko, M.Ya. Leuberg. M.: Education, 1965. P. 31-32.)

A knight in armor and a horse in horse armor. The work of master Kunz Lochner. Nuremberg, Germany 1510 - 1567 Dated 1548 Total weight rider's equipment including horse armor and saddle 41.73 kg. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Only in the 3rd edition of the textbook “History of the Middle Ages” for VΙ grade high school V.A. Vedyushkin, published in 2002, the description of knightly weapons became somewhat truly thoughtful and corresponded to the above-mentioned periodization used today by historians around the world: “At first, the knight was protected by a shield, helmet and chain mail. Then the most vulnerable parts of the body began to be hidden behind metal plates, and from the 15th century, chain mail was finally replaced by solid armor. Battle armor weighed up to 30 kg, so for battle the knights chose hardy horses, also protected by armor.”

Armor of Emperor Ferdinand I (1503-1564) Gunsmith Kunz Lochner. Germany, Nuremberg 1510 - 1567 Dated 1549. Height 170.2 cm. Weight 24 kg.

That is, in the first case, intentionally or out of ignorance, the armor was divided into eras in a simplified manner, while a weight of 50 kg was attributed to both the armor of the “era of chain mail” and the “era of all-metal armor” without dividing into the actual armor of the knight and the armor of his horse. That is, judging by the text, our children were offered information that “the warrior was clumsy and clumsy.” In fact, the first articles showing that this is actually not the case were publications by V.P. Gorelik in the magazines “Around the World” in 1975, but this information never made it into textbooks for Soviet schools at that time. The reason is clear. Using anything, using any examples, show the superiority of the military skills of Russian soldiers over the “dog knights”! Unfortunately, the inertia of thinking and the not-so-great significance of this information make it difficult to disseminate information that corresponds to scientific data.

Armor set from 1549, which belonged to Emperor Maximilian II. (Wallace Collection) As you can see, the option in the photo is tournament armor, as it features a grandguard. However, it could be removed and then the armor became combat. This achieved considerable savings.

Nevertheless, the provisions of the school textbook V.A. Vedyushkina are completely true. Moreover, information about the weight of armor, well, say, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (as well as from other museums, including our Hermitage in St. Petersburg, then Leningrad) was available for a very long time, but in the textbooks of Agibalov and Donskoy For some reason I didn’t get there in due time. However, it’s clear why. After all, we had the best education in the world. However, this is a special case, although quite indicative. It turned out that there were chain mail, then - again and again, and now armor. Meanwhile, the process of their appearance was more than lengthy. For example, only around 1350 was the appearance of the so-called “metal chest” with chains (from one to four) that went to a dagger, sword and shield, and sometimes a helmet was attached to the chain. Helmets at this time were not yet connected to protective plates on the chest, but under them they wore chain mail hoods that had a wide shoulder. Around 1360, armor began to have clasps; in 1370, the knights were almost completely dressed in iron armor, and chain mail fabric was used as a base. The first brigandines appeared - caftans, and lining made of metal plates. They were used as an independent type of protective clothing, and were worn together with chain mail, both in the West and in the East.

Knight's armor with a brigandine over chain mail and a bascinet helmet. Around 1400-1450 Italy. Weight 18.6 kg. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Since 1385, the thighs began to be covered with armor made of articulated strips of metal. In 1410, full-plate armor for all parts of the body had spread throughout Europe, but mail throat cover was still in use; in 1430, the first grooves appeared on the elbow and knee pads, and by 1450, armor made of forged steel sheets had reached its perfection. Beginning in 1475, the grooves on them became increasingly popular until fully fluted or so-called “Maximilian armor”, the authorship of which is attributed to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, became a measure of the skill of their manufacturer and the wealth of their owners. Subsequently, knightly armor became smooth again - their shape was influenced by fashion, but the skills achieved in the craftsmanship of their finishing continued to develop. Now it was not only people who fought in armor. The horses also received it, as a result the knight with the horse turned into something like a real statue made of polished metal that sparkled in the sun!

Another “Maximilian” armor from Nuremberg 1525 - 1530. It belonged to Duke Ulrich, the son of Henry of Württemberg (1487 - 1550). (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

Although... although fashionistas and innovators, “running ahead of the locomotive,” have always been there too. For example, it is known that in 1410 a certain English knight named John de Fiarles paid Burgundian gunsmiths 1,727 pounds sterling for armor, a sword and a dagger made for him, which he ordered to be decorated with pearls and... diamonds (!) - a luxury that was not only unheard of time, but even for him it is not at all characteristic.

Field armor of Sir John Scudamore (1541 or 1542-1623). Armourer Jacob Jacob Halder (Greenwich Workshop 1558-1608) Circa 1587, restored 1915. Weight 31.07 kg. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Each piece of plate armor received its own name. For example, plates for the thighs were called cuisses, knee pads - logs (poleyns), jambers (jambers) - for the legs and sabatons (sabatons) for the feet. Gorgets or bevors (gorgets, or bevors) protected the throat and neck, cutters (couters) - elbows, e(c)paulers, or pauldrones (espaudlers, or pauldrons) - shoulders, rerebraces (rerebraces) - forearm , vambraces - part of the arm down from the elbow, and gantelets - these are “plate gloves” - protected the hands. The full set of armor also included a helmet and, at least at first, a shield, which subsequently ceased to be used on the battlefield around the middle of the 15th century.

Armor of Henry Herbert (1534-1601), Second Earl of Pembroke. Made around 1585 - 1586. in the Greenwich armory (1511 - 1640). Weight 27.24 kg. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

As for the number of details in the “white armor”, in the armor of the mid-15th century there are total number could reach 200 units, and taking into account all the buckles and nails, along with hooks and various screws, even up to 1000. The weight of the armor was 20 - 24 kg, and it was distributed evenly over the knight’s body, unlike chain mail, which pressed on the person on shoulders. So “no crane was required to put such a rider in his saddle. And knocked off his horse to the ground, he did not at all look like a helpless beetle.” But the knight of those years was not a mountain of meat and muscles, and he by no means relied solely on brute strength and bestial ferocity. And if we pay attention to how knights are described in medieval works, we will see that very often they had a fragile (!) and graceful physique, and at the same time had flexibility, developed muscles, and were strong and very agile, even when dressed in armor, with well-developed muscle response.

Tournament armor made by Anton Peffenhauser around 1580 (Germany, Augsburg, 1525-1603) Height 174.6 cm); shoulder width 45.72 cm; weight 36.8 kg. It should be noted that tournament armor was usually always heavier than combat armor. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

IN last years In the 15th century, knightly weapons became the subject of special concern for European sovereigns, and, in particular, Emperor Maximilian I (1493 - 1519), who is credited with creating knight's armor with grooves along their entire surface, eventually called “Maximilian”. It was used without any special changes in the 16th century, when new improvements were required due to the ongoing development of small arms.

Now just a little about swords, because if you write about them in detail, then they deserve a separate topic. J. Clements, a well-known British expert on edged weapons of the Middle Ages, believes that it was the advent of multi-layer combined armor (for example, on the effigy of John de Creque we see as many as four layers of protective clothing) that led to the appearance of a “sword in one and a half hands.” Well, the blades of such swords ranged from 101 to 121 cm, and weight from 1.2 to 1.5 kg. Moreover, blades are known for chopping and piercing blows, as well as purely for stabbing. He notes that horsemen used such swords until 1500, and they were especially popular in Italy and Germany, where they were called Reitschwert (equestrian) or knight's sword. In the 16th century, swords appeared with wavy and even jagged sawtooth blades. Moreover, their length itself could reach human height with a weight of 1.4 to 2 kg. Moreover, such swords appeared in England only around 1480. Average weight sword in the X and XV centuries. was 1.3 kg; and in the sixteenth century. - 900 g. Bastard swords “one and a half hands” weighed about 1.5 - 1.8 kg, and the weight of two-handed swords was rarely more than 3 kg. The latter reached their peak between 1500 and 1600, but were always infantry weapons.

Three-quarter cuirassier armor, ca. 1610-1630 Milan or Brescia, Lombardy. Weight 39.24 kg. Obviously, since they have no armor below the knees, the extra weight comes from thickening the armor.

But shortened three-quarter armor for cuirassiers and pistoleers, even in its shortened form, often weighed more than those that offered protection only from edged weapons and they were very heavy to wear. Cuirassier armor has been preserved, the weight of which was about 42 kg, i.e. even more than classic knightly armor, although they covered a much smaller surface of the body of the person for whom they were intended! But this, it should be emphasized, is not knightly armor, that’s the point!

Horse armor, possibly made for Count Antonio IV Colalto (1548-1620), circa 1580-1590. Place of manufacture: probably Brescia. Weight with saddle 42.2 kg. (Metropolitan Museum, New York) By the way, a horse in full armor under an armored rider could even swim. The horse armor weighed 20-40 kg - a few percent of the own weight of a huge and strong knight's horse.

In this article, in the most general outline The process of development of armor in Western Europe in the Middle Ages (VII - late XV centuries) and at the very beginning of the early modern period (early XVI century) is considered. Material supplied big amount illustrations for a better understanding of the topic. Most of text translated from English.

Mid-VIIth - IX centuries. Viking in a Vendel helmet. They were used mainly in Northern Europe by the Normans, Germans, etc., although they were often found in other parts of Europe. Very often has a half mask covering the upper part of the face. Later evolved into the Norman helmet. Armor: short chain mail without a chain mail hood, worn over a shirt. The shield is round, flat, medium in size, with a large umbon - a metal convex hemispherical plate in the center, typical of Northern Europe of this period. On shields, a gyuzh is used - a belt for wearing the shield while marching on the neck or shoulder. Naturally, horned helmets did not exist at that time.

X - beginning of XIII centuries. Knight in a Norman helmet with rondache. An open Norman helmet of a conical or ovoid shape. Usually,

A nasal plate is attached in front - a metal nasal plate. It was widespread throughout Europe, both in the western and eastern parts. Armor: long chain mail to the knees, with sleeves of full or partial (to the elbows) length, with a coif - a chain mail hood, separate or integral with the chain mail. In the latter case, the chain mail was called “hauberk”. The front and back of the chain mail have slits at the hem for more comfortable movement (and it’s also more comfortable to sit in the saddle). From the end of the 9th - beginning of the 10th centuries. under the chain mail, knights begin to wear a gambeson - a long under-armor garment stuffed with wool or tow to such a state as to absorb blows to the chain mail. In addition, arrows were perfectly stuck in gambesons. It was often used as a separate armor by poorer infantrymen compared to knights, especially archers.

Bayeux Tapestry. Created in the 1070s. It is clearly visible that the Norman archers (on the left) have no armor at all

Chain mail stockings were often worn to protect the legs. From the 10th century a rondache appears - a large Western European shield of knights of the early Middle Ages, and often infantrymen - for example, Anglo-Saxon huskerls. It could have a different shape, most often round or oval, curved and with a umbon. For knights, the rondache almost always has a pointed shape at the bottom - the knights used it to cover left leg. Produced in various versions in Europe in the 10th-13th centuries.

Attack of knights in Norman helmets. This is exactly what the crusaders looked like when they captured Jerusalem in 1099

XII - early XIII centuries. A knight in a one-piece Norman helmet wearing a surcoat. The nosepiece is no longer attached, but is forged together with the helmet. Over the chain mail they began to wear a surcoat - a long and spacious cape of different styles: with and without sleeves of various lengths, plain or with a pattern. The fashion began with the first Crusade, when the knights saw similar cloaks among the Arabs. Like chain mail, it had slits at the hem at the front and back. Functions of the cloak: protecting the chain mail from overheating in the sun, protecting it from rain and dirt. Rich knights, in order to improve protection, could wear double chain mail, and in addition to the nosepiece, attach a half mask that covered the upper part of the face.

Archer with a long bow. XI-XIV centuries

End of XII - XIII centuries. Knight in a closed sweatshirt. Early pothelmas were without facial protection and could have a nose cap. Gradually the protection increased until the helmet completely covered the face. Late Pothelm is the first helmet in Europe with a visor that completely covers the face. By the middle of the 13th century. evolved into topfhelm - a potted or large helmet. The armor does not change significantly: still the same long chain mail with a hood. Muffers appear - chain mail mittens woven to the houberk. But they did not become widespread; leather gloves were popular among knights. The surcoat somewhat increases in volume, in its largest version becoming a tabard - a garment worn over armor, sleeveless, on which the owner’s coat of arms was depicted.

King Edward I Longshanks of England (1239-1307) wearing an open sweatshirt and tabard

First half of the 13th century. Knight in topfhelm with targe. Topfhelm is a knight's helmet that appeared at the end of the 12th - beginning of the 13th century. Used exclusively by knights. The shape can be cylindrical, barrel-shaped or in the shape of a truncated cone, it completely protects the head. The tophelm was worn over a chainmail hood, under which, in turn, a felt liner was worn to cushion blows to the head. Armor: long chain mail, sometimes double, with a hood. In the 13th century appears as a mass phenomenon, chainmail-brigantine armor, providing more strong defense than just chain mail. Brigantine is armor made of metal plates riveted on a cloth or quilted linen base. Early chain mail-brigantine armor consisted of breastplates or vests worn over chain mail. The shields of the knights, due to the improvement by the middle of the 13th century. protective qualities of armor and the appearance of fully closed helmets, significantly decrease in size, turning into a targe. Tarje is a type of shield in the shape of a wedge, without a umbon, actually a version of the teardrop-shaped rondache cut off at the top. Now knights no longer hide their faces behind shields.

Brigantine

Second half of the XIII - beginning of the XIV centuries. Knight in topfhelm in surcoat with aylettes. Specific feature Topfhelms have very poor visibility, so they were used, as a rule, only in spear clashes. Topfhelm is poorly suited for hand-to-hand combat due to its disgusting visibility. Therefore, the knights, if it came to hand-to-hand combat, threw him down. And so that the expensive helmet would not be lost during battle, it was attached to the back of the neck with a special chain or belt. After which the knight remained in a chainmail hood with a felt liner underneath, which was weak protection against the powerful blows of a heavy medieval sword. Therefore, very soon the knights began to wear a spherical helmet under the tophelm - a cervelier or hirnhaube, which is a small hemispherical helmet that fits tightly to the head, similar to a helmet. The cervelier does not have any elements of facial protection; only very rare cerveliers have nose guards. In this case, in order for the tophelm to sit more tightly on the head and not move to the sides, a felt roller was placed under it over the cervelier.

Cervelier. XIV century

The tophelm was no longer attached to the head and rested on the shoulders. Naturally, the poor knights managed without a cervelier. Ayletts are rectangular shoulder shields, similar to shoulder straps, covered with heraldic symbols. Used in Western Europe in the 13th - early 14th centuries. as primitive shoulder pads. There is a hypothesis that epaulettes originated from the Ayletts.

From the end of the XIII - beginning of the XIV centuries. Tournament helmet decorations became widespread - various heraldic figures (cleinodes), which were made of leather or wood and attached to the helmet. Various types of horns became widespread among the Germans. Ultimately, topfhelms fell completely out of use during the war, leaving pure tournament helmets for a spear collision.

First half of the 14th - beginning of the 15th centuries. Knight in bascinet with aventile. In the first half of the 14th century. The topfhelm is replaced by a bascinet - a spheroconic helmet with a pointed top, to which is woven an aventail - a chainmail cape that frames the helmet along the lower edge and covers the neck, shoulders, back of the head and sides of the head. The bascinet was worn not only by knights, but also by infantrymen. There are a huge number of varieties of bascinets, both in the shape of the helmet and in the type of fastening of the visor of various types, with and without a nosepiece. The simplest, and therefore most common, visors for bascinets were relatively flat clapvisors - in fact, a face mask. At the same time, a variety of bascinets with a visor, the Hundsgugel, appeared - the ugliest helmet in Europe, nevertheless very common. Obviously, security at that time was more important than appearance.

Bascinet with Hundsgugel visor. End of the 14th century

Later, from the beginning of the 15th century, bascinets began to be equipped with plate neck protection instead of chain mail aventail. Armor at this time also developed along the path of increasing protection: chain mail with brigantine reinforcement was still used, but with larger plates that could withstand blows better. Individual elements of plate armor began to appear: first plastrons or placards that covered the stomach, and breastplates, and then plate cuirasses. Although, due to their high cost, plate cuirasses were used at the beginning of the 15th century. were available to few knights. Also appearing in large quantities: bracers - part of the armor that protects the arms from the elbow to the hand, as well as developed elbow pads, greaves and knee pads. In the second half of the 14th century. The gambeson is replaced by the aketon - a quilted underarmor jacket with sleeves, similar to a gambeson, only not so thick and long. It was made from several layers of fabric, quilted with vertical or rhombic seams. Additionally, I no longer stuffed myself with anything. The sleeves were made separately and laced to the shoulders of the aketon. With the development of plate armor, which did not require such thick underarmor as chain mail, in the first half of the 15th century. The aketone gradually replaced the gambeson among the knights, although it remained popular among the infantry until the end of the 15th century, primarily because of its cheapness. In addition, richer knights could use a doublet or purpuen - essentially the same aketon, but with enhanced protection from chain mail inserts.

This period, the end of the 14th - beginning of the 15th centuries, is characterized by a huge variety of combinations of armor: chain mail, chain mail-brigantine, composite of a chain mail or brigantine base with plate breastplates, backrests or cuirasses, and even splint-brigantine armor, not to mention all kinds of bracers , elbow pads, knee pads and greaves, as well as closed and open helmets with a wide variety of visors. Small shields (tarzhe) are still used by knights.

Looting the city. France. Miniature from the early 15th century.

By the middle of the 14th century, following the new fashion for shortening outer clothing that had spread throughout Western Europe, the surcoat was also greatly shortened and turned into a zhupon or tabar, which performed the same function. The bascinet gradually developed into the grand bascinet - a closed helmet, round, with neck protection and a hemispherical visor with numerous holes. It fell out of use at the end of the 15th century.

First half and end of the 15th century. Knight in a salad. All further development of armor follows the path of increasing protection. It was the 15th century. can be called the age of plate armor, when they became somewhat more accessible and, as a result, appeared en masse among knights and, to a lesser extent, among infantry.

Crossbowman with paveza. Mid-second half of the 15th century.

As blacksmithing developed, the design of plate armor became more and more improved, and the armor itself changed according to armor fashion, but Western European plate armor always had the best protective qualities. By the middle of the 15th century. the arms and legs of most knights were already completely protected by plate armor, the torso by a cuirass with a plate skirt attached to the lower edge of the cuirass. Also, plate gloves are appearing en masse instead of leather ones. Aventail is being replaced by gorje - plate protection of the neck and upper chest. It could be combined with both a helmet and a cuirass.

In the second half of the 15th century. arme appears - new type knight's helmet XV-XVI centuries, with double visor and neck protection. In the design of the helmet, the spherical dome has a rigid back part and movable protection of the face and neck on the front and sides, over which a visor attached to the dome is lowered. Thanks to this design, the armor provides excellent protection both in a spear collision and in hand-to-hand combat. Arme is the highest level of evolution of helmets in Europe.

Arme. Mid-16th century

But it was very expensive and therefore available only to rich knights. Most of the knights from the second half of the 15th century. wore all kinds of salads - a type of helmet that is elongated and covers the back of the neck. Salads were widely used, along with chapelles - the simplest helmets - in the infantry.

Infantryman in chapelle and cuirass. First half of the 15th century

For knights, deep salads were specially forged with full protection of the face (the fields in front and on the sides were forged vertical and actually became part of the dome) and neck, for which the helmet was supplemented with a bouvier - protection for the collarbones, neck and lower part of the face.

Knight in chapelle and bouvigère. Middle - second half of the 15th century.

In the 15th century There is a gradual abandonment of shields as such (due to the massive appearance of plate armor). Shields in the 15th century. turned into bucklers - small round fist shields, always made of steel and with a umbon. They appeared as a replacement for knightly targes for foot combat, where they were used to parry blows and strike the enemy’s face with the umbo or edge.

Buckler. Diameter 39.5 cm. Beginning of the 16th century.

The end of the XV - XVI centuries. Knight in full plate armor. XVI century Historians no longer date it back to the Middle Ages, but to the early modern era. Therefore, full plate armor is more a phenomenon of the New Age than of the Middle Ages, although it appeared in the first half of the 15th century. in Milan, famous as a production center best armor in Europe. In addition, full plate armor was always very expensive, and therefore was available only to the wealthiest part of the knighthood. Full plate armor, covering the entire body with steel plates and the head with a closed helmet, is the culmination of the development of European armor. Poldrones appear - plate shoulder pads that provide protection for the shoulder, upper arm, and shoulder blades with steel plates due to their rather large size. Also, to enhance protection, they began to attach tassets - hip pads - to the plate skirt.

During the same period, the bard appeared - plate horse armor. They consisted of the following elements: chanfrien - protection of the muzzle, critnet - protection of the neck, peytral - protection of the chest, crupper - protection of the croup and flanshard - protection of the sides.

Full armor for knight and horse. Nuremberg. Weight (total) of the rider’s armor is 26.39 kg. The weight (total) of the horse's armor is 28.47 kg. 1532-1536

At the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th centuries. two mutually opposite processes take place: if the armor of the cavalry is increasingly strengthened, then the infantry, on the contrary, is increasingly exposed. During this period, the famous Landsknechts appeared - German mercenaries who served during the reign of Maximilian I (1486-1519) and his grandson Charles V (1519-1556), who retained for themselves, at best, only a cuirass with tassets.

Landsknecht. The end of the 15th - first half of the 16th centuries.

Landsknechts. Engraving from the early 16th century.

Knightly armor and weapons of the Middle Ages changed almost at the same speed as modern fashion. And knightly armor from the mid-15th century. did not even remotely resemble what warriors used to protect themselves in the 12th or 13th centuries. The evolution became especially noticeable in the late Middle Ages, when almost every year brought changes in the appearance of defensive and offensive weapons. In this review, we will talk about what kind of armor the English and French knights wore in the era when, under the leadership of the legendary Joan of Arc, the French defeated the English troops near Orleans, and there was a turning point in the Hundred Years' War.

By the end of the XIV - beginning of the XV century. The appearance of full plate armor finally took shape. In the 20-30s. XV century The best armor was considered to be made by Italian and, above all, Milanese gunsmiths, famous for the extraordinary skill of their work. Along with the Italian ones, gunsmiths from the south of Germany and the Netherlands were also popular.

Armor

Underarmor. A thick quilted jacket was mandatory to be worn under the armor. It was sewn from leather or strong, coarse material on horsehair, cotton wool or tow. In the XIII-XIV centuries. this fabric armor was called “aketon”, in the 15th century. the term “doublet” was assigned to it. The protective properties of any armor largely depended on the thickness of the padding and the quality of the quilting of the doublet. After all, a strong blow could, without breaking through the armor, seriously injure the owner. The doublet was cut according to the style that was fashionable in the 15th century. a short, fitted jacket, usually with a front fastening and a stand-up collar. The long sleeves of the doublet could not be sewn, but laced to the armholes. The thickest padding covered the most vulnerabilities body: neck, chest, stomach. On the elbows and under the arms the padding was very thin or completely absent, so as not to restrict the warrior’s movements.

A quilted balaclava was also worn on the head under the helmet. One liner, as a rule, was mounted inside the helmet, the second, thinner and smaller, was worn directly on the head like a cap. Such powerful shock-absorbing pads caused extremely big size helmet, which significantly exceeded the size of the knight's head.

Quilted linings were also required to be worn under the leg armor.

By the first third of the 15th century. knights used four types of helmets: bassinet, arme, salade and helmets with brims (chapelle de fer).

Basinet was very popular already in the 14th century. This is a helmet with a hemispherical or conical head equipped with a visor. Basinets of the late XIV - early XV centuries. had a back plate that went down onto the warrior’s back, as well as a collar, which reliably protected the warrior’s head and neck. Basinettes with an elongated backplate and neck plate were called “large bassinettes” and became quite widespread. Large Basinettes were always equipped with a visor. At the end of the 14th century. The conical visor, which, because of its shape, was called “hundgugel” (dog head) in German, was extremely popular. Thanks to this shape, even powerful blows from the spear slipped off without causing harm. To make breathing easier and provide better review The visors were equipped with a lower slot at the level of the mouth and numerous round holes. These holes could only be located on the right half of the visor, which was determined by the conditions of equestrian combat with spears, in which the left half of the warrior’s helmet was primarily affected.

Fig.2 Helmet with open and closed visor

At the beginning of the 15th century. Another type of helmet appeared, which later became the very popular “Arme” helmet. The main difference between arme and basinet, in the 30s of the 15th century, was the presence of two cheek plates equipped with hinges, closing in front of the chin and locking with a hook or a belt with a buckle.

Another type of helmet originates from the bassinet, namely the so-called “salad” (in German “shaler”). The term “salade” was first used in 1407. By the time of the siege of Orleans, it began to be equipped with a movable visor attached to two hinges.

At the beginning of the 15th century. Helmets with brims were very popular. These helmets, made in the shape of an ordinary hat (hence the French name “chapel-de-fer”, literally “hat made of iron”), did not impede breathing and provided full visibility. At the same time, the overhanging fields protected the face from lateral impacts. This helmet was most widespread in the infantry, but knights and even crowned heads did not neglect it. Not long ago, during excavations in the Louvre, a luxurious chapel de fer of Charles VI, decorated with gold, was found. The heavy cavalry in the front ranks of the battle formation, which took the first, most terrible spear blow, wore closed helmets, while the fighters in the rear ranks often used helmets with brims.

Helmets of all types under consideration were decorated in accordance with fashion, the desire of the owner and the characteristics of a particular region. Thus, the French knights were characterized by plumes attached to tubes installed in the upper part of the helmet. English knights preferred to wear embroidered “burelets” (stuffed bolsters) on their helmets, and in most cases they did without them. Helmets could also be gilded or painted with tempera paints.

Note that English knights preferred basinettes and only occasionally wore chapelle-de-ferres. The French used all of these types of helmets.

Cuirass. The main element of armor that protected the body was the cuirass. Cuirasses of the 20-30s. XV century were monolithic and composite. Monolithic ones consisted of only two parts: a breastplate and a backrest. In composite ones, the breastplate and backrest were assembled from two parts, upper and lower. The top and bottom of classic Italian cuirasses were connected to each other by belts with buckles. Cuirasses produced for sale to other countries were made with sliding rivets that replaced belts. The breastplate and backrest of the first version were connected on the left side with a loop and fastened on the right side with a buckle. The parts of the cuirass of the second version were connected on the sides by means of belts with buckles. Monolithic cuirasses were more typical of English chivalry, while composite ones were more typical of French chivalry.

Lamellar hems covered the body from the waist to the base of the hips and had smooth outlines. They were assembled from horizontal steel strips stacked on top of each other from bottom to top. They were connected along the edges with rivets; an additional leather strip, riveted from the inside, was usually passed through the center. The number of steel hem strips varied from four to seven or even eight. By the second half of the 1420s. Plates began to be hung on belts from the bottom of the hem, covering the base of the thigh. These plates were called "tassets".

Brigantine. In addition to cuirasses, knights of both warring sides continued to use brigantines - armor consisting of small plates attached to the inside of fabric jackets with rivets. The fabric base was made of velvet with a lining of linen, hemp or thin leather. The most common brigantine tire colors were red and blue.

Since the 30s. XV century brigantines could be reinforced with all-metal elements, namely the lower part of the composite cuirass and a plate hem.

For the convenience of using spears in equestrian combat from the end of the 14th century. the right side of the chest part of the brigantine or cuirass began to be equipped with a support hook. During a horse fight, the shaft of a spear was placed on it.

Hand protection. The warrior’s hands were protected with special steel pads: bracers, elbow pads, shoulder guards, and shoulder pads. The bracers consisted of two wings, connected by a loop and straps with buckles. Elbow pads are strongly convex plates of a hemispherical, conical or dome shape. The outer part of the elbow pads, as a rule, was equipped with a side shield shaped like a shell. The shoulder shield had the shape of a monolithic pipe. The shoulder pad protected the shoulder joint. The armpit could be covered with an additional hanging plate of one shape or another.

An interesting type of covering the shoulder joint were brigantine shoulder pads. They were made in the manner of ordinary brigantine armor with steel plates under the fabric. Such pauldrons were either fastened (laced) to the armor, like a plate pauldron, or cut out with a brigantine.

The hands were covered with plate gloves or mittens. They were made from strips of iron and plates of various shapes and fastened with hinges. The plates that protected the fingers were riveted to narrow leather strips, which, in turn, were sewn to the fingers of ordinary gloves. In the 1420s In Italy, gauntlets made of wide strips of steel with a hinge joint were invented. At the time of the Siege of Orleans, this progressive innovation was just beginning to gain popularity in Western Europe and was rarely used by anyone except the Italians.

Leg protection. The armor that covered the legs was traditionally ahead of the development of wrist armor. The leg guard was connected to the knee pad through adapter plates on hinges. The knee pad, like the elbow pad, was complemented on the outside with a shell-shaped side shield. The lower part of the knee pad was equipped with several transition plates, the last of which was in the fashion of the 15th century. had a considerable length, up to about a third of the shin (sometimes up to the middle of the shin). In the 1430s. or a little earlier, the upper part of the legguard began to be supplemented with one transition plate, for a better fit of the leg, as well as to enhance the protection of the base of the thigh. The back of the thigh was covered with several vertical stripes on loops and buckles. A double-leaf plate greave was worn under the lower transition plates of the knee pad. The greave accurately repeated the features of the anatomical structure of the lower leg, which met the requirements of convenience and practicality. The foot was placed in the arched cutout of the front flap of the greave. This cutout was rolled around the perimeter to increase the rigidity of the greave.

The foot was protected by a plate shoe “sabaton” or “soleret”. Like the plate gauntlet, the sabaton was made up of transverse strips on hinges. Its toe had a pointed shape in the style of an ordinary leather “pulen” shoe.

Leg and wrist armor were decorated with plates made of non-ferrous metal, often chased or engraved with various geometric patterns.

The weight of the knightly armor we are considering from the first third of the 15th century. together with quilted and chain mail elements, it weighed 20-25 kg, but heavier specimens could also be found. In most cases, it depended on the physical characteristics of its owner. The thickness of the plates was, as a rule, from 1 to 3 mm. The protective parts covering the warrior’s torso, head and joints had the greatest thickness. The surface of plate armor was additionally saturated with carbon and subjected to heat treatment (hardening), due to which the plates acquired increased strength properties.

Initially, greaves with sabatons were put on, then a quilted doublet was put on the warrior’s body, to which greaves connected to knee pads were laced. Then the wrist armor was put on, laced to the upper part of the doublet sleeve. Subsequently, a cuirass with a plate hem or a brigantine was put on the warrior’s body. After the shoulder pads were secured, a quilted balaclava with a helmet was placed on the warrior’s head. Plate gloves were worn immediately before battle. Dressing a knight in full armor required the help of one or two experienced squires. The process of putting on and adjusting equipment took from 10 to 30 minutes.

During the time period under review, the chivalry of both warring sides still used the shield. The shield was made from one or several boards. It had a different shape (triangular, trapezoidal, rectangular), one or more parallel edges passing through the central part of the shield, and a cutout for a spear located on the right side. The surface of the shield was covered with leather or fabric, after which it was primed and covered with tempera painting. The images on the shields were the coats of arms of the owners, allegorical drawings, “floral” ornaments, and the mottos of the owners or units. A system of belts and a padded shock-absorbing cushion were attached to the inside of the shield.

Weapon

Edged weapons consisted of swords, cutlasses (falchions), daggers, combat knives, stilettos, axes, axes, war hammers, pickers, maces, swords and spears.

Clad in perfect armor and armed with high-quality bladed weapons, the English and French knights fought on the battlefields of the Hundred Years' War with varying degrees of success for a long time after the siege of Orleans.

Falchion (falchion) It was a piercing-cutting-chopping weapon, consisting of a massive curved or straight asymmetrical single-edged blade, often greatly expanding towards the tip, a cross-shaped guard, a handle and a pommel. This weapon, which had a massive blade, made it possible to penetrate chain mail protection. In the case where the blow landed on a warrior’s helmet, the enemy could be temporarily stunned. Due to the relatively long length blade, the use of falchions was especially effective in foot combat.

Battle ax It was a metal piece of iron (this part corresponds to the tip of a pole weapon), equipped with a wedge (a damaging structural element) and mounted on the handle. Very often, the piece of iron was equipped with a spike-shaped, hook-shaped or pronounced hammer-shaped protrusion on the side of the butt and a lance-shaped or spear-shaped feather directed upward. Two-handed ax already belonged to polearms and was very popular weapon foot combat, as it had monstrous penetrating ability and a significant bruising effect.

War Hammer, belonging to the category of pole weapons, initially with only impact-crushing action, was a tip in the form of a metal striker of a cylindrical or coil shape, mounted on a wooden shaft. Quite often in the 15th century. such weapons were equipped with a spear-shaped or lance-shaped tip. The shaft was almost always bound with metal strips, protecting it from chopping blows and splitting.

Pernach was a weapon of shock-crushing action, consisting of a pommel and a handle. The pommel is a complex of impact striking elements in the form of plates of rectangular, triangular, trapezoidal and other shapes, assembled in an amount of 6 to 8 pieces around the circumference and fixed on a common tubular base.

Mace, just like the pernach, being a weapon of shock-crushing action, it consisted of a pommel and a handle. The pommel was made in the form of a metal ball, often equipped with edges or spikes.

Battle scourge was a weapon of shock-crushing action. It was a massive impact load (weight), connected to the handle by means of a flexible suspension (rope, leather belt or chain).

A spear It was the knight's main polearm piercing weapon. This weapon consisted of a steel tip and a wooden shaft equipped with a safety shield. The tip consisted of a faceted feather and a sleeve, through which the tip was attached to the shaft. The shaft was made of hardwood (ash, elm, birch) and had an elongated spindle-shaped shape. To make it easier to control the spear during battle, the shaft was equipped with a protective shield or a special cutout. To improve balance, lead was poured into the back of the shaft.

Sword consisted of a straight double-edged blade with a pronounced tip, a guard in the form of a cross, a handle and a pommel. Particularly popular were swords with a blade that smoothly tapered to the tip, had a diamond-shaped cross-section, a significant blade thickness and increased rigidity. With such a weapon it was possible to deliver effective piercing blows, capable of hitting the vulnerable spots of plate armor, the application of slashing blows to which did not bring the desired result.

Dagger, in the period under review, consisted of a narrow piercing-cutting double-edged blade, a guard of various shapes, a handle and in rare cases pommel. The dagger was an almost unchanged attribute of secular and military costume. Its presence on the owner’s belt allowed him to get rid of annoying attacks on his wallet in urban conditions, and in battle it made it possible to hit the enemy in the joints and crevices of his armor.

Combat knife in its design and appearance it was not much different from a dagger and performed the same functions as the latter. The main difference was that the knife had a massive elongated triangular single-edged blade.

Stylet, being only a piercing weapon, consisted of a faceted blade with only an edge, a disc-shaped guard, the same pommel and a cylindrical or barrel-shaped handle. This weapon was not yet widely used during this period.

Ax consisted of structural elements similar structural elements battle axe. The main difference between these related groups of bladed weapons was the presence of a wedge in the ax, the width of which was greater than its length and increased in both directions relative to the vertical plane of the weapon when held with a piece of iron or the tip up. Like a battle axe, this weapon, being a weapon of wealthy warriors, could be richly decorated in the Gothic style.

It should be especially noted that as battle axes, and axes, belonging to the category of polearms, were especially popular in France throughout the 15th century.

Klevets It was a weapon of shock-crushing, piercing action and existed in several versions. One option was a weapon equipped with a handle and did not differ in significant size; the other, due to its size and long handle, can be classified as a pole weapon. A common design feature of these varieties was the presence of a striking structural element in the form of a metal wedge equipped with a tip and a hammer-like thickening of the butt.

On the left is a reconstruction of the weapons of a French knight in the 20-30s. XV century. The knight's armor shows strong influence Italian gunsmiths. On the right is a reconstruction of weapons English knight in 20-30 years. XV century. Despite the strong Italian influence, the armor has pronounced national features. The author of both reconstructions is K. Zhukov. Artist: S. Letin

Magazine “Empire of History” No. 2 (2) for 2002

Knights of Western Europe

Klim Zhukov and Dmitry Korovkin

pp. 72-81

Since the beginning of human society, warriors have protected their bodies from attacks from enemies. Initially, armor protected only the most vulnerable parts of the body, but by the 14th century, knightly armor completely covered the entire body.

In the 11th century, a warrior's armor consisted of a strong base to which square or round iron plates were attached, overlapping each other. This armor protected the body and partially the arms and legs. Already in the 12th century, changes were made to the design of armor, which gave rise to the so-called haubert.

Such armor consisted of iron scales located on top of each other, of iron rings connected to each other, or plaques sewn end to end. Haubert had already covered his head with a special hood, and his arms and legs were almost completely covered. To make it possible to freely mount a horse in the haubert, special cuts were made on the sides and sometimes in the back. The haubert was worn over a long quilted shirt.

In the 12th century, during crusades When the influence of the East spread to Central Europe, chain mail appeared.

It was made from intertwined welded or riveted iron rings. The chain mail covered the head with a hood, and to protect the legs, the knights wore chain mail pants in the form of stockings along with the armor, which also protected the foot.

12th century chainmail

Since the 12th century, chain mail trousers began to be worn together with the haubert. Chain mail became integral to the knight.

During the Crusades, when they had to fight under the hot sun of the east, chain mail became very hot. To reduce heat, white sleeveless capes with slits on the sides were worn on top of the chain mail.

12th century helmet

If earlier the haubert was long, then in the 13th century it shortened and began to reach only to the middle of the thighs, which made the knights more agile, and they began to cover their shoulders and knees with iron discs. If the legs were not covered with chain mail, then they were protected by a strip of strong boiled leather, which was fastened at the back.

Knight of the 12th century

The first plate armor appeared in the 13th century.

They were iron plates that were secured with belts over the haubert and chain mail pants.

In the 14th century, iron greaves were used to protect the front surfaces of the shins, and around the middle of the century they were made movable.

Leggings and plate shoes were made for noble knights of that period.

Even before the beginning of the 16th century, loose cloaks and gambizons were worn over armor, but later they were replaced by tight-fitting clothing, which was richly decorated with silk and embroidery. In the same 14th century, a lentner began to be worn over chain mail. At the same time, the hood of the chain mail began to be made separately from the chain mail itself.

Unique tournament armor of Henry VIII - silver-plated and engraved.

At the end of the 14th century, knights began to use an iron breastplate of a semicircular shape, in which the upper part was movable; later a backrest of the same kind appeared.

They also began to protect their hands with mittens made from iron plates.

By the end of the 14th century, the chain mail aventail completely fell out of use, and the chain mail shirt now had a high collar. The first legguards emerged from the need for a more comfortable fit on a horse, when a wide extension was sewn to the edge of the plate skirt.

And at the beginning of the 15th century, the first shoulder pads appeared with a deep cutout on the right side, for the convenience of carrying a spear.

Plate armor fully formed by the 15th century, then their changes were not so significant or amenable to fashion trends.

15th century plate armor

Since 1500, grooves and corrugations have appeared on some elements of armor (except greaves).

This innovation made the armor more durable, although its weight did not change. Such armor began to be called “Maximilian armor”, in honor of Maximilian I, who loved to carry out reforms to transform weapons.

In the 16th century, Maximilian armor was actively used in tournaments and battles; it was worn to participate in festive celebrations, where it was transformed into richly decorated clothing. At that time, a knight had to have several types of armor - for tournaments, for battles and for a “ceremonial” exit - richly decorated. All together they cost incredible amounts of money, so gunsmiths tried to make the armor universal, complementing it with various accessories. During this period, chain mail, which was previously worn under armor, went out of use.

Since the beginning of the 17th century, every gentleman wore leather tights under a bib, the hem of which reached half the thigh. And only the imperial cuirassiers wore equipment that was still too heavy, reminiscent of old plate armor. But even though they were thick, they still remained useless against the increasingly widespread firearms.

At knightly tournaments of the 17th-18th centuries, armor was an integral attribute of noble dignity, and in ceremonial portraits of those times, nobles were depicted exclusively in armor.

Ceremonial portrait of Louis XIII in armor